FERNE Stroke Case Study

advertisement

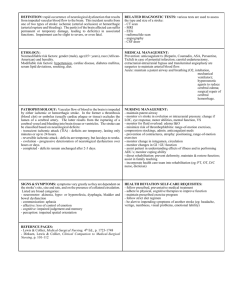

Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS A 52-year-old police officer, with a history of hypertension and smoking, is having dinner with his wife when he develops sudden onset of difficulty speaking, with drooling from the left side of his mouth, and weakness in his left hand. The family noted that the symptoms began just as the evening news was starting. His wife asks him if he is all right and the patient denies any difficulty. His symptoms progress over the next ten minutes until he cannot lift his arm and has trouble standing. The patient continues to deny any problems. The wife sits the patient in a chair and calls 911. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 2 of 21 Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Case Details PMHX + HTN No history of migraines, seizures, prior stroke, diabetes MEDS ACE inhibitor VS BP 150/80 P 89 R 20 T 98.9 SaO2 95% Physical Exam Well appearing, awake middle-aged male, in no acute distress. HEENT: NC/AT, no contusions Neck supple, NT. No JVD or bruits CV: RRR, φ MRG Lungs: CTA, φ WRR Abd: Soft, non-tender. Extremities: Warm and dry. No clubbing, cyanosis, or edema Neuro: Mental status Awake, responsive, and appropriate Patients answers correctly, and follows commands Cranial nerves Mild left facial droop. Forehead moves symmetrically PERRL / EOMI except for slight difficulty crossing midline to left Visual fields Intact bilaterally but difficult to assess Motor Right arm and leg extremity with 5/5 strength Left arm cannot resist gravity, left leg with mild drift Sensation Intact bilaterally to fine touch. Neglect Mild neglect to left side of body however can be corrected. Ataxia None with heal to shin and finger to nose Language Expressive and receptive language intact Mild to moderate dysarthria. Able to protect airway NIHSS 8 Laboratory Evaluation CBC, renal, and ECG unremarkable. Glucose 100 Noncontrast head CT (performed 1.5 hours from symptom onset) No intracranial hemorrhage or mass lesions. Suggestion of early ischemic changes in right hemisphere (mild loss of insular ribbon and subtle loss of gray-white matter interface) but no large areas of hypodensity or mass effect. Impression 52 year old Caucasian male, with several risk factors for cardio and cerebrovascular disease, with symptoms consistent with a right middle cerebral artery distribution ischemic stroke, now 2 hours from symptom onset. What would you do? Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 3 of 21 Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Introduction Despite recent medical advances, stroke remains as one of the most feared disease to strike adults. Over 700,000 Americans suffer strokes each year, and it has a societal cost of over $40 billion dollars. Stroke remains the third leading cause of death and the number one cause of adult disability. Of all strokes, nearly 85% are ischemic; the remainder are intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhages. Within the past decade, care for all these forms of stroke, and especially ischemic, has evolved from being largely supportive and passive to being acutely interventional – attempting to limit and sometimes reverse the injury. Much of acute stroke care is and will remain the responsibility of the Emergency Physician, for “time is brain”. Ischemic stroke are often classified by the vascular distribution involved. Anterior circulation strokes, involving the territory served by the carotid arteries, represent over two thirds of all ischemic strokes. In the Lausanne stroke registry, 96% of all anterior circulation strokes involved the middle cerebral artery (MCA) distribution, 3% involved the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), and 1% involved the entire internal carotid (ICA) distribution. Posterior circulation strokes on the other hand involve regions supplied by the vertebral arteries and represent approximately one quarter of all strokes. The vascular distribution involved will determine the clinical features of the stroke and often produce typical “stroke syndromes” discussed later in the text. Emergency Department Evaluation In the past several years, stroke advocates have been stressing the importance of the “Seven Ds”. (Table 1)[1,2,3,4] This mnemonic highlights the essential aspects of acute stroke care delivery. Remarkably, almost all of the steps can and will involve the Emergency Physician. Table 1. Detection Dispatch Delivery Door Data Decision Drug The 7 “D’s” of Stroke Management The awareness of stroke signs and symptoms by the patient Activation of EMS systems, priority dispatch, and rapid EMS response Rapid transport to the appropriate facility, en-route assessment, and prehospital notification Emergency department triage Emergency department evaluation (Neurologic evaluation - NIH stroke scale, glucose, head CT) Selection of appropriate therapy Delivery of therapeutics EMS systems play a crucial role in acute stroke care. Since the approval of tPA for stroke, EMS personnel have been one of the first groups to change their approach to stroke patients. In general, they now view stroke as an emergency, on par with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and trauma. Dispatch priorities now place stroke at the top and rapid transport to the hospital the Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 4 of 21 rule. Prehospital care providers can begin the process of stroke evaluation, with tools such as the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke scale, and can save the receiving physician significant time.