The Impact of Shintoism on Noh Theatre

advertisement

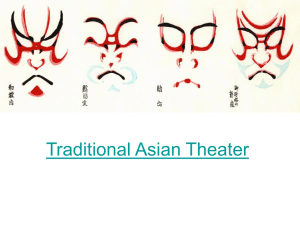

The Impact of Shintoism on Noh Theatre In Japan one of the most ancient forms of theatre is called Noh alias Nohgaku which is the oldest surviving form of Japanese Theatre. It includes music, dance and song to communicate religious messages. This classical lyric drama was created during the latter half of the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and the early part of the Muromachi period (1333-1573).1 Noh is highly stylized, masked, song and danced drama, in which beauty of voice and movement are the highest goals. Comic vignettes called Kyogen, provide the comic relief between the heavier Noh plays. These two forms have developed side by side through the centuries and are collectively referred to as Nohgaku.2 Noh is a composite art based on the three elements of song, dance and drama. Of the three, the dramatic element is the least important3. Noh should always be considered as an organized, omnibus art.4This was an aristocratic form of amusement, formal, restrained and soon static. Although it greatly influenced the other forms of native theatre, it remained primarily the theatre of the intellectual and the well to do.5 Noh is written with a Chinese character meaning „to be able‟. It signified „talent‟ hence „an exhibition of talent‟ or „performance‟.6 The development of the Noh drama can be divided into five main periods: 7 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Pre-history, the time of old legends; The Nara period (710-794) and the Heian period (794-1192) The Kamakura period(1192-1333) The Muromachi period(1333-1573) The Edo period(1600-1868) During these five main periods, Noh was influenced by various contemporary arts, such as Kagura, Bugaku, Gagaku, Waka and Renga poems, which had very formal defined structures. Origin: Noh‟s first origins have not yet been traced, although an immense amount of time and labour has been spent by academics and art historians an investigating its beginnings. Noh have gone through many stages of development over the centuries. Ze’ami Motokiyo-founder of Noh, wrote Fushikaden-Teachings 1 on style and the flower, discussing the elements of Noh origin. In the introduction, he has discussed how he thought about Noh‟s origin. “Some say that the Noh owes its origin to the country of the Buddha. Others say that it dates from the age of gods. In either case, its origin is so remote that it is impossible to imitate the original performance as it was. Here in our country, the Noh plays which people nowadays enjoy have their origin in the 66 pieces of public entertainments given by Hata-No-Kokatsu in the reign of Empress Suiko. Prince Shotoku had ordered him to give them partly to pray for peace and prosperity of the whole country and partly to give pleasure to people. He called them the sarugaku. ”8 He claimed the origin of Noh was enacted in the episode of the celestial rocky cave in the Age of the Gods. “The Noh is said to date from the age of gods. When the sungoddess concealed herself in the Celestial Rocky Cave, utter darkness reigned over the whole country. All the gods and goddesses held a meeting on Mt.Kagu in Heaven to talk about how to calm her anger. Then they played sacred music and performed comic dances. Among the rest, a goddess whose name was Ama-nouzume-no Mikoko stepped fortht, sang and danced vigorously.”9 In the same essay, the chapter 4, The History of the Noh, Zeami also suggests a possible Indian origin for sarugaku10. The hypothesis is that sarugaku had an Indian origin appear to be purely Zeami‟s own invention; certainly there are no other known sources for it.11 It is generally supposed that Noh originated from another form of entertainment. It was called sangaku, when it first came to Japan from China in the seventh century. The theatrical sangaku became more and more popular. The main sangaku repertoire in Japan consisted of mimes12. The rise of the Samurai brought Dengaku the rural folk drama, into the limelight. It was performed in order to ensure that there would be a good crop, or in order to thank the gods for a good harvest.13In the Kamakura period dengaku and sangaku (by then called sarugaku) had a strong mutual influence on each other. Sarugaku has benefitted by becoming more involved in religious ritual. In order to performs its religious role sarugaku developed in complexity, and came to include two quite different forms of drama. One was musical drama based 2 on serious themes portraying of legendary, heroes and historical events (by then called Noh).The other was comedy, which later developed in Kyogen. Okina was the most important play in sarugaku. It was thought to have been the portrayal of a dramatised Buddhist ritual. Ze’ami regarded Okina as the archetype on Noh dancing and singing,14 At the end of the Kamakura period both dengaku and sarugaku became much more dramatic15. During this time two great leading actors, Kan’ami and Ze’ami took a Sarugaku Noh and they did their best to develop it.16 History During the Muromachi period, Sarugaku Noh and Dengaku Noh almost reached their peak of perfection as performing arts17. In these periods there were many celebrated actors in both fields18. They encouraged each other in further developing Noh art19. The Yamato-sarugaku had four troupes. 