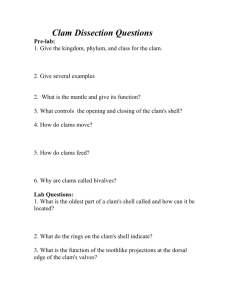

Background Information: Shellfish Basics

advertisement

What the Bay HINGES on! Background Information: Shellfish Basics Shellfish What are “shellfish” anyway? Commonly, the term shellfish refers to an aquatic invertebrate animal with a shell; especially: an edible mollusk or crustacean. So, shellfish are classified as animals, which have no backbone (invertebrate), and live in water. Usually, we refer most often to commercially important species that fit the above description as “shellfish”, although there are many more species that are inedible or not commonly harvested. There are many species of shellfish distributed all over the world, but we will focus in this guide on animals that can be found along the Atlantic Coastline, and specifically within the Barnegat Bay area. Furthermore, we will concentrate on molluscan shellfish in this guide. The term mollusk represents a group of animals with no backbone and soft, unsegmented bodies. Because the Barnegat Bay Shellfish Restoration Program focuses on Hard Clams and Oysters, the crustacean shellfish, such as shrimp and crabs, will be minimally discussed in this guide. Biological Classification Alpha taxonomy is a term used to describe the naming and organization of living things into hierarchical groups of similarities. Organisms are grouped into the following categories: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. Each of these categories are based on certain characteristics that all members share, such as the Phylum Mollusca, which have soft, unsegmented bodies, and no backbone. All mollusks also possess a mantle, a thin layer that surrounds their internal organs, and often produces a hard, calcareous outer covering, called a shell, or valve. 1 What the Bay HINGES on! All the shellfish discussed in this guide belong the Phylum Mollusca. Nearly all of these organisms belong to the Class Bivalvia, which means they are surrounded by two shells. The Whelk, our New Jersey State Shell, belongs in the Class Gastropoda, and is more similar to a snail or univalve. Commercially Important Species The molluscan shellfish that are commercially important species in New Jersey are the hard clam, soft shell clam, blue mussel, eastern oyster, surf clam, and ocean quahog. These species are regulated by the Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Bureau of Shellfisheries. Whelk are also edible, but are not commercially harvested from this geographic region. More detail on each of these species follows: Hard Clam or Quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria) – The Hard Clam is the most abundant edible shellfish in Barnegat Bay, and one of the most valuable species commercially. Hard clams have thick shells, with purple marks inside, and are slightly curved from the hinge to the front of the clam. They are found in soft mud/sand substrates. Commercial categories are named by size – top neck, little neck, cherry stone, chowder, and prepared in a variety of ways. Because of its prevalence in Barnegat Bay, this is the main species discussed in this guide.1 Oyster (Crassostrea) – These shellfish have white, black, or gray misshapen shells. Oysters attach to hard substrates, such as other shells. They are a valued food species, often served raw. Oysters were nearly completely eliminated from Barnegat Bay by over harvesting and two diseases: MSX and Dermo; Rutgers University Haskin Shellfish Laboratory on Delaware Bay has developed a disease resistant oyster. One two-inch oyster can filter up to 40 gallons of water per day. 2 What the Bay HINGES on! Soft-Shelled Clam (Mya) - These are small clams with elongated thin, white shells. They are also called steamers, or long necks, because their siphons protruding way out of the shell. They are found several inches deep in sandbars, and are often harvested recreationally. Blue Mussels (Mytilus Edulis); Mussels have elongated black shells with a silvery-blue inside lining. They are often found in the ocean, in colonies, and may grow up to three inches long. Use byssal threads to attach to rocks, piers, ropes, or other shellfish. Can filter 10-15 gallons of water per day. Bay Scallops (Aequipectin Irradians) - As the name implies, these shellfish have scalloped or ribbed shells, of varying color. Scallops swim freely using jet propulsion. They prefer to live in eel grass beds with sandy bottoms. Humans eat the adductor muscle from this species, sometimes referred to as the “eye”. Surf Clam - This clam is strongly triangular in shape, and may be 6 to 8 inches across. This is the largest clam on the Atlantic seaboard, and is found in the surf (where waves crash) area of the ocean as the name implies. The meat of this clam is used in processed seafood products such as chowders and clam strips. Ocean Quahog – This slow growing clam is often 3 to 6 inches across and may live to be 100 years old. This clam has a stronger flavor than most, and is often minced and added to other foods. Whelk – There are two kinds of whelk in this area, channeled and knob bed. The Knob bed Whelk is the state shell of New Jersey. Whelk is a predator of clams, and is eaten by humans as scungilli. 