Comments to OCC_FDIC_Bank Payday_May 30 2013_FINAL

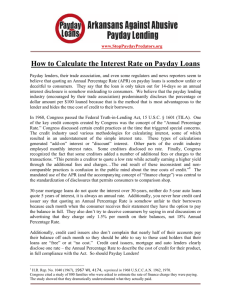

advertisement