1. Yukiza troupe (The troupe which later became known as Kanze school) 2. Enmai or Takeda troupe (The troupe which later became known as Komparu school) 3. Takado troupe (The troupe which later became known as Kongo school) 4. Tohi troupe (The troupe which later became known as Hosho school) These four, were called major troupes20. Kan’ami 21 is the founder of the Yukiza. Though it is called Yukiza, it was often known by his own name, Kanze-za. Kan’ami’s remarkable acting attracted much attention and his troupe soon shifted, first to the centre of Nara and finally to Kyoto22. Ze’ami and his troupe evidently enjoyed the continuing patronage of Yoshimitsu until his death in 1408.But Ashikaga‟s successor, Yoshimitsu’s eldest son Yoshinochi (1386-1428) did not care at all for sarugaku or for Ze’ami. He admired Zo’ami, a dengaku actor23. This change in power put the master of Noh in a new situation, forced him indeed into facing the possible decline of the Noh theatre. 3 In 1433, Ze’ami’s older son Motomasa died. There is some suggestion that he was murdered by order of Shogun Yoshinori. Ze’ami‟s second son Juro was too young to succeed to the leadership of the troupe. On’ami (13981467) was officially appointed head of Ze’ami‟s family troupe by the Shogun24. Ze’ami did insist on passing his treatises on to his gifted son-inlow Komparu Zenchiku (1405-1468). He refused to give them to On’ami. Komparu Zenchiku himself became a playwright and a theoretician of the Noh. 25. In the beginning, there were four main troupes mentioned earlier. Later they were joined by an additional school, which was called Kita. It was founded by Kita Shichidayu who had been a leading actor in the Kongo school. The Kita School is generally considered a branch of Komparu School26. All the works on Noh by Ze’ami were written as secret books and preserved as such for many long years. Fushikaden (Teachings on style and the Flower), the main text of which is thought to have been completed around 1402, when Ze’ami was forty, gives a through account of Ze’ami’s understanding of the art from his father Kan’ami. From the beginning of its history, Noh plays have always been written, composed and choreographed by the actors themselves.27The last major author, Kojiro of the Kanze troupe, died in 151628.There are 256 plays in the current repertory. Kan’ami has contributed ten, and Ze’ami possibly 126. There is some doubt about the authorship of twelve of them29. The principal figure in the development of the Noh was Ze’ami30. When it comes to the matter of play writing, Ze’ami was far superior to Kan’ami, not only in the number but in the quality of the works he produced. 31 Ze’ami refined the Noh and made it gracefully beautiful, attaching importance to chanting and dancing. He was a great dramatist, actor and theorist, which strikes us with admiration. Contents The plots of Noh plays are drawn from a variety of Japanese and foreign sources, mythical or legendary, fantastic, historical or contemporary, from the earliest times down to the Muromachi period (1392-1572);or inspired by Japanese and Chinese classical poems from the numerous early anthologies. Principal among the former sources are the lse Monogatari (9thcentury), and the Yamato Monogatari (10th century), the Genji Monogatari (11th century), the Heike 4 Monogatari (13th century), the Kojiki, and the Nihon Shoki (both8th century; used mostly in the Waki Noh) and the collection of Indian as well as Chinese and Japanese tales and legends known as the Konjaku Monogatari (12th century).32 Plots that are taken from the tales and legends of China and India, are called Karagoto33. Here the main characters may be a human being, an animal, or a mythological creature from a foreign land34. Noh was performed in ceremonies asking the gods to send rain, when the country was hit by drought, and in thanks giving ceremonies when the rain had come35. Okina was a most important one among Noh plays 36.Besides that Okina had always been performed on religious occasions at temples and shrines. Noh plays are generally divided into five groups, according to their subjects and central characters.37 1. Waki Noh or Kami Noh (god plays) because the hero is either a god or goddess; 2. Shura Noh (Ashura plays), whose hero is a famous medieval warrior. 3. Kazura Noh (female wig plays) essentially lyrical in character in which the protagonist is a well born lady. 4. Kurui Noh plays about loons. 