Mason, Dancy, MA, ENGL, August 2011

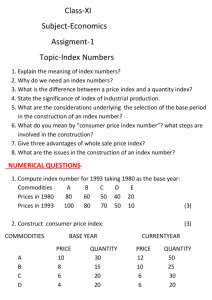

advertisement