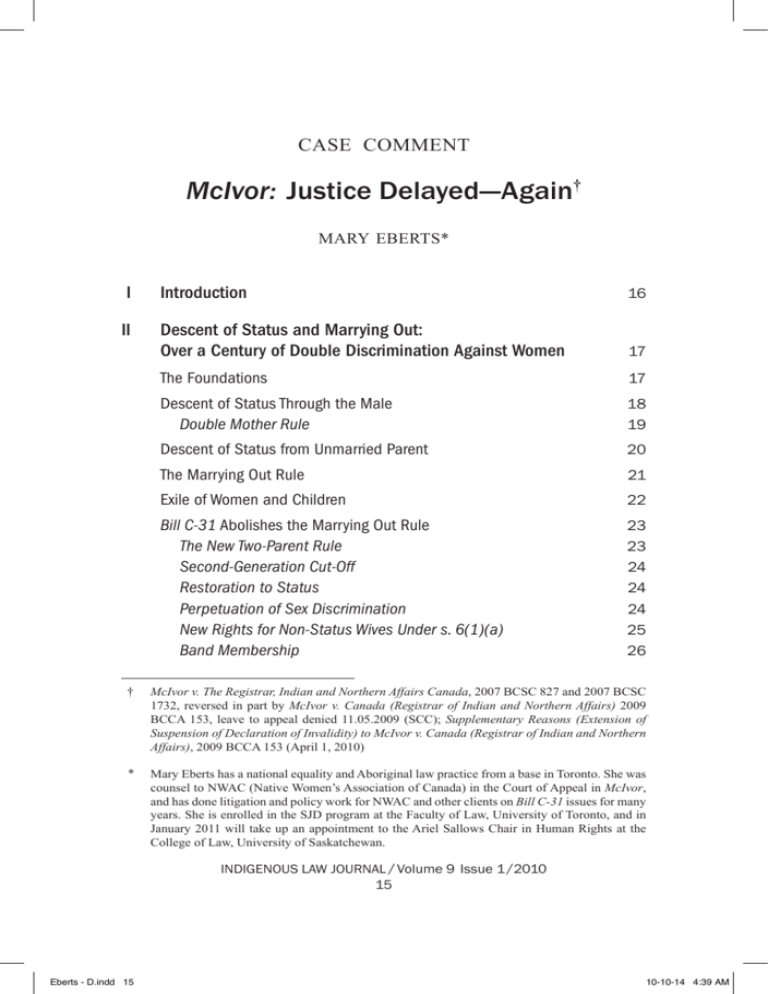

McIvor: Justice Delayed - Again

advertisement