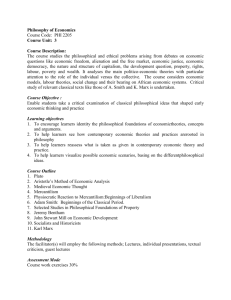

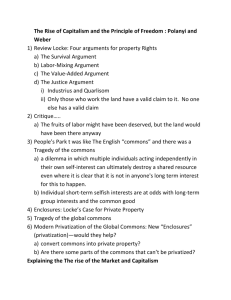

Notes on Polanyi Great Transformation

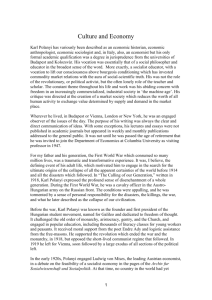

advertisement