5. Kiri Noh plays about demons, monsters and similar imaginary beings. First group god (Waki Noh) plays are of the two scene variety. The shite, in the first scene tells a story or recites poetry concerning the origin of a temple or shrine. After the interval, he appears in the second scene as the god of the temple or shrines described in the first scene and perform a felicitous dance. The shite is a god who praises the peace and prosperity of the land performs a dance in celebration. The plays which belong to this group were written in a simple form with very simple plots based on legend and mythology. Takasago, Tamura, Yumiya hata, Kamo and Miwa are in this first group. Takasago is generally regarded as one of the best examples of this type.38 Ashura Noh plays are also called Shura Noh39 because the central figure of the play is usually a warrior who fell in battle. Shura was a war loving evil god in Brahmanism, and the protector of religion in Buddhism. The suffering of a warrior in hell and his salvation from it are the theme of these plays. Many plays were written based on Heike Monogatari, which described the downfall of the Heike or Taira family who were defeated by the Genji family40. Among Noh plays, 5 certainly the best master pieces are the warrior- ghost plays41. Atsumori, Yashima, Sanemori, Utoh, Tamura, and Kiyotsune are in this second group. The third group of plays are called Kazura-Noh42. Kazura, in Japanese, means a wig. The main characters of the plays of this group are almost all women, and to perform these roles the actors have to wear wigs. Many woman plays 43are based on stories from the classics of court literature, such as Thinji or „the tales of Ise’. Toboku, Hagoromo, Kiritsubata and Eguchi are in this third group.44 The fourth group of plays are called Kurui Noh, lunatic pieces, monogurui Noh. Kurui literally means Madness. These plays are also generally placed in Ze’amis‟ fourth group Aisho, because they include human tragedy. There are many different kinds of main characters; old people, blind men, warriors, women, and spirits of the living and ghosts of the dead-so the plays in this are also called Zatsu, or miscellaneous Noh. In general it can be said that the plays in this group are more dramatic than any others.45 Sumidagawa and Hanagatami belong to mad woman pieces. This group can be further divided into five groups, according to the cause of the disturbances suffered by the main characters. The first of them is Fukyo, love of the poetical. The main characters in this subordinate group have an excessive love of the beauty of the nature. Kagetsu and Miidera are good example of the group. In the second subordinate group, madness caused by unrequited love is the theme. Sumidagawa is the good example for this group. This play has a tragic ending.46 In the third subordinate group, the theme is that of madness caused by supernatural possession of a human, Makiginu is good example of this group. Feigned madness is the theme in the fourth subordinate group. Characters in this group pretend to be mad in order to achieve their objectives. Hanagatami is the best example of it. The fifth subordinate group concerns genuine madness which is the cause of the sufferings of the characters in this group. The play, Semimaru is good example of it. The fifth group of plays are called kiri Noh (cut, end), tome Noh (stop), Kichiku Noh (demon, beast), Zatsu Noh (Miscellaneous). The main character 6 is often non-human; it can be a demon, an evil spirit, an animal or an imaginary creature. A demon in Noh is a symbol of evil or human fear. There are two types of demon.47 One has human feelings and thoughts. The other one is a nonhuman demon. Among the animal characters, there are a fox, a lion, a heron, a spider, and a nue which is a mixture of several animals48. The plays, Nomory, Tsuchigumo, Momijigari and Funabenkei49 belong to this category. Here plays have been classified according to the subjects and characters; genzai Noh, or realistic Noh, in which the characters are real people, and the type founded by Ze’ami called mugen Noh, „dream Noh‟ whose characters are ghosts and spirits from the other world.51 50 Noh was highly influenced by Shintoism and Buddhism. It can be seen not only Ze’ami‟s Noh plays, but also his treatises, which were written about Noh theories. Great Buddhist temples employed professional players to perform at festivals and ceremonies, and largely as a result of this, the humorous plays came to be displaced by others of a more serious nature. Many of these later plays were designed to explain the significance of religious rites or to depict Buddhist legend for the simple people. Characters Noh does not require a large number of performers. Actually, the concentrated atmosphere is produced most effectively by a single performer in a single, simple, refined dance. However, at least one more actor is necessary to provide a motive for the dance. The central characters of the Noh drama are supernatural beings (gods, devils, tengu, spirits of the dead etc.) or figures from the history of Japan (famous men or women of the Heian period, celebrated warriors of the Heike monogatari etc). There are few actors on stage in a Noh play. Usually there is the protagonist or hero (the Shite) and the deuterogamist (Waki), who provides the stimulus for the Shite‟s internal drama. The Shite appears first as a human being and then as a ghost52. The principal actor, almost invariable masked, is the Shite. In a sense, he is the only actor. Shite is related to the verb suru, „to do‟ and the Shite is the actor in the literal sense of the world, the doer, the agent. 