[5,6] The Emergency Department (ED) and ED physician play a crucial role in timely and effective stroke care delivery. Similar to trauma and acute myocardial infarction (AMI), acute stroke patients should receive the highest priority in the ED. To achieve the time targets set forth by the NINDS consensus panel and recommended by the AHA in the ACLS guidelines, pathways or protocols that are well known and rehearsed need to be in place before the stroke patient arrives. [4,7,8,9] This requires a team approach, analogous to the trauma team, comprised of physicians and nurses from emergency medicine as well as neurology and radiology. It is difficult to effectively treat acute stroke patients without this team approach and to ensure continuity of care once the patients are admitted to the hospital.[10,11] The rapid evaluation and treatment of stroke patients occurs in parallel, requiring the history of present illness, physical exam, and initial management all to proceed simultaneously. As with all patients presenting to the ED, the ABCs remain paramount. Ischemic strokes, unless very large, tend not to cause immediate problems with airway patency, breathing abnormalities, or circulation issues. On the other hand, intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage patients will frequently require intervention with both airway protection and ventilation. Regardless of the stroke etiology, attention to the ABCs is first and foremost. History of Present Illness The history alone can be very suggestive as to the cause of the patient’s symptoms and will help create a focused differential diagnosis. Frequently the potential stroke patient cannot provide much of the history surrounding the event so family members, coworkers, bystanders, and EMS professionals are very important sources of information. Essential elements of the history include: the exact time of onset or the last time the patient was last seen at baseline, whether any seizure activity was noted to precede the onset of symptoms, recent migraine headaches, any trauma or neck injury in the preceding days, and if the patient had any recent illnesses. Not only are these important to making the correct diagnosis but will also dictate which therapies will be available to the patients. The exact time of symptom onset or the last time the patient was seen at their baseline is the most crucial piece information. Currently ischemic strokes that are greater than 3 hours from symptom onset are not eligible for thrombolytic therapy. From animal and human data, neuronal tissue suffers irreparable injury after relatively brief periods of ischemia, and by 3 hours, little viable tissue remains. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, including Xenon CT and diffusion / perfusion weighted MRI may identify patients beyond the 3 hour window who may still have salvageable penumbral tissue. The past medical history and current medications are of importance. This information can not only help prioritize items on the differential diagnosis but may determine eligibility for specific therapeutic interventions. Medical records, primary care physicians, family members, and EMS personnel again play a vital role. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 5 of 21 Physical Examination It is worth restating that the ABCs are paramount. Stroke patients can quickly deteriorate and constant reassessment is critical and strict attention to vitals signs equally important. Many stroke patients are hypertensive at baseline and their blood pressure can be even more elevated after stroke. Cardiac arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, are commonly found in stroke patients. The physical examination must investigate all the major organs systems. Ischemic strokes can originate in the major vessels of the chest or neck, arise from cardiac sources, or develop in-situ. The physical examination can help determine the potential cause of the stroke. Commonly strokes occur concurrently with other acute conditions such as AMI, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation/flutter, carotid or vertebrobasilar dissections, and less commonly with thoracic aortic dissections. The neurologic examination is paramount and yet is perhaps the weakest area of training in most Emergency Medicine residencies. While a thorough neurologic examination similar to those taught in medical school can take nearly an hour to perform, a directed and focused exam can be performed in minutes and provide great insight into not only the potential cause of the patients deficits, but help determine the intensity of treatment required. A very useful tool in measuring neurologic impairment is the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).[12] This scale is easily performed, reliable and has been validated in several studies of both neurologist, and non-neurologist physicians and nurses. The NIHSS provides insight to the location of vascular lesions and is correlated with outcome in ischemic stroke patients. It focuses on 5 major areas of the neurologic examination: level of consciousness, visual function, motor function, sensation and neglect and cerebellar function. The NIHSS is used by most stroke teams and stroke neurologists, and quickly describes to the consultant the severity and possible location of the stroke. It is strongly associated with outcome with and without thrombolytics, and can predict those patients likely to respond to or develop hemorrhagic complications from thrombolytic use. Differential Diagnosis The history and physical examination, combined with neuro-imaging, narrows the differential diagnosis and can usually identify the cause of the patients’ symptoms. As noted in table 2, many disease processes may mimic a stroke. One of the most common stroke mimics is hypoglycemia. Rapid serum glucose measurement, frequently in the prehospital setting, can identify these patients before the stroke protocol is even activated. Complicated migraines present a particular challenge to physicians. These tend to occur in younger patients, typically women, and may appear very much like a stroke. Advanced imaging techniques can help clarify the cause of the patients’ symptoms. Lastly, Todd’s paralysis can resemble an acute stroke, and only a history of seizure by the patient or more commonly, by the family who was with the patient at the symptom onset, indicates seizures as the cause of the focal neurologic deficits. