Using Names and Terms Correctly

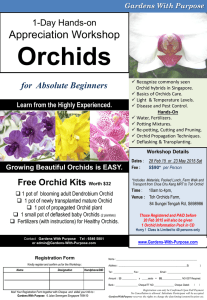

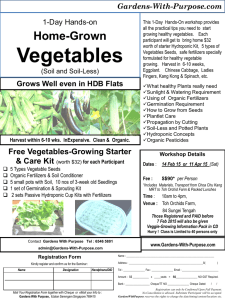

advertisement

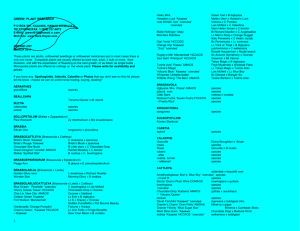

BEGINNERS HANDBOOK Using Names and Terms Correctly THE STRANGE JARGON USED BY ORCHIDISTS, the seemingly unpronounceable orchid names found in books and catalogues and the many odd terms which are not found in the average dictionary, can be a cold shower upon your enthusiasm as a novice in the hobby of orchids. If your interest isn't arrested, you may bravely flounder through a perplexing fog of half-knowledge, only to find out later that the imperfectly understood terms and guessed-at pronunciations will remain a source of uncertainty and embarrassment. It is better to become familiar with some of the word tools at once, so that you may fully understand what you read and hear later on. This second part of the Beginners' Handbook series will help you to get started on the right road from the beginning. The several questions that arise regarding orchid names are how they are pronounced, how they are used and how they are derived. With terms used in orchid culture we need to know how they are pronounced and precisely what they mean. Since there are many thousands of orchid names, we will have to content ourselves with some basic principles in orchid nomenclature, citing a few examples, but letting most of the names come gradually in subsequent chapters. The bulk of the commonly used terms will be presented here, with illustrations where possible, with lesser important terms to be introduced as their need arises. ORCHID NAMES Within the Plant Kingdom, plants having fundamental similarities are arranged together in groups called families, possibly the largest of which is the Orchid Family. Within each family, plants having a still greater degree of similarity are grouped together into genera (JEN-eh-rah; singular is genus, JEE-nuss). Finally, within each genus, plants that are practically identical except for minor individual variations are grouped together into species (SPEE-sheez; singular is also species). Therefore, every orchid plant is an individual, a member of a species, a member of a genus and a member of a family, the Orchid Family. Now, since we know it is an individual and an orchid, we need only the name of the genus and of the species to which it belongs in order to identify it. Therefore, every orchid has a scientific name consisting of two parts by which it is known, somewhat as a person might be named "John Smith," for instance. If it were an orchid name, however, it would be stated as "Smith John" for the name of the larger grouping, the genus comes before the name of the smaller group, the species. Thus, a different species in the same genus might be named "Smith Mary." Instead of such simple and familiar names, the botanical names of orchids for the most part are derived from Latin or Greek and are more formidable to pronounce. Even experts do not fully agree on pronunciation although there is a trend toward uniformity. Specific names, that is, the names of the species, are almost always derived from Latin and follow rules of Latin pronunciation. The names of the genera are usually of Latin origin, occasionally of Greek, and very rarely from some other source. Since there are over six hundred different orchid genera, it would be a disheartening task to try to memorize all these names in one indigestible gulp. Fortunately only a portion is found in orchid collections and only a fraction of these are horticulturally important. We will list a dozen of the genera you will need to know at this time: Cattleya (CAT-lee-uh) —Named in honor of Mr. William Cattley. Cymbidium (Sim-BID-ee-uhm) — From the Greek, meaning "little boat," alluding to the shape of the lip. Paphiopedilum (Paff-ee-oo-PED-ih-luhm)—From the Greek, meaning "Venus's Slipper." Vanda (VAN-duh) — From the Sanskrit name for this type of orchid. Phalaenopsis (Fal-ehn-AHP-sis) — From the Greek, meaning "moth-like." Dendrobium (Den-DROH-bee-uhm)—Of Greek origin, "tree-living." Miltonia (Mill-TOH-ni-uh)—Dedicated to Viscount Milton, a patron of horticulture. Miltoniopsis (mill-toh-ni-OP-sis) – Miltonia-like Odontoglossum (Oh-dahn-toh-GLOSS-uhm)—From the Greek for "tooth" and "tongue" in reference to the character of the lip. Laelia (LAY-lee-uh) — Possibly derived from a Roman name. Brassavola (Brah-SAH-voh-luh)—Named for an Italian botanist. Oncidium (On-SID-ee-uhm) — From the Greek, referring to a crest upon the lip. Epidendrum (Ehp-i-DEN-drum) — From the Greek, meaning "upon trees." Members of the genus Cattleya are among the most popular of orchids for this is the florists' "corsage" orchid. There are over 150 species in this genus, some of the most popular being: Cattleya mossiae (CAT-lee-uh