3 What the Bay HINGES on! Hard Clam Biology The hard clam will be the model organism for this guide, because of its abundance in, and importance to the Barnegat Bay. The scientific name of the Hard Clam, or Northern Quahog (pronounced Co-Hog) is Mercenaria mercenaria (Linnaeus 1758). This animal is a mollusk within the class Bivalvia, which means that its shell has two valves. The hard clam can be found naturally from Canada to Florida along the Atlantic east coast, and is an important commercial species. The full classification of the hard clam follows: Kingdom: Anamalia Phylum: Mollusca Class: Bivalvia Subclass: Lamellibranchiata Order: Heterodonta Family: Veneruidae Genus: Mercenaria Species: Mercenaria A simplistic model of the hard clam life cycle is illustrated below. The eggs (A) of M. mercenaria are buoyant and float with the currents. Fertilization is external in clams, and each female can produce millions of eggs during a spawn. This process is controlled by water temperature, has been observed between 24-26°C (75-79 °F) in the Barnegat Bay area. As larvae develop in the planktonic stage (B), many are consumed by predators. They continue to develop into swimming trochophore larvae (C) and feed on phytoplankton drifting within the water. The trochophore will develop into a veliger (D) that will develop a foot and begin to crawl on the bottom sediment. In the veliger-state the clam will swim or crawl searching for suitable bottom habitat. Hard clams that survive to settlement-stage (E) will locate on the bottom, attaching themselves to sand grains with byssal threads. At this time they develop siphons and the shell develops ridges. 4 What the Bay HINGES on! Simplified clam life cycle. Adapted from Rice 1992. They will eventually burrow into the sediment and remain there, living for over 50 years if conditions are favorable. Every year, the clam adds a layer to its shell in order to contain its growth. By observing the pattern of ridges on the shell, clams can then be aged, just like trees. Predation, sediment suitability, water quality and contaminant levels influence survivorship of clams. Poor water quality conditions may retard growth and impact clam survivorship and can increase the chances of predation on the early life stages of hard clams. 5 What the Bay HINGES on! Example of a shell cross-section, illustrating growth lines. Adapted from Rice 1992. Feeding The hard clam gathers food by taking in water from its surroundings via an incurrent siphon (Figure 2). Water and particulate matter, sand, silt and planktonic food all pass over the gills of the clam. The mucous coating of the gills traps the suspended materials in the water. Cilia on the outer wall of the gills are used to pass trapped particles to labial palps where food and other particles are separated. The food is passed onto the mouth and to the stomach. There is a digestive organ called the Crystalline style, which contains digestive enzymes and help grind food, such as silicon diatom shells. The unused particulate matter along with some missed food items are recycled to the mantle and carried toward the siphon. When enough waste is collected the clam contracts the adductor muscle, forcibly ejecting water that contains waste from the incurrent siphon (Kellogg 1903). These wastes are deposited as pseudofeces outside the shell. 6 What the Bay HINGES on! Model of the interior structures of the hard clam. reprinted by Rutgers Cooperative Extension from the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Oyster Biology The eastern oyster is similar to the hard clam in many respects. The primary differences are in the shape and texture of its shell. The fertilization, growth, and development are similar as well. Oysters prefer to set on hard surfaces, such as other shell, while clams like to dig themselves into soft sandy bottoms. Oysters are no longer a primary commercial harvest in the Barnegat Bay area, although Monmouth and Ocean counties were historically the sites of large, rich oyster beds. 7