All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education

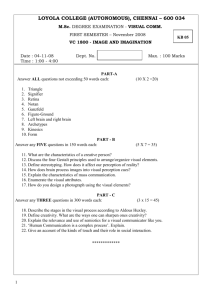

advertisement