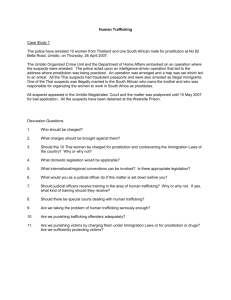

Children in Prostitution - Concerned Women for America

advertisement