53 He holds the key role, and it is by his performance that the play stands or falls. 54 Those who assist him in the main role are known a shite-tsure and wear masks only when impersonating 7 female characters. These characters, together with the chorus and stage assistants, belong to the same school. The actor who plays the secondary part comes from a different school and is known as the Waki; his assistants are Waki-tsure and are never masked55. Once the Waki has introduced himself and asked the questions which prompt the shite story, his job is over.56 Waki roles fall into three distinct categories. Ministers (daijin-waki) including those on a mission for the Emperor and those in charge of important temples and shrines Priests (so-waki) including all ranks and religious sects. The waki is always a human male who is alive at the time of the actions of the play. He never represents a ghost, a demon, a god, or a woman. The Waki is the representative of the audience. Actually waki is the coordinator of the play57. The waki’s costume provides sufficient identification for his role. So his face is left bare, with no mask or make up. The tsure is a character who accompanies the main character, either as shite-tsure or waki-tsure. The tomo is a companion, an even smaller role than the tsure. He wears masks only when playing female roles. Kokata means literary „child actor‟ and it indicates the type of role played by young boys; around the age of ten. It is also natural that the roles of children should be acted by young actors. But there are also several adult roles which are performed by them in Noh Kokata appear most often in the mad woman plays. Many times persons of very high rank, such as Emperor, are played by kokata. In Funa-Benkei the great warrior yoshitsune, is played by the kokata. The kyogen group has two functions in Noh. First, its members perform the comedies known as kyogen which are presented between two Noh plays. Second one or more kyogen players usually appear within a Noh play, itself, as will be seen from the list of characters. Stage Noh stage is made completely of unfinished Hinoki, a Japanese cypress, and the stage has almost no ornamentation. The term Noh stage is used to refer to the stage, bridge and mirror room, and the word stage to refer collectively to the square area of the main stage, the side stage and the rear stage58. The main stage 8 is three-dimensional solid space formed by a roof and four pillars. The side stage is a space with a railing on two sides. The special word for the passage way, between the main stage and the mirror room is the bridge; called hashigakari. The bridge is about two meters wide and usually about ten meters long, joins the stage at an oblique angle, connecting it with the mirror room (kagaminoma).The upstage part of the fan boards, called the kyogenza or ai-za, where the Ai-kyogen sits waiting to perform in Noh. The mirror room is sometimes also called the curtain room. It is an extension of the dressing room and also the beginning and ending point of both the acting and the actor‟s magical transformation.59The place that is generally occupied by the audience has a special name in Noh Kensho- the seeing place. The dressing room in a Noh theatre is normally plain tatami mattered with sliding walls. Properly there should be arrow of, such rooms, the one closet to the stage for the shite and attendants, the next for the waki, the next for the instrumentalists, and the next for Kyogen performers. Along the front of the entire structure, at auditorium floor level, is a strip of pebbles, one meter wide. In front of the bridge in this area are placed equidistantly, three pine trees. Upstage of the bridge, which is railed on the both sides, are two pine trees. A stylized pine is painted on the back wall of the rear stage. This wall contains a one meter high sliding door (kirido), the only entrance to the stage other than from the bridge. The entire structure is built of polished Japanese cypress. At the front of the main stage are three steps (kizahashi), once used by the actor moving into the audience to be congratulated by a lord. The auditorium usually seats four hundred or five hundred. The use of the stage is fixed by Tradition. The three or four musicians (hayashikata) enter from the bridge, sit on the line between main and rear stage. Stage assistants (Koken) enter through the low stage-left door and sit in the upstage right corner of the rear stage. Six or eight members of the chorus (jiutai) enter through the same door and sit on the stage. Five pillars support the roof over main and rear stage. Upstage at the point where bridge and rear stage join is the down stage of it is the principal actor‟s pillar (shite bashira) because beside it the principal actor (shite) stops after