P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

PP427-369603

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

C 2002)

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, Vol. 14, No. 3, July 2002 (°

The Child Sexual Abuser: Perceptions of College

Students and Professionals1

Daniel A. Fuselier,2 Robert L. Durham,2,3 and Sandy K. Wurtele2

College students and members of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual

Abusers (ATSA) were compared as to their beliefs and attitudes concerning perpetrators of child sexual abuse. Analyses of a 44-item inventory (assessing beliefs

about an abuser’s demographics and attitudes concerning an abuser’s cognitions

and behaviors) indicated that the groups differed on perceived demographic descriptors (e.g., students believed perpetrators to be older when they first begin

offending, more educated, and more likely to be gay than the professionals) and

behaviors (e.g., students believed that the perpetrator was more likely to use force

to gain the child’s compliance). In addition, 2 subscales (Cognitive Distortions

and Perceived Social Functioning) were identified. Compared to professionals,

students were less likely to believe perpetrators use cognitive distortions and were

more likely to believe perpetrators function at a lower interpersonal level. Results

are discussed in terms of the efforts to educate the public about the characteristics

of child sexual abusers.

KEY WORDS: child sexual abuse; attitudes; behaviors; cognitions; demographics.

The past two decades have witnessed increasing research attention to the

problem of child sexual abuse (CSA). There have been multitudes of empirical

investigations into the incidence and prevalence of CSA, along with the consequences associated with this form of abuse. Researchers have also attempted

to describe the characteristics of both victims and perpetrators. Although there

are an increasing number of studies appearing in the literature that focus on the

1 This paper is part of the first author’s thesis for the degree of Master of Arts submitted to the Department

of Psychology at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

of Colorado at Colorado Springs, Colorado.

whom correspondence should be addressed at Department of Psychology, University of Colorado

at Colorado Springs, PO Box 7150, Colorado Springs, Colorado 80907-7150; e-mail: rdurham@

brain.uccs.edu.

2 University

3 To

271

C 2002 Plenum Publishing Corporation

1079-0632/02/0700-0271/0 °

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

PP427-369603

272

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Fuselier, Durham, and Wurtele

perpetrators of CSA, our knowledge regarding these individuals is still limited.

Even more limited is our knowledge about public perceptions of perpetrators. This

study compares the perceptions that college students have of child sexual abusers

with the perceptions held by clinical practitioners in the field of sexual abuse. A

survey is used to assess student and professional perceptions and test the degree

of correspondence between the two groups.

Few studies have explored the general public’s knowledge and beliefs about

CSA perpetrators. In one study, parents who had attended an educational program

about CSA thought that 25% of CSA was committed by strangers (Berrick, 1988).

Similarly, Wurtele, Kvaternick, and Franklin (1992) found that although most parents warned their children about strangers (90%), only a few parents described

CSA perpetrators as known adults (61%), adolescents (52%), relatives (35%),

parents (22%), or siblings (19%). A survey of adult respondents living in a rural

community found that 18% of the total sample believed that a stranger was the

most likely perpetrator of CSA (Calvert & Munsie-Benson, 1999). In addition to

perceiving perpetrators as strangers, Conte and Fogarty (1989) found that over

one third of parents surveyed believed offenders were “unmarried, immature, and

socially inept” (p. 7). In Morison and Greene (1992), approximately 20% of jurors

supported the stereotyped image of an abuser as a “Dirty Old Man.” A significant

number were equally unaware that abusers are typically familiar to the victim. Seeing CSA perpetrators as social misfits, strangers, or “Dirty Old Men” appear to be

myths endorsed by the general public; other myths and stereotypes of child sexual

abusers likely exist. Identifying public perceptions of perpetrators is important for

developing public education about CSA.

This study was designed as a preliminary examination of the characteristics

of CSA perpetrators as perceived by college students and treatment professionals.

To this end, an inventory was designed to assess attitudes and opinions concerning

characteristics of abusers. It was hypothesized that students would be more likely to

see abusers conforming to the stereotypical characteristics, whereas professionals’

perceptions would reflect characteristics of actual perpetrators.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were obtained from two populations—“students” and “professionals.” The student sample was composed of 203 undergraduate students enrolled

at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs (141 females and 79 males, mean

age = 22.7 years). Students received class credit for their participation. Of these

students, 13.3% reported that they had experienced sexual abuse as a child, 33%

indicated that they knew someone who had sexually abused children, and 63%

reported that they knew someone who was abused as a child.