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 6 of 21 Table 2. Differential Diagnosis of Potential Stroke Patients Most Common Less Common Encephalitis / Meningitis Complicated migraine Hyponatremia Intracerebral hemorrhage Neoplasm Hyperglycemia Psychiatric Hypertensive encephalopathy Subdural hematoma Hypoglycemia Toxicologic Post-ictal paralysis (Todd’s) Trauma Stroke Syndromes Most ischemic strokes involve the anterior circulation, especially the middle cerebral artery. Clinical symptoms in ischemic stroke can be explained by understanding the cerebral arterial distributions of the cortices, cerebellum, and brainstem (Table 3). Neurologic symptoms that correspond to a specific vascular distribution further support the diagnosis of stroke and help guide the intensity of treatment. Lacunar strokes have the best functional outcomes, with more than 80 percent of patients having minimal or no impairment at 1 year. Dominant hemispheric strokes are especially disabling since the patients expressive and receptive language is impacted. Furthermore, occlusions of the entire MCA or ICA distributions have very poor prognoses with early mortality approaching 50% and nearly all patients left with severe disability. While the NINDS trial showed modest benefit to patients with these large strokes, more recent studies suggest better response to intra-arterial thrombolysis versus intravenous thrombolysis alone. Table 3. Stroke Syndromes Vascular Territory Anterior cerebral Middle cerebral – dominant Middle cerebral – nondominant Posterior cerebral Lacunar – Pure motor – Pure sensory – Clumsy hand / dysarthria Typical Neurologic Symptoms Contralateral hemiparesis leg > arm, face; Contralateral sensory loss; Change in personality, speech perserveration; Bilateral occlusions produce paraplegia, anarthria, akinetic mutism Contralateral hemiparesis arm, face > leg; Contralateral sensory loss; Contralateral homonymous hemianopia; Ipsilateral eye deviation; Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasias Contralateral hemiparesis arm, face > leg; Contralateral sensory loss with extinction; Contralateral homonymous hemianopia; Ipsilateral eye deviation; Ipsilateral hemineglect, inattention, extinction on double stimulation Contralateral hemianopia (patient frequently unaware); Brain stem findings (varied); Bilateral occlusions produce cortical blindness - Contralateral paresis or plegia of face, arm, leg - Contralateral decreased sensation of face, arm, leg - Slurred speech, and weakness and ataxia of the arm Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 7 of 21 Emergency Department Treatment General Care The goal of Emergency Department acute stroke management is speed and efficiency, stroke patient evaluation and treatment should be performed within 1 hour from presentation. Again, the general management is a team effort with the nursing and physician staff working closely together (Table 4). Table 4. General Management of Acute Stroke Patient Treat hypoglycemia with D50; Blood glucose Treat hyperglycemia with insulin if serum glucose over 300 mg% See recommendations for thrombolytic and nonthrombolytic candidates Blood pressure Observe for ischemic changes or atrial fibrillation Cardiac monitor Intravenous fluids Avoid D5W and excessive fluid administration IV normal saline at 50 cc / hr unless otherwise required Aspiration risk is great, avoid oral intake until swallowing assessed NPO Supplement if indicated (Sa02 < 90%) Oxygen Temperature Avoid hyperthermia, oral or rectal acetaminophen as needed While not as “sophisticated” as thrombolytics, these basic care issues are of great importance in stroke care. Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia need to be identified and treated early in the evaluation. Not only can both produce symptoms that closely mimic an ischemic stroke, but also both can aggravate ongoing neuronal ischemia. Administration of glucose in hypoglycemia produces profound and prompt improvement, while insulin should be started on those stroke patients with hyperglycemia. Hyperthermia is infrequently associated with stroke but can cause increased morbidity. Administration of acetaminophen, by mouth or per rectum, is indicated in the presence of elevated temperature. Lastly, supplemental oxygen is needed only when the patient has a documented oxygen requirement. No evidence to date suggests that supernormal oxygenation improves outcome, and some studies suggest it may worsen it. Blood pressure management From prehospital care to Emergency Department staff, there is a preoccupation with hypertension. The current guidelines for blood pressure management in acute stroke are shown in table 5. As shown, unless there is significant hypertension, or other comorbid conditions that require hypertensive control, most patients equilibrate over the first several hours, and many older patients with