his entrance on the bridge. At the down-stage right corner of the main stage is the “eye-fixing” pillar (metsukebashira). Opposite 9 it at stage left is the waki-bashira, the pillar of the subordinate actor. Upstage of it is the “flute” pillar (fue-bashira). The chorus60 and the „choral music‟ of Noh are called jiutai or ground chant. This consists of six to twelve person in ordinary native dress seated in two rows at the side of stage. Their sole function is to sing an actor‟s words for him61. They enter by a side door before the play begin and remain seated until it is over. A Noh play uses, three or four musicians, each playing a different instrument. These are the flute, a small drum (kotsuzumi) held on the right shoulder and struck with hand; a slightly large drum (otsuzumi) held on the left hip and also struck with the hand; and in certain plays, a big drum (taiko) which is set up on a low stand and played with two drumsticks. The four instrumental musicians come on stage61a before all the other performers and play the entire music62. The instrumental music of Noh63 is usually called hayashi. It is sometimes called No-bayashi to distinguish it from the hayashi of kabuki-style singing, festival music and like. Three kinds of properties are used on the bare stage of Noh. They are stage props (tsukurimono) set to manipulate the space; small props (ko-dogu) held or worn by the actor; and multi-purpose props (tayo-dogu)64. All stage properties in Noh is simple constructions huts, boats and carts of bamboo, cloth and similar materials. They are carried on and off the stage by attendants as necessary. In contrast to the set props, which are assembled for a single performance, the various small personal properties are, polished art objects and are made to be used many times. There are hand-held props like the folding fan65. All performers are on the same level on the stage, and the beauty of Noh66 is created by a delicate balance of the art of the performers67. Shintoism Shinto or Shintoism was the primitive religion of Japan, before introducing of Buddhism. This is a very simple religion which gives one command, the necessity of being loyal to one‟s ancestors. The only deity recognized in higher Shintoism is the spiritualized human mind. 10 Shinto gives divine status equally to forces of nature, to animals or to famous people. These divinities are called kamis in Japanese. The name Shinto, however, comes from two Chinese words SHIN, meaning „good spirits, „and TAO, meaning „the way‟. So Shinto is literally „the way of the gods‟. Shinto is based on man‟s response to his natural and human surroundings68. There are no images, no sacred books and no commandments. It was originally a way of thinking, a way of looking at life. As a religion it is concerned with a verity of gods-the spirits of trees, animals, and mountains, the principles of love, justice, and order, and the god-like ancestors, heroes, and Emperors. Shinto has no supreme God and heaven, and unlike Chinese beliefs, it is not divinity but the place where the gods (kamis) live69. Prayers are made to the gods (kami) on various occasions for rain, good crops, and the coronation of the Emperors etc. Shinto approves of the representation of God in the material70.Having said that, in Shinto thought too there is an insistence that God is spiritual: the God (kami) is the power in the nature, such as mountains, the trees, the sun and not these objects themselves71.Today, the practice of Shinto does not imply any particular belief. The Japanese retain very little superstitious beliefs in the Gods (Kamis) and they do not seek any rational justification for Shinto72. Thousands of years ago, Shinto began as a religion centred about nature; and ever since it has been closely connected with the natural world. It was a combination of nature worship and animism, a belief that everything is inhabited by a soul. It gives life or activity to substances. The chief heavenly deity is Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess. To have unity with the Gods (kami), a person must have a bright, pure correct heart. If a man does not have these qualities, he is in disfavour with the Gods (kami). Shinto is the fundamental connection between the power and beauty of nature (the land) and the Japanese people. It is the manifestation of a path to understanding the institution of divine power73.Shintoists love the sun; thus they worship the Sun Goddess. The Japanese sing, dance, laugh, and clap at the sun to express their joy and gratitude. The sun provides light and warmth, and causes the rice to grow. Without the sun, all Shintoists believe they would die and go to the hell. The sun also signifies beauty, which is one of the main concepts of Shinto. Anything that has beauty beyond the power of man is considered to be the greatest kami74. Gods (Kami) are generally worshiped at shrines (jinja). Worshipers will pass under a sacred arch (torii) which helps demarcate the sacred area of the shrine. The ends of the upper crosspiece of the gate curve upward to