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

PP427-369603

Perceptions of the Child Sexual Abuser

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

273

The professional sample consisted of 144 members of the Association for

the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ATSA). Three hundred ATSA members were

randomly selected from the membership roster, and 153 surveys were returned

(51% response rate), with 144 surveys being complete. There were 86 males and

48 females (mean age = 46.6 years). Over 19% had experienced sexual abuse as

a child and, as would be expected, 89% knew someone who had sexually abused

children and 97% knew someone who was abused as a child.

Materials

The 44-item Child Sexual Abuse Survey used in this study was developed

from a review of current literature on CSA perpetrators. The instrument was divided

into three sections containing Likert-type items, semantic differential scales, and

items describing potential demographic characteristics of abusers. This survey is

available from the second author and the literature supporting the items is presented

below. In addition to these items, both students and professionals were also asked

to complete a brief demographic questionnaire.

In Section I, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed

or disagreed with each of the 22 statements. A 6-point Likert scale was employed,

where 1 = strongly disagree and 6 = strongly agree. Nine statements described

some of the cognitive distortions that molesters use to deny, minimize, justify,

and rationalize their behavior (Murphy, 1990). In several studies, child sex offenders have been found to be more likely to endorse attitudes and beliefs about

the acceptability of sexual activity with children than non–child sex offenders

(Blumenthal, Gudjonsson, & Burns, 1999; Hayashino, Wurtele, & Klebe, 1995).

Seven statements dealt with emotional/psychological characteristics of offenders, including self-control problems and insecurities about interpersonal relationships. CSA perpetrators have been described as needing to assume power and

control over others (Hilton & Mezey, 1996), as exhibiting poor impulse control,

and as using alcohol or drugs to lower their inhibitions (Groth, Hobson, & Gary,

1982; Yanagida & Ching, 1993). Other studies describe molesters as lacking social

skills and as being overly sensitive to negative evaluation (Hayashino et al., 1995;

Seidman, Marshall, Hudson, & Robertson, 1994). Three statements appraised

the extent to which offenders feel guilt or shame for their transgressions. Studies have found child sex offenders to report more feelings of guilt, remorse,

or regret than sex offenders against adults (Blumenthal et al., 1999). Finally,

three statements described offenders as having a history of childhood molestation, as being male, and as not knowing their victims. CSA perpetrators frequently report a history of childhood molestation (Becker, 1994; Overholser &

Beck, 1989), 90% or more are male (Barnett, Miller-Perrin, & Perrin, 1997), and

are rarely strangers to the child. Large-scale community surveys of adults reporting childhood histories of abuse have found 11% (Russell, 1983) and 21%

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

PP427-369603

274

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Fuselier, Durham, and Wurtele

(Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990) of female victimizations to involve

strangers.

Section II of the survey contained 11 semantic differential scales, where the

participant rated “average” abusers along several dimensions, including physical

characteristics, reputation, moral development, self-concept, interpersonal skills,

impulse control, and intelligence. Item 12 asked about the extent to which abusers

use force or violence to get the child to comply. It has been assumed that most sexual

offenses against children are nonviolent, with many experts estimating that physical violence accompanies CSA in only 20% of incidents (e.g., Timnick, 1985),

although recent research suggests that offenders are more frequently aggressive

(Becker, 1994).

Section III contained 10 questions asking about various demographic characteristics of abusers, including age, gender, race, marital status, along with socioeconomic status (SES) and educational levels. Research indicates that most CSA

perpetrators are White males, in their thirties, single, fairly well educated, and

employed (Abel, Becker, Cunningham-Rathner, Mittelman, & Rouleau, 1988). In

addition, offenders are familiar to the child in the majority of cases (Barnett et al.,

1997). However, offenders come from any racial, occupational, or socioeconomic

group (Groth, et al., 1982), diminishing the probability of there being an “average”

abuser.

Procedure

Students were tested in small groups at a campus laboratory. They were explained the nature of the study and, after giving their consent, filled out the instruments anonymously. The ATSA members were randomly selected from the membership roster (restricted to domestic members). The cover letter informed them

that they were randomly selected as representatives of professionals for the study.

RESULTS

Results of this investigation are presented in three parts. First, differences

between the two groups on perceived demographic characteristics of offenders

are presented. Second, perceptions of the dynamics of abuse are presented. Third,

differences between the two samples on shared subscales are explored.

