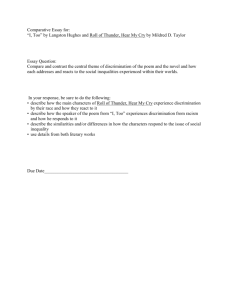

Non-discrimination Under Article 14 ECHR

advertisement