MOSS-ee-eye) Cattleya purpurata (LAY-lee-uh purr-purr-AH-tuh) Cattleya trianae (CAT-lee-uh TRY-an-ee) Cattleya guttata (CAT-lee-uh goo-TAH-tah) Cattleya loddigesii (CAT-lee-uh loh-di-JEEZ-ee-eye) Cattleya percivaliana (CAT-lee-uh purr-si-val-ee-AH-nah) Cattleya tenebrosa (LAY-lee-uh ten-ee-BROH-suh) Cattleya bicolor (CAT-lee-uh BYE-cuh-lor) Cattleya cinnabarina (LAY-lee-uh sin-uh-bar-EE-nuh) Cattleya intermedia (CAT-lee-uh in-ter-MEE-dee-uh) Cattleya lueddemanniana (CAT-lee-uh lewd-ih-mahn-ee-AH-nah ) Cattleya schroederae (CAT-lee-uh SHROH-der-eye) Cattleya labiata (CAT-lee-uh lah-bee-AH-tuh) Cattleya warscewiczii (CAT-lee-uh war-soo-WICK-see-eye) In the genus Laelia there are also many species but only a few of major importance, some of these being: Laelia anceps (LAY-lee-uh AN-seps) Laelia speciosa (LAY-lee-uh spee-shee-OH-suh) Laelia autumnalis (LAY-lee-uh aw-tum-NAHL-iss) You will notice that in writing these orchid names, the first name (the generic name) is capitalized while the species name is not, the entire name being in italics when printed or underscored when typed or written. Up until now we have been discussing only orchid species, that is, the kinds of orchids as found in nature. However, if two different species of orchids are mated ("crossed" is the term used), the offspring are known as hybrids. Most orchid hybrids are made by orchid fanciers and are called artificial hybrids, but natural hybrids are occasionally found in the wilds. Orchid hybrids are named in a fashion similar to orchid species but in place of the specific name there is a hybrid name, not derived from Latin or Greek but rather some proper or "fancy" name, this time capitalized. The offspring of each different combination of parents receives a different name but all offspring of the same combination (even though different individuals are used) receive the same name. As an example, if a plant of Cattleya mossiae is crossed with a plant of Cattleya warscewiczii, the offspring are all called Cattleya Enid, while if Cattleya mossiae is crossed with Cattleya trianae the progeny are known by the name of Cattleya Trimos. The hybrid sign X can be used in place of the phrase "crossed with," and the parentage of a hybrid thus indicated by a formula contained in parentheses, such as Cattleya Enid (C. mossiae X C. warscewiczii). Note that the genus name, Cattleya, is abbreviated. There are many orchid genera beginning with the letter "C," so an abbreviation must be clearly understood. By custom, an abbreviation refers to the last-mentioned genus before the abbreviation. In orchids, not all hybrids are made by crossing two different species within the same genus. Bigeneric hybrids are made by crossing species from two different genera, such as Cattleya and Laelia. The offspring belong to a hybrid genus and a new name is found, usually by combining part or the entire name of each parent. Thus, Laelia X Cattleya = Laeliocattleya (Lay-lee-oh-CAT-lee-uh), and Cattleya mossiae X Laelia anceps = Laeliocattleya Daisy. Another example is Brassavola X Cattleya, a hybrid genus called Brassocattleya. When the offspring, after two or more generations of hybridizing, contain Cattleya, Laelia and Brassavola "blood" the trigeneric hybrid genus Brassolaeliocattleya results. However, most trigeneric hybrid genera have their names formed by adding "ara" (AH-ruh) to a proper name, usually a person being so honored, such as Colmanara (Miltonia X Odontoglossum X Oncidium), named in honor of Sir Jeremiah Colman. While these previous paragraphs do not exhaust the subject of orchid names, they will provide you with sufficient knowledge to guide you in the understanding of the orchid books and magazines which you will read with fervor during the coming months. However, before you plunge headlong into orchid reading let us first consider a few of the other strange words which you will need to understand. ORCHID TERMS We can, for our purposes, distinguish two groups of orchid terms, those that refer to parts of an orchid plant or flower and those that apply to equipment, materials or techniques used in orchid growing. These latter we will take up in subsequent chapters on orchid culture and the like. The terminology that concerns us now embraces the first group. Like most other plants, orchids have roots, stems, leaves and flowers. However, because orchids grow under varying conditions and in many different environments, there are many diverse forms, and the orchids have developed many highly specialized parts As a broad generalization, orchids grow under two types of situations. Some grow in soil or rich humus, as do most common plants, and are called terrestrial (terRES-tree-uhl) orchids. This type of situation is found from the tropics to the cold parts of the temperate zones. The second