Perceived Demographic Characteristics

Students and professionals did not differ in their assessment of the gender of

abusers. Both groups agreed that abusers were predominantly male, Professional =

83% and Students = 81%, t(339) = 1.26, ns. Nor did the groups differ significantly

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

PP427-369603

April 3, 2002

8:33

Perceptions of the Child Sexual Abuser

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

275

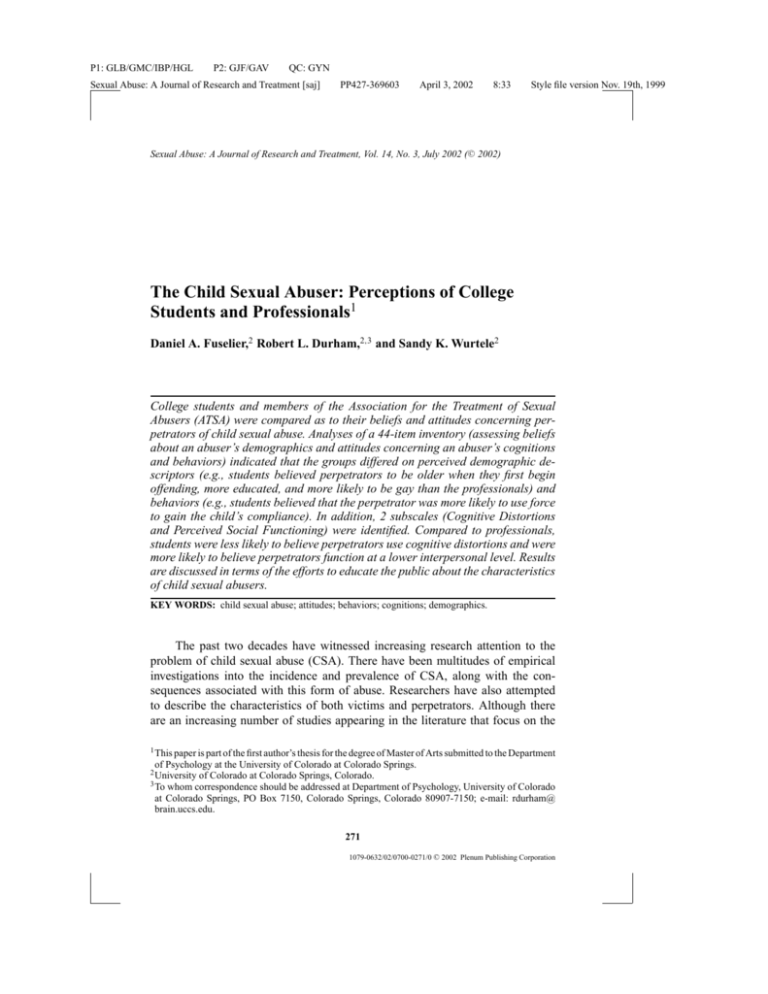

Table I. Abuser Characteristics as Perceived by Students and Professionals

Characteristic

Age (years)

Socioeconomic status (%)

Low

Middle/High

Education level (%)

Did not complete H.S.

High school graduate

Some college or higher

Marital status (%)

Single/Never married

Divorced

Married

Sexual orientation (%)

Heterosexual woman

Heterosexual man

Gay man

Relationship to child (%)

Stranger

Acquaintance

Authority figure

Family member

Parent/Parent substitute

Method used to abuse child (%)

Force/Aggression

Threats

Bribes

Other

Students

Professionals

p

19.33 (7.32)

13.24 (3.67)

.001

.001

5.0

95.0

20.5

79.5

6.4

53.5

40.1

12.8

75.2

12.0

37.8

11.9

50.2

12.1

9.1

78.8

3.6

90.3

6.2

6.8

91.7

1.5

8.38

15.61

15.15

33.47

27.39

6.53

15.78

11.79

29.93

35.97

15.3

33.0

46.3

5.4

1.4

9.7

65.3

23.6

.001

.001

.05

.01

ns

.001

.06

.001

.001

Note. Probabilities reported are from appropriate statistical procedures (Welch’s

t test and chi-square test). Because of cells with zero frequencies, categories in

the socioeconomic status and educational levels were combined.

on their perceptions of the race or ethnicity of the offender. Subjects perceived

offenders as being primarily Caucasian (83%). Other responses included African

American (1%), Asian American (1%), Native American (1%), Latin American

(1%), and other (13%).

