Dialectical Reading Journal

advertisement

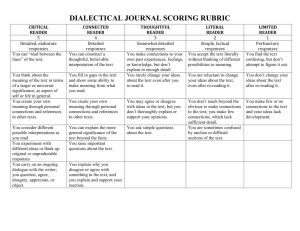

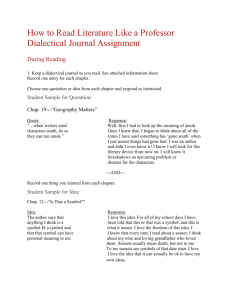

You must annotate the books you read for your summer reading assignment. Annotating in the book itself is the easiest method. If you have an aversion to writing in your books, you may use sticky notes, or you may take notes on another sheet of paper in the form of a dialectical reading journal. The directions for this type of annotation follow. What should you annotate? You should annotate anything that interests you or seems important. You should make note or write questions about ideas that confuse you. You should comment on things you find amusing or horrifying, and you should jot down any memories, ideas, or connections that are formed as you read the work. The directions for the dialectical reading journal provide additional information on the kinds of things necessary for good annotation. Dialectical Reading Journal Reading is more than simply moving your eyes back and forth across a page. Reading is more like a dialogue, a conversation between the author and the reader. When it comes to comprehension, you need to actively participate rather than inactively sit back and expect the meaning to come to you. At a personal study level, active reading means you mark significant places in the text , make marginal notes, and perhaps write in your notebook, too, recording important points or noting how the material strikes you. Although there are many ways to respond to reading one way is a dialectical reading journal. The dialectical journal is a type of double-entry note-taking system which students use while reading literature. It has two halves that “speak” to each other as in a dialogue. In the two columns students write notes that dialogue with one another, thereby developing critical reading and reflective questioning. Writing about what you read is one of the best ways to deepen your understanding while improving your writing. A few words about reading: Whether or not a piece of reading gets you excited on an emotional or intellectual level, your job is to learn how to have something to say about it (that’s part of the academic project of intellectual inquiry). When you read, you may not like the content of a particular piece, especially when its academic style is new to you. You should, however, be able to explore your reaction to a text as a way of working into it. On the other hand, you may absolutely love it and want to share with everyone what you think is so great. The one thing you can’t do is wait to be moved. Even if you feel as if you have no reaction, your brain is absorbing and processing. Keeping a journal of your reading experience can help you make visible the reaction that your brain is already engaged in. Likewise, when we come together to talk about texts, you will have your thoughts and reactions in written form to facilitate the discussion. How to talk about essays and readings Here are five generic questions guaranteed to open up almost everything you need to know about a piece of writing. They’re ambiguous because no one can stipulate the reaction you must have to a text. But you have to be willing to have some reaction that allows us to work together to enrich our understanding of the text. These questions are ways to begin doing just that. 1. What do you see in here? This is not a trick. A reader begins as an observer and works out from there. How does the text move you or interest you or annoy you? If it bores you, why? What does the writer say that is interesting? What is left unsaid and why? Does it make you think in a new direction or give you insight into something? What are some key passages or features necessary for fully understanding this piece of writing? What questions do you have? 2. What can you make it mean? Yes, most texts have a literal meaning that will resist attempts to make it mean just anything. What we do as readers is to extend what a writer leaves for us beyond that literal interpretation. In our daily lives we cannot avoid interpretation, but when reading a “finished” text, one may assume that there is only one meaning. What we should try to do is to construct new meanings from texts, to ask questions, and to explore possibilities. 3. What do you see it doing? In other words, pay attention to the work as a writer would. How is the piece constructed? Does it make surprise moves? Is it predictably competent? If you get lost, why did it happen? Where is it not holding your attention and why? Where exactly does it strain your ability to pay attention? What interests you about the writing in the text? Get at the features of the text and how those features affect you as a reader. 4. What is admirable? Simple appreciation is an essential part of being a good critical reader. When you are willing to say to the rest of us, “Look, this part is good and here is the reason,” you help teach us to see the text in a new way: the way you did. We gain from your attentiveness, and you gain by working publicly to tie the good things you see to the ways the text is effective. 5. What do you not quite understand? Reading isn’t about mastery any more than writing is. In school we learn to cover over what we don’t understand to avoid poor grades. But when you’re working through a text, you need to express your confusions, whether they’re literal, structural, or conceptual. Dialectical Journal Format Attached is a sample dialectical journal page. You may make copies of this one or create your own in a notebook. On the left side, record a passage from the text, a quote, or a phrase. Pick something you think is worthy to note. The above five questions can help you think of possibilities. On the right side, put your reactions into words. This column is the place to explore ideas, to think in writing. Finally, write a commentary that is an overall reaction to your responses, not a summary of the piece itself. Name: Date: Reading Response for: Your overall commentary on your responses will follow your journaling. Here you write a concluding comment or approximately half a page. Reread what you’ve written in the columns. What do you see? What connections can you make?