situation is predominantly tropical or sub-tropical, in areas of high humidity, and the orchids grow on trees, rocks, in crannies on cliffs and the like. These orchids are called epiphytic (ehp-i-FIT-tick) orchids or epiphytes (EHP-i-fights). Actually, they grow just as other plants grow but secure their water and mineral needs directly from the moisture in the air or from the rains which wash down through the trees. The bulk of the orchids grown horticulturally are epiphytes or intermediates called semi-terrestrials. However, for the most part orchids are grown in pots with some kind of a potting medium and thus appear to be terrestrial plants. It should be noted here that orchids arc not parasites, that is, they do not obtain their nourishment from the host plant upon which they live. The tree, rock or even telephone pole, simply affords a high support where the orchid plant has ready access to moving moist air and sunlight. All orchids have basal roots springing from the lowermost part of the stem. In some genera additional roots, called aerial roots, spring from nodes along the stem. The stem, itself, varies with different groups, in some instances possessing a tough fibrous base called a rhizome (RYE-zohm), while another part of the stem may be enlarged to form a false bulb known as a pseudobulb (SYOO-doh-bulb). In other orchids, the stem is jointed like bamboo while in certain genera the stem is so abbreviated as to appear to be absent. As in all plants, the leaves arise from the stem, although there are a few orchids that do not possess leaves. In orchids, leaves vary in size, form and method of folding, such characters being used to distinguish between different groups. The flowering branch or inflorescence may spring from the base of the stem, the side of the stem or the very tip of the stem and may bear from one to many hundreds of flowers. PAPHIOPEDILUM Orchid flowers are all based on a fundamental pattern of six (really three and three) outer flower parts, but within this fixed arrangement there is an almost unlimited variation, just as in the myriad forms of six-sided snowflakes. The outer three parts are the sepals (SEE-puls) and in many genera all three sepals are quite similar. In Paphiopedilum, however, the upper or dorsal (DOOR-sul) sepal is highlymodified and the other two, called lateral sepals, are more or less united into a single part called the synsepalum (sin-SEH-pal-uhm). The inner three parts are the petals, two of which are similar while the third, called the lip or labellum (lah-BELL-uhm), is highly modified and is one of the most prominent parts of the orchid flower in most genera. At the center of the orchid flower are the sex organs combined into one unique organ called the column or gynandrium (jye-NAN-dree-uhm). It is this column that is the distinguishing character of the orchid family. PAPHIOPEDILUM PAPHIOPEDILUM The column varies somewhat in shape and size in the different genera, but the basic structure is the same. The apex of the column holds the male reproductive organ called the anther (AN-ther) within which are the masses of pollen called pollinia (pahl-LIN-ee-uh). The number of pollinia varies according to genus and each pollinium is a large aggregate of pollen-grains, numbering in the many thousands. Below the anther is a soft, sticky area called the stigma (STIG-muh), part of the female apparatus which receives the pollinia upon pollination of the flower. This stigma leads into a channel in the column known as the stigmatic cavity through the base of the column into the ovary (OH-vah-ree) which, in the orchid, is beneath the rest of the flower parts within the individual flower stem or pedicel (PEHD-i-sell). The ovary contains the ovules (OH-vyools) which develop into seed after being united with the nuclei of the pollinia. Some orchids grow in a continuous manner, like a tree, extending their single stem during each growing period. These are called monopodial (moh-noh-POHdee-uhl) orchids, examples of which are Vandas and Phalaenopsis. Others, called sympodial (sim-POH-dee-uhl) orchids reach maturity and then a new shoot emerges from an eye at the base, this shoot in turn developing to maturity to repeat the process again. Cattleyas, Cymbidiums, and Paphiopedilums are examples of this type of growth. The accompanying illustrations will help to clarify the complex of terms presented here. It will do no harm, and may do much good, to read this chapter several times, referring to the illustrations as the terms are discussed. Next month the general rules of orchid culture will be presented so that the enthusiastic hobbyist will feel that he is really "getting somewhere." Meanwhile, mastery of this month's lesson will enable you to talk and listen like a professional — awfully good for your morale.