Students and professionals did differ in their perceptions of the abuser’s age,

SES, educational level, marital status, sexual orientation, and relationship to victim. Results of these analyses are presented in Table I. Compared to professionals,

students perceived offenders to be older when they committed their first offense,

t(341) = 9.1, p < .001, as being from a higher SES level, χ 2 (1, N = 334) =

19.48, p < .001, as having completed more education, χ 2 (2, N = 335) = 31.52,

p < .001, as less likely to be married, χ 2 (2, N = 333) = 30.17, p < .001, and

more likely to be gay, χ 2 (3, N = 328) = 5.66, p = .059. Students and professionals were also compared on how they distributed the relationships abusers had

with the children they abuse. Five tests compared the two groups on the percentages they differentially assigned to the relationship categories. (The assumption

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

276

PP427-369603

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Fuselier, Durham, and Wurtele

of homogeneity of variance was not met on three of the tests; therefore Welch’s t

statistic was used in those instances.) As can be seen in Table I, the groups differed

significantly on three of the categories. Specifically, more students believed that

a larger percentage of abusers are strangers and authority figures than did professionals. In contrast, more professionals believed that a larger percentage of abusers

are parents or parent substitutes than did students.

Perceived Dynamics of Abuse

The two groups did not significantly differ in their perceptions of the number

of times an offender abuses a child. Responses included one time (1%), 2–3 times

(11%), 4–10 times (29%), 11–50 times (44%), and hundreds of times (15%),

χ 2 (4, N = 339) = 4.05, ns. Students and professionals differed in their perceptions

about the method an offender uses to make a child participate in sexual activities. As

can be seen in Table I, students were more likely than professionals to believe that

offenders use force, aggression, or threats, whereas professionals were more likely

to report that offenders use bribes, χ 2 (3, N = 347) = 63.73, p < .001. Similarly,

when asked how often perpetrators use force, students believed that perpetrators

used force or violence to get the child to comply more than professionals did,

t(345) = 6.61, p < .001. Students scored higher (M = 3.39, SD = .82) than

professionals (M = 2.83, SD = .73) on this item.

Group Differences on Subscales

Two subscales (Cognitive Distortions and Perceived Social Functioning) were

identified (see Table II). These subscales had acceptable internal consistency, with

Cronbach’s alphas of .81 and .82 respectively. The scores were summed to obtain

Table II. Items Comprising the Two Subscales

Cognitive distortions subscale

An abuser blames the child for their sexual encounter

An abuser believes that having sex with a child is a good way to teach the child about sex

An abuser believes that when a child asks about sex it means that the child wants to have sex with

the adult

An abuser believes that children enjoy having sex

An abuser believes that a child who physically resists really wants sex anyway

Perceived social functioning subscale

Abuser’s reputation

Abuser’s community standing

Abuser’s intelligence

Abuser’s commitment to job

Abuser’s sense of morals

Abuser’s mental soundness

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

PP427-369603

Perceptions of the Child Sexual Abuser

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

277

subscale scores for both groups. The two groups were then compared on each

subscale. On the Cognitive Distortions subscale, the two groups significantly differed, t(339) = 7.44, p < .001. Students (M = 17.45, SD = 5.12) were less likely

than professionals (M = 21.29, SD = 3.98) to believe that abusers use cognitive

distortions to justify or rationalize adult–child sex. On the Perceived Social Functioning subscale, students perceived abusers as functioning lower interpersonally

and occupationally (M = 24.48, SD = 6.44) than did professionals (M = 27.98,

SD = 4.99), t(339) = 5.39, p < .001.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to compare perceptions of child molesters held

by college students and treatment professionals. Results of the present investigation demonstrate that the two groups held fairly similar and accurate perceptions.

Where there were differences between the two groups, students tend to endorse

some stereotypical characteristics of molesters, whereas professionals’ perceptions

reflected characteristics of actual perpetrators.

In terms of demographic characteristics, both groups perceived abusers as

Caucasian males, which is consistent with the literature (Abel et al., 1988). Compared to professionals, students perceived offenders to be of an older age when

they first begin offending: 19.3 versus 13.2 years. Therefore, both groups appear

to be aware that sexual perpetration often has its onset during the adolescent years

(Becker, 1994; Briggs & Hawkins, 1996). Additionally, neither students nor professionals endorse the “dirty old man” myth found in other studies.