longstanding hypertension actually require supernormal pressures and will worsen if they are artificially made normotensive, as penumbral tissue will be compromised and potential watershed infracts may arise. The exception to hypertension “tolerance” is in those patients who may be thrombolytic candidates. Because hypertension is an exclusion criterion to thrombolytic therapy, “gentle” attempts may be made to bring the stroke patient to within treatable ranges. Patients who require Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 8 of 21 more “aggressive” management, such as nitroprusside or labetalol drips, are not eligible for thrombolytic therapy. Table 5. Blood Pressure Management (adopted from ACLS guidelines) Fibrinolytic candidates Labetalol 10-20 mg IVP 1-2 doses or Pretreatment Nitropaste 1-2 inches or SBP > 185 or Enalapril 1.25 mg IVP DBP > 110 mm Hg 1. Sodium nitroprusside (0.5 µg/kg/min) Post-treatment* 2. Labetalol 10-20 mg IVP over 1 to 2 minutes 1. DBP > 140 mm Hg and consider a labetalol drip at 2-8 mg/min 2. SBP > 230 mm Hg or 3. Labetalol 10 mg IVP, may repeat and DBP 121 to 140 mm Hg double every 10 to 20 minutes up to a maximum 3. SBP 180-230 mm Hg or dose of 150 mg DBP 105-120 mm Hg Non-fibrinolytic candidates 1. DBP > 140 mm Hg 2. SBP > 220 or DBP 121 to 140 mm Hg or MAP > 130 mm Hg 3. SBP < 220 mm Hg or DBP 105 to 120 mm Hg or MAP < 130 mm Hg 1. Sodium nitroprusside 0.5 µg/kg/min Reduce approximately 10-20% 2. Labetalol 10-20 mg IVP over 1-2 minutes. May repeat and double every 20 minutes up to a maximum of 150 mg. 3. Antihypertensive therapy is indicated only if acute myocardial infarction , aortic dissection, severe CHF or hypertensive encephalopathy are present. ∗ Monitor vital signs every 15 minutes for 2 hours, then every 30 minutes for 6 hours, then every hour for 16 hours. Patient Selection The NINDS trial and subsequent post-hoc analyses have shown that patients should be selected to receive thrombolytic therapy according to the original guidelines in the NINDS trial (Table 6).[13,14,15] No pretreatment patient information significantly affected patients’ response to thrombolytics. In general, increasing age, a history of diabetes, larger strokes based on the NIH stroke scale (>20), and early CT findings (edema, hypodensity) are associated with worse outcome regardless of therapy, but no subgroup has been found to have a differential response to thrombolytics. Patients at increased risk for post-thrombolytic intracerebral hemorrhage include those again with larger strokes (NIHSS > 20) and early CT changes. Other factors associated with increased risk of hemorrhage include thrombolytic administration beyond the 3 hour window, incorrect dosing of tPA (> 0.9 mg/kg or 90 mg maximum), elevated post-thrombolytic blood pressure, and possibly post-thrombolysis anticoagulation.[16,17,18,19] Strict adherence to the protocol will minimize these preventable errors. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Table 6. Page 9 of 21 Indications and Contraindications to tPA Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke Indications: 1. Acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours from symptom onset 2. Age greater than 18 years old (rt-PA has not been studied in pediatric stroke) Contraindications: 1. Evidence of intracranial hemorrhage on pretreatment evaluation 2. Suspicion of subarachnoid hemorrhage 3. Recent stroke, intracranial or intraspinal surgery, or serious head trauma in the past 3 mos 4. Major surgery or serious trauma in the previous 14 days* 5. Arterial puncture at a non-compressible site or lumbar puncture in the previous 7 days* 6. Major symptoms that are rapidly improving or only minor stroke symptoms* 7. History of intracranial hemorrhage 8. Uncontrolled hypertension at the time of treatment 9. Seizure at the stroke onset 10. Active internal bleeding 11. Intracranial neoplasm, arteriovenous malformation, or aneurysm 12. Known bleeding diathesis including but not limited to: • Current use of anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin) or an International Normalized Ratio (INR) > 1.7 or a prothrombin time (PT) > 15 seconds • Administration of heparin within 48 hours preceding the onset of stroke and an elevated activated partial thromboplastin time at presentation • Platelet count < 100,000/mm3 *In the NINDS trial, not present in current package insert Fibrinolytic Therapy – How To Key to timely thrombolytic delivery is to calculate and prepare the t-PA dose early on in the evaluation. To minimize complications adherence to the correct dose is very important. The correct dosing of rt-PA is 0.9 mg/kg (90 mg maximum); a bolus of 10% of the total dose over 12 minutes, and then the remaining 90% as an infusion over 1 hour. If thrombolytics are administered, no concomitant heparin, warfarin, or aspirin should be used during the first 24 hours after treatment. If heparin or any other anticoagulant is indicated after 24 hours, a non-contrast CT scan or other neuroimaging method should be performed to rule out any intracranial hemorrhage before starting an anticoagulant. Fibrinolytic Therapy – After rt-PA: Blood pressure management Patients who have received rt-PA for their ischemic stroke, either IV or IA, require strict blood pressure control (table 5). Unlike most instances in the ICU where repeat readings are performed for an elevated blood pressure, prompt action must be taken the very first time a blood pressure elevation is obtained. The greatest risk to patients within the first 12 to 24 hours post thrombolysis is hemorrhage, and elevated blood pressure contributes to this risk. The choice of antihypertensive agent is largely dependent on the severity of the hypertension. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 10 of 21 Fibrinolytic Therapy – After rt-PA: Suspected intracerebral hemorrhage Physicians who administer thrombolytics need also to prepare for intracerebral hemorrhage. While the risk is relatively small, the consequences of hemorrhage after thrombolytics are grave, with nearly half of all patients dying shortly afterward. Preparation is key and constant monitoring and patient reassessment crucial in identifying and treating ICH. Other Interventions While the “Decade of the Brain” began with much fanfare and high expectation, the results of most clinical trials for acute stroke have been disappointing. To date, no pharamacologic agent, aside from rt-PA, has been approved for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Except perhaps in special situations, such as critical carotid stenoses, stuttering symptoms, or posterior circulation strokes, unfractionated and low molecular weight heparins are not indicated in acute ischemic stroke. Aspirin on the other hand has been shown to provide some benefit, both short and long term. In patients not suited for thrombolytics, aspirin should be administered within 24 hours. Seizures and Increased Intracranial Pressure Two complications of acute stroke, seizures and increased intracranial pressure, rarely occur within the time the stroke patient is being evaluated in the Emergency Department but are important to remember. Seizures are not uncommon, occurring in 1-10% of all strokes. Seizures can cause early clinical deterioration and are associated with higher in-hospital mortalities. Strokes with cortical involvement, larger strokes, and hemorrhagic strokes have a higher incidence of seizures. Studies suggest seizures will develop early, with roughly a quarter occurring within the first 24 hours from stroke onset. Benzodiazepines are the drugs of choice and are used in a similar fashion to non-stroke related seizures. Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) is a life-threatening event associated with up to 20% of all strokes, and more commonly found in large strokes. Edema and herniation produces significant mortality in patients with hemispheric stroke. Similar to increased ICP secondary to closed head injury, position, hyperventilation, hyperosmolar therapy, and rarely barbiturate coma can be used. More recently, preliminary studies of hemicraniectomy to immediate reduce lifethreatening ICP have suggested benefit if performed before clinical deterioration.[20] Disposition Establishing pathways and protocols for acute stroke treatment not only assist in the immediate management of the stroke patient while in the E.D., but also assure attention to preventing the early complications of stroke and begins the evaluation for the cause of the current stroke as well as initiation of risk factor reduction to prevent reoccurrence. Stroke pathways often include carotid ultrasound, speech assessment, and cerebrovascular evaluation, often within the first day. This organized approach not only decreases length of hospitalization and total expenditures, but also leads to better outcome and lower morbidity. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 11 of 21 All patients who receive rt-PA require admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) setting. There they will: 1) receive intensive neurologic monitoring for signs of deterioration due to edema, infarct extension, or intracerebral hemorrhage, 2) undergo strict blood pressure control, 3) be observed for systemic hemorrhagic complications, and 4) treated for many of the co-morbid illness that coexist with stroke patients. Patients that do not receive thrombolytics should receive aspirin and may be admitted to locations with lower levels of acuity appropriate for the general condition of the patient.[21,22] Lastly, early mobilization, swallowing assessment, and physical therapy / occupational therapy translates into shorter hospitalizations and more rapid recovery. Future Directions The future remains bright for the development of new therapies for stroke. While initial trials of pharamacologic agents, such as neuroprotectives and low molecular weight heparins, were negative, newer agents are in Phase II and III clinical trials. Ongoing stroke trials involve newer neuroprotectives and antiplatelet agents, such as the IIb IIIa glycoprotein. The newest large NINDS funded trial is the Interventional Management of Stroke trial, investigating thrombolytic delivery via intra-arterial catheterization in combination with a lower intravenous dose given prior to angiography.[23] Recent small trials have demonstrated superior rates of restoring vessel patency with improved outcome. Again, mimicking the cardiac arena, catheters for mechanical clot removal are also under investigation. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 12 of 21 Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Reference List 1. Pancioli AM, Broderick J, Kothari R, Brott T, Tuchfarber A, Miller R, Khoury J, Jauch E. Public perception of stroke warning signs and knowledge of potential risk factors. JAMA. 1998 Apr 22-29;279(16):1288-92. 2. Kothari R, Jauch E, Broderick T, et al. Acute stroke: delays to presentation and emergency department evaluation. Ann Emerg Med. 1999; 33:3 -8. 3. American Heart Association. Textbook of Advanced Cardiac Life Support. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association,1997 . 4. Marler JR, Emr M, Jones P (eds). Proceedings of a National Symposium on Rapid Identification and Treatment of Acute Stroke. Bethesda, MD: The National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institutes of Health, Aug 1997. 5. Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T, et al. Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: reproducibility and validity. Ann Emerg Med.1999; 33:373 -8. 6. Alberts MJ, Hademenos G, Latchaw RE, Jagoda A, Marler JR, Mayberg MR, Starke RD, Todd HW, Viste KM, Girgus M, Shephard T, Emr M, Shwayder P, Walker MD. Recommendations for the establishment of primary stroke centers. Brain Attack Coalition. JAMA. 2000 Jun 21;283(23):3102-9. 7. Adams HP Jr, Brott TG, Crowell RM, Furlan AJ, Gomez CR, Grotta J, Helgason CM, Marler JR, Woolson RF, Zivin JA, Feinberg W, Mayberg M. Guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke.. 1994;25:1901-1914. 8. Adams HP, Brott TG, Furlan AJ, Gomez CR, Grotta J, Helgason CM, Kwiatkowski T, Lyden PD, Marler JR, Torner J, Feinberg W, Mayberg M, Thies W. Guidelines for Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Stroke: A Supplement to the Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Circulation 1996 94: 1167-1174 9. Part 7: The Era of Reperfusion : Section 2: Acute Stroke, Circulation 2000 102 [Suppl I]: I204 - I-216. 10. Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Larsen K, Hubbe P, Olsen TS The effect of a stroke unit: reductions in mortality, discharge rate to nursing home, length of hospital stay, and cost. A community-based study. Stroke. 1995 Jul;26(7):1178-82. 11. Wentworth DA, Atkinson RP. Implementation of an acute stroke program decreases hospitalization costs and length of stay. Stroke. 1996 Jun;27(6):1040 12. Adams HP Jr, Davis PH, Leira EC, etal: Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology 1999; 53: 126-131 13. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, Toni D, Lesaffre E, von Kummer R, Boysen G, Bluhmki E, Hoxter G, Mahagne MH, Hennerici M, for the ECASS Study Group. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 13 of 21 stroke: the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA.. 1995;274:1017-1025. 14. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, Larrue V, Bluhmki E, Davis S, Donnan G, Schneider D, Diez-Tejedor E, Trouillas P Randomised doubleblind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998 Oct 17;352(9136):1245-51. 15. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med.. 1995;333:1581-1587. 16. Haley EC Jr, Lewandowski C, Tilley BC. Myths regarding the NINDS rt-PA Stroke Trial: setting the record straight. Ann Emerg Med. 1997 Nov;30(5):676-82. 17. The NINDS t-PA Study Group. Generalized efficacy of t-PA for acute stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:2119-2125. 18. Tanne D, Gorman, MJ, Bates VE, et al. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic strokes in patients aged 80 years and older. Stroke. 2000;31:370-375. 19. Katzan IL, Furlan AJ, Lloyd LE, Frank JI, Harper DL, Hinchey JA, Hammel JP, Qu A, Sila CA Use of tissue-type plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: the Cleveland area experience. JAMA. 2000 Mar 1;283(9):1151-8. 20. Schwab S, Steiner T, Aschoff A, Schwarz S, Steiner HH, Jansen O, Hacke W. Early hemicraniectomy in patients with complete middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke. 1998 Sep;29(9):1888-93. 21. Chen ZM, Sandercock P, Pan HC, Counsell C, Collins R, Liu LS, Xie JX, Warlow C, Peto R Indications for early aspirin use in acute ischemic stroke : A combined analysis of 40 000 randomized patients from the Chinese acute stroke trial and the international stroke trial. On behalf of the CAST and IST collaborative groups. Stroke. 2000 Jun;31(6):1240-9. 22. CAST: randomized placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group. 23. Lewandowski, C. A., Frankel, M., Tomsick, T. A., Broderick, J., Frey, J., Clark, W., Starkman, S., Grotta, J., Spilker, J., Khoury, J., Brott, T. (1999). Combined Intravenous and Intra-Arterial r-TPA Versus Intra-Arterial Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke : Emergency Management of Stroke (EMS) Bridging Trial. Stroke 30: 2598-2605. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 14 of 21 Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Case Outcome The emergency physician, in collaboration with the Stroke Team, concluded that the patient’s symptoms were the results of an ischemic stroke. The patient met the time window for thrombolytics and had no exclusion to the therapy. After discussing the options with the patient and his family, he elected to receive thrombolytic therapy. He was given IV t-PA 0.9 mg/kg dose per protocol and admitted to the ICU. The next 24 hours were largely uneventful. He required a single, 10 mg dose of labetalol for an episode of elevated blood pressure. His symptoms began to improve an hour after the infusion, and continued over night. His examination at 24 hours post stroke revealed only a mild right arm drift and a mild right facial droop for a NIH stroke scale of 2. His leg weakness, visual field cut, and gaze palsy had all resolved. His 24 hour CT scan revealed two very small areas of developing hypodensity in the left parietal cortex, reflective of his residual deficits. On the first hospital day, his swallowing was assessed by a screening tool and found to be intact. A carotid duplex study revealed a stenosis of over 90% and after balancing the risk of recurrent stroke from surgery or recanalization vs. new embolic stroke from the stenosis, a carotid endarterectomy was performed on day 4. The patient continued physical therapy while hospitalized and was discharged home on day 7. Three months after his stroke, his only complaint was that his very mild right arm weakness had cost him several strokes in his previously scratch golf game. Final Thoughts Stroke was once a disease of little hope. For the first time ever in the history of medicine we can now begin to prevent the long-term morbidity and mortality of stroke and actively intervene before the damage is irreversible. Emergency Physicians and ED staffs are on the front line of this battle but we should not be alone in this fight. Hospital wide collaboration is essential to give stroke patients the best chance at a good outcome and a future without disability. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 15 of 21 Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Annotated Bibliography 1. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med.. 1995;333:1581-1587. This is the sentinel article describing the data that lead to the approval of tPA for stroke. This was a two-part study in which both independent parts showed sustained benefit for tPA in acute ischemic stroke within the first three hours from symptom onset. 2. Haley EC Jr, Lewandowski C, Tilley BC. Myths regarding the NINDS rt-PA Stroke Trial: setting the record straight. Ann Emerg Med. 1997 Nov;30(5):676-82. This brief commentary highlights several of the misconceptions regarding the NINDS trial. The authors, from Emergency Medicine and Neurology, provide a very insightful review and interpretation regarding the NINDS data. 3. Adams HP Jr, Brott TG, Crowell RM,et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke.. 1994;25:1901-1914. American Heart Association Stroke Update. Part 7: The Era of Reperfusion. Circulation 2000;102(suppl I):I.204-216. (in press) The American Heart Association provides leadership in the establishment of treatment guidelines for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases. This initial consensus paper established the basic treatment steps regarding acute ischemic stroke. The newer update utilizes information gained over the past 4 years of thrombolytic use and makes modifications to the original recommendations. 4. Adams HP, Brott TG, Furlan AJ, et al. Guidelines for Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Stroke: A Supplement to the Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Circulation 1996 94: 1167-1174. This is an evidence based medicine supplement to the ischemic stroke guidelines that reviews the data for thrombolytics stroke and establishes recommendations for thrombolytic administration. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS 5. Page 16 of 21 Spilker JS, Knogable G, Barch J, et al. Using the NIH Stroke Scale to assess stroke patients. The NINDS rt-PA Stroke Study Group. J Neurosci Nurs. 1997 Dec; 29(6):384-92. The NIH stroke scale has been shown to be not only an efficient and reproducible measure of neurologic deficit, but also highly correlates with not only outcome but also identifies patients at higher risk of hemorrhage after thrombolytics. 6. Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T, et al. Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: reproducibility and validity. Ann Emerg Med.1999; 33:373 -8. Prehospital care plays a critical role in the treatment of acute stroke. One component is to recognize potential stroke patients. Without burdening the prehospital care providers the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale is a quick and easy neurologic assessment tool with good sensitivity for anterior circulation stroke. EMS personnel can provide early notification and consider triage to appropriate hospitals. 7. Donnan GA, Davis SM, Chambers BR, et al. Streptokinase for acute ischemic stroke with relationship to time of administration: Australian Streptokinase (ASK) Trial Study Group. JAMA. 1996 Sep 25; 276(12):961-6. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study. JAMA. 1995 Oct 4; 274(13):1017-25. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998 Oct 17; 352(9136):1245-51. Randomized controlled trial of streptokinase, aspirin, and combination of both in treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Multicentre Acute Stroke Trial--Italy (MASTI) Group. Lancet. 1995 Dec 9; 346(8989):1509-14. Thrombolytic therapy with streptokinase in acute ischemic stroke. The Multicenter Acute Stroke Trial--Europe Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996 Jul 18; 335(3):14550. These five papers represent the major streptokinase and rt-PA publications regarding acute treatment of stroke. Frequently, they will be used for comparison with the NINDS trial or used in meta-analyses. They do provide insight on the evolution of the current stroke recommendations and how the NINDS protocol was developed and later accepted. For more information, please refer to the Thrombolytic Therapy for Stroke presentation. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS 8. Page 17 of 21 Donnan GA, Davis SM, Chambers BR, et al The rt-PA (alteplase) 0- to 6-hour acute stroke trial, part A (A0276g) : results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke study investigators. Stroke. 2000 Apr; 31(4):811-6. Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998 Oct 17; 352(9136):1245-51. These two studies / substudies demonstrated the need to administer thrombolytics within 3 hours. Attempts to extend the therapeutic window were met with no change in outcome compared with placebo, and exposed the patients to increased of hemorrhagic complications. 9. Solomon NA, Glick HA, Russo CJ, et al. Patient preferences for stroke outcomes. Stroke. 