signal 11 communication with the gods. The torii always marks a sacred place. As a symbol, the torii marks off the earthly world from the kami world; the world of everyday life is separate from the spiritual world75.Shinto has no real founder, no written scriptures, no body of religious law, and only a very simply organized priesthood 76. Most Japanese people follow both Shintoism and Buddhism. The two religions share a basic optimism about human nature, and for the world. Within Shinto, the Buddha was viewed as another kami (nature deity). Amaterasu, for example, was identified with the cosmic Buddha Vairocan Meanwhile; Buddhism in Japan regarded the kami as being manifestations of various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas77. Ancestors are deeply revered and worshiped. All of humanity is regarded as kami‟s child. Thus all of human life and human nature is sacred. Followers revere mushi, the god‟s (kami‟s) creative and harmonizing powers78. There are so many Shinto shrines; among them, some Noh scripts were based on Heian Jingu (Kyoto), The Ise Jingu, Izumo Taisha, Kasuga shrine, Osaki Hachiman shrine, and Usa Hachiman shrine. They were very famous, when the Noh scripts were written79. The Influence of Shintoism to Noh Theatre Several Noh stories were composing, based on Shinto deities, and Shinto shrines. For example, Hanjo, which describes love affair, can be discussed; how far Shinto was affected to the theatre of Noh80. In this story, Yujo, a woman, who is skilful at dance and music and entertains guests at parties. Her name was Hanago. One day she has met a man named Yoshida-no Shosho lodged at the inn on his way to the eastern provinces. He and Hanago fell in love and exchanged fans before his departure as the symbol of his promise for the future. Since then, Hanago has spent days only looking at the fan and thinking of Shosho. Since she stopped serving at banquets, the mistress of the inn at Nogami feels disgusted at Hanago who is now nicknamed Hanjo. Finally, Hanago is expelled from the inn81. On his way back from the eastern provinces, Shosho visits the inn at Nogami again. He is disappointed upon knowing that Hanago does not live there anymore81. Shosho with broken heart goes back to Kyoto and visits Shimogamo shrine to pray82. At the shrine Hanago appears by accident83. Though Hanago tries to prove the fan that she got from him, at the beginning Shosho did not believe. She shed tears in distress. Shosho was watching the dancing; Hanago pays attention to 12 her fan and asks her to show it. Later, Shosho and Hanago see each other‟s fans and recognize that they are the lovers they looked for. They are pleased by the reunion84.This drama was written by prominent playwright Kanze Ze’ami Motokiyo. Different from other stories of mad women, which describe the separation from a child or a spouse, this drama expresses sorrow, loneliness, a pure heart, and finally a joy of reunion of woman who has been distantly separated from her lover. Various emotions of woman in love are described. This is one of the highlights of Noh drama. The Noh drama, Funabenkei (Benkei in a Boat) is also based on Shinto deities and prayers85. However; dramatist did not allow the images of Shinto, to be gone up. Here Benkei rubs his Buddhist prayer beads and devotedly prays to the five great fierce deities accept his prayer, at dawn the ghosts of the Heike clan are subdued and disappear below the horizon. The drama entitled Chikubashima (Chikuba-Island) was composed by the playwright completely based on Shinto concepts; it is clear when we describe the contents of that drama in deep. A retainer of Emperor Daigo goes to Lake Biwa in order to pray at the shrine of Benzaiten (sarasvati) on Chikuba- Island. The retainer takes passage in the fishing boat of an old fisherman with a young woman whom he met on the show, sailing for the island in the lake. The old fisherman leads the retainer to the shrine. The retainer asks the fisherman whether the landing of women on the island is barred. The two then respond that this island does not prohibit women since it enshrines Benzaiten, who embodies feminists. They narrate the origin of the island for the retainer. At the end, the woman reveals that she is not a human and easily enters the shrine. The old man also reveals that he is the spirit of Lake Biwa and then disappears. During the time the retainer spends at the shrine, he is allowed see the treasure of the shrine by a Shinto priest, when the hall of the rumbles with the glowing vision of Benzaiten. Eventually, around the time when the moon serenely and clearly shines over the lake, a dragon deity appears from within the lake. The dragon deity offers precious gems to the retainer and forms the figure of blessing. She sometimes turns into a maiden from the celestial world to oblige the living creatures by making their wishes come true. Sometimes, he disguises as a dragon deity splashes himself in the waves of the lake and jumps into the Dragon King‟s Palace. Benzaiten, alias, Sarasvati shrine had been