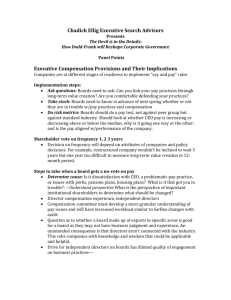

Taking Shareholder Rights Seriously

advertisement