United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Cocoa

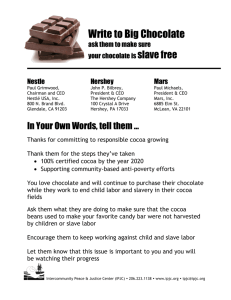

advertisement