established around the fifth century. Sarasvati a divinity closely related to water. This Noh drama was completely based on the concepts of Shintoism; it developed an invigorative divine story in the mild. Even Ze’ami also when he wrote some Noh dramas, he mixed 13 doctrines of Buddhism and concepts of Shintoism together. It can clearly be seen the drama, called Kiyotsune. In the drama, Kiyotsune‟s wife returns her husband‟s hair to Usa Hachimangu shrine because holding the remembrance increases her grief. When she hopes to see him at least in her dreams, the spirit of Kiyotsune in armour appears in her dream, and the lovers who never are able to meet in this life meet in this way. Although they are happy upon their reunion, the wife blames her husband who broke the promise of reunion, and the husband blames his wife‟s heartlessness as she returns his hair to the shrine. Shinto concepts have been encountered to some Noh dramas; for example, Kanawa (Iron Trivet)86, could be mentioned one of them. It‟s contents are cultivated, mainly based on Shinto doctrines. One night, a low-ranking Shinto priest serving Kibune shrine receives a divine revelation in his dreams. The oracle says that he should give a divine message to a woman from Kyoto who visits the shrine for worship around two o„clock in the morning. In the wee hours, the woman appears at the shrine. She has walked a long distance to Kibune shrine every night to curse her former husband because she cannot forgive him for abandoning her and taking a new wife. The priest gives the woman a divine oracle, which says that if she puts on a red kimono, spreads red powder on her face, puts an iron trivet on her head; which burns with three flames‟ and holds rage in her mind; she will be able to turn into a demon as she wishes. While communicating the divine message and exchanging words with the woman, the priest begin to be frightened and run away. As soon as the woman swears to follow the oracle, her countenance changes, her hair stands an end, and thunder rumbles. The woman leaves the words of curse to let her former husband pay for her bitterness and runs away in the thunderstorm. At the end of the story, responding to the request of the man, Seimei sets up an altar at the man‟s house, places human-size dolls which represent the couple to transfer the curse into the doll, and starts exorcising the evil spirit87. This drama expresses the horror of the resentment and jealousy of woman through the evil figure of a demon. This is also a piece to express magic power, which beats off the curse imposed through Ushi-no-toki Mairi, which is the style of worship of visiting the shrine around 2 a.m. every night. Kazuraki88 Noh play also composed mixed with Buddhist concepts and doctrines of Shintoism. In this drama, Yamabushi means a man who devotes himself to the ascetic training of Shugendo, which is a religious belief derived from 14 Buddhism and Shintoism whose aim is to acquire supernatural powers through strenuous ascetic training in particular mountains in order to, relieve all living creatures of their sufferings. Among Noh dramas, Takasago89, one of the masterpieces of Zhugen Noh (Noh for celebration), has been widely appreciated since the Muromachi era. In this play, the pine occupies an important role. From ancient times in Japan people have believed that deities dwell in the pine tree and often called it Chitose (thousand years) in Japanese poetry because of its evergreen nature. The pine represents the celebration of longevity. It also has different sexes, which reminds people of husband and wife. According to the contents of this play, during the Engi period ( 901-923 ) under the reign of Emperor Daigo, Tomonari, a Shinto priest of Aso shrine in Kyushu, stops at a scenic beach, Takasago no Ura, in Harima province on his way to sightseeing in Kyoto with his retinue. While Tomonari is waiting for a villager, an immaculate old couple appears. Tomonari asks the couple who are sweeping up the needles under a pine tree to tell him the tale associated with the pine. The couple explains that the pine is the renowned Takasago Pine, which is paired with the Suminoe Pine, growing in distant Sumiyoshi; together they are called Aioi-no Matsu. Ze’ami composed this play based on a phrase in Kanajo preface to the Kokinshu, “Two pines of Takasago and Suminoe seem to be a pair.” Ze’ami honoured the longevity and harmonious relationship of the old couple, and composed the blessed longevity of the pine tree. At the beginning of the play a Shinto priest and his attendants are on their way by sea from Kyushu to Miyako and land at the Bay of Takasago in order to visit its famous pine tree. Yoro90 is one of the kami Noh, created by Ze’ami, it has a different structure from the other Ze’ami’s kami Noh, such as Takasago. This drama follows the pattern of kami Noh, which is that after the interlude, a deity appears and dances as a blessing. In the content, the auspicious signs, a deity of a mountain, who claims to be an incarnation of Willow Bodhisattva, appears and