Compared to professionals, students perceived offenders as having completed

more college education and as being from a higher SES level. Students appeared

to be describing offenders as being similar to themselves in terms of academic

achievement, whereas the professionals’ lower ratings of offender education were

likely influenced by their familiarity with the typical offender’s academic achievement. Students saw offenders as less likely to be married, and more likely to be

gay men, although the majority of both groups perceived offenders as heterosexual men. In terms of victim–perpetrator relationship, students also believed that

a larger percentage of abusers are strangers and authority figures than did professionals. Encouragingly, very few students (8%) endorsed the “stranger–danger”

myth. In contrast, professionals believed that a larger percentage of abusers are

parents or parent substitutes, consistent with findings from child abuse reporting

systems and clinical programs. In general population surveys, abuse by parent

figures constituted between 6 and 16% of all cases (Berliner & Elliott, 1996), and

in clinical treatment programs, 40% of offenders functioned in the role of a parent

(Gomes-Schwartz, Horowitz, & Cardarelli, 1990). As found in other studies of the

general public (e.g., Morison & Greene, 1992), students in this study appear to

view a perpetrator as someone who is from outside the child’s family.

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

278

PP427-369603

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Fuselier, Durham, and Wurtele

In terms of typical offense characteristics, both groups agreed that only a

minority of cases involve a onetime episode, with almost three fourths of the total

sample perceiving abuse as occurring between 4 and 50 times. Indeed, multiple

abuse episodes are very common, occurring in more than half of the cases in nonclinical samples and in 75% of clinical cases (Berliner & Elliott, 1996). However,

the two groups differed in their perceptions about the method an offender uses

to make a child participate in sexual activities. As found in Morison and Greene

(1992), students were more likely than professionals to believe that offenders use

force or violence to gain victim compliance. Students appear less knowledgeable

about the subtle grooming strategies abusers use to gain access to children. Professionals are more aware of the role that bribes and enticements play in recruiting and

maintaining child victims. Offenders usually engage in a gradual process of sexualizing the relationship over time, often employing emotional coercion, offering

tangible rewards, or misusing adult authority to maintain children’s cooperation

(Berliner & Elliott, 1996). Students who believe that molestation usually involves

force may not appreciate that a serious offense has been committed when force is

not used, or they may be less likely to believe a child’s accusation of abuse in the

absence of force.

Students’ and professionals’ scores on the two subscales (Cognitive Distortions and Perceived Social Functioning) differed significantly. Students believed

that the abuser functioned at a slightly lower interpersonal level than did the professionals. Professionals saw the abuser as functioning at a higher, presumably

more “normal” level, than did the students. Similarly, students were less aware of

perpetrators’ use of cognitive distortions. Cognitive distortions related to sexual

offending are self-statements molesters use to deny, minimize, justify, and rationalize their behavior (Murphy, 1990). Not only did students perceive perpetrators

as using force or violence to initiate sexual activity, but they were less aware of the

perpetrators’ use of cognitive distortions to maintain a sexual relationship with a

child victim. Because of their frequent contact with offenders, professionals were

more aware of perpetrators’ use of these self-statements to justify their actions.

We cannot say whether the opinions expressed by this group of undergraduate students are representative of the perceptions of the general public. Indeed,

other researchers have found well-educated participants to be more knowledgeable

about CSA compared to participants with a high school education or less (Morison

& Greene, 1992). Future research needs to be directed at assessing the perceptions

of perpetrators among nonstudent populations, and also among parents, educators,

childcare workers, clergy, and others who are responsible for the welfare of children. Nor can we claim that the characteristics of perpetrators provided by ATSA

members are the characteristics of offenders in the general population. The clinicians can only describe offenders who have been caught and arrested; undetected

sexual abusers are most likely not included in their perceptions.

Results suggest that efforts to educate the public about child sexual abuse

may be working, as reflected in the accuracy of students’ perceptions of some

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

PP427-369603

April 3, 2002

Perceptions of the Child Sexual Abuser

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

279

characteristics of offenders (e.g., few students described offenders as strangers).