1994 Sep;25(9):1721-5. Solomon was one of the first (and few) authors who looked at patients’ perceptions of stroke outcomes. This article is key to understanding the risks of stroke treatment options. The risks belong to the patient, and an act of omission (i.e. no treatment) can lead to worse outcomes than an act of commission. Food for thought. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 18 of 21 Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Questions 1. Which is not a typical symptom of anterior circulation ischemic strokes? a. Unilateral arm, face, and leg weakness b. Hemianopia c. Headache d. Slurred speech e. Aphasia 2. Which is a contraindication to thrombolytic therapy? a. A stroke 2 weeks prior b. A history of seizures c. Serum glucose of 80 mg/dl d. Age greater than 80 years old e. NIH stroke scale of 5 3. Which CT findings are signs of early ischemia? 1. Loss of the insular ribbon 2. Hypodensity 3. Dense middle cerebral artery sign 4. Loss of gray – white matter differentiation a. 1, 2 b. 2, 4 c. 1, 2, 3 d. All the above 4. The degree of neurologic deficit measured by the NIHSS is correlated with: 1. Size of infarct seen on follow-up CT 2. Risk of hemorrhage in patients receiving thrombolytics 3. Outcome 4. Likelihood of effect from tPA 5. Need for blood pressure control a. 1, 2 b. 2, 4 c. 1, 2, 3, 4 d. All the above 5. Which of the following is true: a. A blood pressure of 200/110 in a non-thrombolytic stroke patient requires immediate treatment b. A blood pressure of 160/100 in a patient who is receiving thrombolytics requires immediate treatment Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 19 of 21 c. Oral clonidine is safe to use in acute stroke patients d. One or two doses of IV labetalol is an effective method to "gently" lower a stroke patient's blood pressure to allow them to receive thrombolytics Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Page 20 of 21 Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Answers 1. Answer c. Headache is not typical found in patients with ischemic stroke. Intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhages do have headache as part of their presenting signs and symptoms. 2. Answer a. A stroke two weeks prior would expose the patient to a high risk of hemorrhage into the area of previous stroke. tPA use within 3 months of prior stroke is not recommended. 3. Answer d. All are findings of ischemia. Only a large area of hypodensity (greater than one third of the middle cerebral artery distribution, is a contraindication to thrombolytics. If significant changes are seen within the first three hours from symptom onset, question the time of stroke onset. 4. Answer c. The NIHSS is a very useful tool to access the size of stroke but also provide insight into the likely prognosis of the patients and the chance for both effect from receiving thrombolytics but also the risk of hemorrhage afterwards. It has not been shown to correlate with the need for blood pressure control. 5. Answer d. Aggressive lowering of hypertension, with continuous IV infusions, is not recommended for patients who may be eligible for thrombolytics. Single boluses of labetalol or enalapril are commonly used agents to help gently lower blood pressure in patients who may be eligible for thrombolytic therapy. Most non-thrombolytic patients do not require aggressive blood pressure management and an ischemic stroke can be worsened by over treatment of blood pressure. Many stroke patients have long standing hypertension and relative iatrogenic hypotension may increase the region of ischemia. Other comorbid conditions, such as acute myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, and congestive heart failure, may require more aggressive blood pressure management. Oral agents should not be used due to the risk of aspiration. Ischemic Anterior Circulation Stroke Edward C. Jauch, MD, MS Appendix A Category 1a Level of Consciousness 1b LOC Questions (Month, Age) 1c LOC Commands (Open-close eyes, show thumb) 2 Best Gaze (Follow finger) 3 Best Visual (Visual fields) 4 Facial Palsy (Show teeth, raise brows, squeeze eyes shut) 5 Motor Arm Left* (Raise 90o, hold 10 seconds) 6 Motor Arm Right* (Raise 90o, hold 10 seconds) 7 Motor Leg Left* (Raise 30o, hold 5 seconds) 8 Motor Leg Right* (Raise 30o, hold 5 seconds) 9 Limb Ataxia (Finger-nose, heel-shin) 10 Sensory (Fine touch to face, arm, leg) 11 Extinction / Neglect (Double simultaneous testing) 12 Dysarthria (Speech clarity to “mama, baseball, huckleberry, tip-top, fifty-fifty”) 13 Best Language ** (Name items, describe pictures) Page 21 of 21 NIH Stroke Scale Description Score Alert Drowsy Stuporous Coma Answers both correctly Answers 1 correctly Incorrect on both Obeys both correctly Obeys 1 correctly Incorrect on both Normal Partial gaze palsy Forced deviation No visual loss Partial hemianopia Complete hemianopia Bilateral hemianopia Normal Minor Partial Complete No drift Drift Can’t resist gravity No effort against gravity No movement No drift Drift Can’t resist gravity No effort against gravity No movement No drift Drift Can’t resist gravity No effort against gravity No movement No drift Drift Can’t resist gravity No effort against gravity No movement Absent Present in one limb Present in two limbs Normal Partial loss Severe loss No neglect Partial neglect Complete neglect Normal articulation Mild to moderate dysarthria Near to unintelligible or worse No aphasia Mild to moderate aphasia Severe aphasia Mute 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 0 1 2 0 1 2 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 3 4 0 1 2 3 4 0 1 2 3 4 0 1 2 3 4 0 1 2 0 1 2 0 1 2 0 1 2 0 1 2 3 0 - 42 Total * For limbs with amputation, joint fusion, etc. score a “9”and explain. ** For intubation or other physical barrier to speech, score a “9” and explain