dashingly dances to bless the peace of the world. However, unlike the other dramas, in which a holy incarnation of a deity appears to narrate an ancient story, the Mae shite and tsure in this drama are the humans who found the spring. The background of the play, Kamo91 also is the concepts of Shintoism. Here, story is related to the Kamo shrine. One summer, a priest who serves the deity Muro no Myojin in the province of Harima visits Kyoto and enters the Kamo shrine which he has heard enshrines the same god as Muro no Myojin. At the shrine the 15 priest notices an altar into which is thrust an arrow which has white feathers. Later village women describe the detail of the history of Kamo shrine. There, then appears before the priest a deity of a lower ranking shrine; who narrates the story again and dances. After a while, the deity of Mioya finally reveals itself in the form of a celestial maiden. She beautifully performs the dance of a celestial maiden. Furthermore, the deity of Wakeikazuchi also briskly appears and shows his divine dignity by calling forth a thunderstorm92. This play which comprises a story around a myth related to the famous Kamo shrine in Kyoto belongs to the Waki Noh, or the Noh of gods. The drama entitled Kokaji93 (The Sword smith) also was based on Shinto background. Here, one character, Munechika, visits Inari shrine where he prays and requests the assistants of the guardian deity of his clan. At the shrine, a mysterious boy calls to him. When Munechika goes home, dresses himself for smiting and prays on his platform, there appears before him the deity to Inari who transform into the spirit of a fox. The deity announces that he will work as the partner of Munechika. The boy who appeared a moment earlier was the transformed Inari deity himself. References: 1 Komparu,Kunio (1983),The Noh Theatre, John Weatherhill, Inc-New York, P.xi 2 Maruoka, Daiji, Yoshikoshi, Tatsuo (1985), Noh,12th edition, Hoikusha, P.98 3 Oneil, P. G. (1984), AGuide to No, Hinoki Shoten, P14 4 Nogami, Toyoichiro (1973), Ze‟ami and his Theories on Noh,Tokyo,P.12 5 Ernest, Earle (1956), The Kabuki Theatre, The University of Hawaii, P.1 6 Waley, Arthur (1984), The No Plays of Japan, Tokyo, P.15 7 Sekine, Masuru (1985), Ze‟ami and his Theaories of Noh Drama, Tokyo, P.19 8 Motokiyo, Ze‟ami (1975), The Fushikaden, Tran. Shimada Shohei, Tokyo, P.12 9 T. F. P. 49 10 T. F. P.50,51 11 Z.H.T.N.D. P.23 12 Z.H.T.N.D. P.2 13 Z.H.T.N.D. P.28 14 Z.H.T.N.D. P29 15 Z.H.T.N.D. P.7 16 Z.H.T.N.D. P.32 17 Masakazu, Yamazaki (1984), On the Art of the No Drama, Princeton, P.174 16 18 O.A.N.D. P.173,176 19 O.A.N.D. P176 20 Z.T.N. P.8 21 Fu, The Translator to the reader, P. v 22 Z.T. N. P.16 23 Z.H.T.N.D. P.37 24 Ze‟ami and Zenchiku (1974), Kyakuraika p.246 25 Z.H.T.N.D. P.43 26 Z.H. T. N. D. P.3 27 N. P.98 28 Arnott, Peter (1966), The Theatre of Japan, U.K. P.112,113 29 T.T.J. P.62 30 Keen, Donald (1977), Anthology of Japanese Literature,New York, P.258 31 Z.T.N. P.23 32 Japanese Classics Translation Committee (1982),The Noh Drama, Tokyo. 33 T.N.T. P.43 34 T.N.T. P.150 35 Z.H.T.N.D. P.45 36 Senzai, Sanbasho, Okina 37 Z.H.T.N.D. P.46 38 T.N.D. P.4 39 Z, H.T.N.D. P. 50,51 40 T.N.T. P.36 41 Bowers, Faubion (1984), Japanese Theatre, Tokyo, P.147,159 42 N. P.116 43 Z.H.T.N.D. P.56 44 T.N.T. P.77 45 A.G.N. P.10 46 T.N.D. P. 147-159 47 T.F. P.24-25 48 Z.H.T.N.D. P.66 49 T.N.D. P.163 50 O.A.N.D. P.xxvii 51 T.N.T. P.39 52 Suichi, Kato (1979), A History of Japanese Literature, Kodansha International Ltd. P. 310 53 T.T.J. P.86 17 54 T.N.T. P.45 55 O.A.N.D. P.165 56 T.T.J. P.87 57 T.N.T. P.158 58 A.G.N. P. 7 59 T.N.T. P.126-127 60 T.T.T. P.83 61 T.N.P.J. P.19 61a T. N.P. P.19 62 T.N.T. P.161 63 T.N.T. P.168 64 T.N.T. P.257 65 T.N.T. P.259 66 T.N.T. P.263 67 T.N.T. P.269 68 http/encyclopedia2 the free dictionary.com/Shinto 69 Sokyo, Ono (1962),Shinto; The Kami Way, Rutland vt; Charls E.Tuttle Co. P.2 70 Hoffman,Michael (2010), In The Land of the Kami, Japan Times, March 14 71 S P.56 72 http/www.1000 questions.net/en/religion/Shinto.html. 73 http;/mb-soft.com/believe/two/Shintois.htm. 74 Pilgrim, Richard, Elwood, Robert (1985), Japanese Religion, New Jersey. 75 http;/mb-soft.com/believe/txo/shintois.htm 76 http;/mb-soft.com/believe/txo/Shinto.htm 77 Kobayashi,Kazushige, Knecht, Peter (1981) On the meaning of Masked dances in Kaguras, Asian Folklore Studies, P.3 78 http;/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shinto 79 http;/encyclopedia2 the free dictionary.com/Shinto 80 T.N.P.J. fourth edition 81 T.N.T. Tenth edition 82 T.N.P.J. 83 http;/www.the-noh-com/en/plays/data/program 026.html 84 http;/www.the-noh-com/en/plays/data/program 026.html 85 http;/www.the-noh.com/en/plays/data/programs 058. Html 86 T.N.D. 87 http;/www.the.noh.com/en/plays/data/program-017 18 88 T.N.P.J. 89 http;/www.the-noh.com/en/plays/data/program 020.html 90 http;/www.the-noh.com/en/plays/data/program/-037.html 91 http;/www.the-noh.com./en/plays/data/program-032.html 92 Dammananda, K.Sri (1994), Buddhism as a religion,Malaysia, P.10 93 B.A.R. P.10,11 19