At the same time, educational efforts need to address some of the other characteristics of child abusers. Specifically, it is important for the general public to be

aware that perpetrators are often family members or parent substitutes who function “normally” in society. It is also important to stress that abusers often begin

offending during early adolescence, rarely use force or aggression to initiate the

sexual relationship, and often employ cognitive distortions that allow them to continue offending without feeling guilt, shame, or anxiety. Educational efforts would

hopefully serve to increase the identification and reporting of sexual abuse cases

that do not fit a stereotype.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers for

allowing us access to their membership roster, and the members themselves for

their assistance.

REFERENCES

Abel, G. G., Becker, J. V., Cunningham-Rathner, J., Mittelman, M., & Rouleau, J. L. (1988). Multiple

paraphilic diagnoses among sex offenders. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and

the Law, 16, 153–168.

Barnett, O. W., Miller-Perrin, C. L., & Perrin, R. D. (1997). Family violence across the lifespan: An

introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Becker, J. V. (1994). Offenders: Characteristics and treatment. Future of Children, 4, 176–197.

Berliner, L., & Elliott, D. M. (1996). Sexual abuse of children. In J. Briere, L. Berliner, J. A. Bulkley,

C. Jenny, & T. Reid (Eds.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (pp. 51–71). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Berrick, J. D. (1988). Parental involvement in child abuse training: What do they learn? Child Abuse

and Neglect, 12, 543–553.

Blumenthal, S., Gudjonsson, G., & Burns, J. (1999). Cognitive distortions and blame attribution in sex

offenders against adults and children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23, 129–143.

Briggs, F., & Hawkins, M. F. (1996). A comparison of the childhood experiences of convicted male

child molesters and men who were sexually abused in childhood and claimed to be nonoffenders.

Child Abuse and Neglect, 20, 221–233.

Calvert, J. F., Jr., & Munsie-Benson, M. (1999). Public opinion and knowledge about childhood sexual

abuse in a rural community. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23, 671–682.

Conte, J. R., & Fogarty, L. A. (1989). Attitudes on sexual abuse prevention programs: A national survey

of parents. (Available from J. R. Conte, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 4101

15th Avenue N. E., Seattle, WA 98195-6299).

Finkelhor, D., Hotaling, G., Lewis, I. A., & Smith, C. (1990). Sexual abuse in a national survey of

adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 14,

19–28.

Gomes-Schwartz, B., Horowitz, J. M., & Cardarelli, A. P. (1990). Child sexual abuse: The initial effects.

Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Groth, A. N., Hobson, W. F., & Gary, T. S. (1982). The child molester: Clinical observations. In J. Conte

& D. A. Shore (Eds.), Social work and child sexual abuse (pp. 129–144). New York: Haworth.

P1: GLB/GMC/IBP/HGL

P2: GJF/GAV

QC: GYN

Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment [saj]

280

PP427-369603

April 3, 2002

8:33

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Fuselier, Durham, and Wurtele

Hayashino, D. S., Wurtele, S. K., & Klebe, K. J. (1995). Child molesters: An examination of cognitive

factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10, 106–116.

Hilton, M. R., & Mezey, G. C. (1996). Victims and perpetrators of child sexual abuse. British Journal

of Psychiatry, 169, 408–415.

Morison, S., & Greene, E. (1992). Juror and expert knowledge of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and

Neglect, 16, 595–613.

Murphy, W. D. (1990). Assessment and modification of cognitive distortions in sex offenders. In

W. L. Marshall, D. R. Laws, & H. E. Barbaree (Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault (pp. 331–342).

New York: Plenum.

Overholser, J. C., & Beck, S. J. (1989). The classification of rapists and child molesters. Journal of

Offender Counseling, Services and Rehabilitation, 13, 15–25.

Russell, D. E. (1983). The incidence and prevalence of intrafamilial and extrafamilial sexual abuse of

female children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 7, 133–146.

Seidman, B. T., Marshall, W. L., Hudson, S. M., & Robertson, P. J. (1994). An examination of intimacy

and loneliness in sex offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 9, 519–534.

Timnick, L. (1985, August). 22% in survey were child abuse victims. Los Angeles Times, p. 1.

Wurtele, S. K., Kvaternick, M., & Franklin, C. F. (1992). Sexual abuse prevention for preschoolers: A

survey of parents’ behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 1, 113–128.

Yanagida, E. H., & Ching, J. W. (1993). MMPI profiles of child abusers. Journal of Clinical Psychology,

49, 569–576.