Ryanir Case Study - Staffordshire University

advertisement

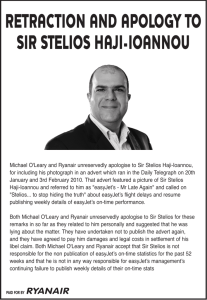

Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study RYANAIR Page 1 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study “Everyone always says, “What’s your secret? “It’s very simple. We’re like Wal-Mart in the US. - we pile it high and sell it cheap.” Michael O’Leary, CEO of Ryanair1 “Ryanair is the best imitation of Southwest Airlines that I have seen.” Herbert D. Kefleher, founder of Southwest Airlines2 “He (O’Leary) is almost certainly one of the most successful leaders in the industry, with a unique business model, discipline and an extraordinary level of confidence” Sir Michael Bishop, Chairman, BMI British Midland 3 “Ryanair has the financial and operational capacity to maintain its position as the dominant player in the low fares, no frills market, and indeed become one of Europe largest airlines.” Stephen Furlong, airline analyst, Davy Stockbrokers 4 RYANAIR CHALLENGES EASYJET In the summer of 2003, Michael O’Leary (O’Leary), the CEO of Ryanair, one of the oldest and most successful low-cost airlines of Europe, outfitted himself in combat gear and led a small army of Ryanair’s employees to Luton airport, the base of rival easyJet5. An Old World War II battle tank was also roped in to complete the effect. This was Ryanair’s way of ‘attacking’ the fares of easyJet, which, it claimed, were very high for a low-cost airline. O’Leary said he wanted to ‘liberate the public from the high fares of easyJet.’ Through this unconventional publicity stunt, O’Leary was able to get his message across successfully and create positive media attention for his airline. Ryanair was one of the first independent airlines in Ireland. Until Ryanair was set up in 1985, the Irish air services were almost exclusively under the control of Aer Lingus, the national carrier. Some other airlines, notably Avair, had been set up in Ireland before Ryanair, but most of them collapsed due to their inability to compete with the more powerful national carrier. The setting up of Ryanair was an important landmark in Irish airline history. Ryanair went through a few turbulent years of operation, but soon it managed to refocus itself successfully as a low-cost no-frills carrier, capturing a large share of the market for air services between England and Ireland. By the late 1990s, it was the largest low-cost airline in Europe. However, it was overtaken by easyJet when the latter took over Go, the low-cost subsidiary of British Airways (BA), to gain a larger market and a bigger combined fleet. (Refer Exhibit I for note on low-cost airlines in Europe). BACKGROUND NOTE Ryanair started operations in July 1985, flying between Waterford in the southeast of Ireland and London’s Gatwick airport. Three brothers, Catlan, Declan and Shàne Ryan were the founding shareholders of Ryanair, which was set up to offer low-cost no-frills services between Ireland and London. The airline began operations with a fifteen-seater turbo prop commuter plane which was leased to the company by Guinness Peat Aviation (GPA)6, of which their father, Tony Ryan, was the Chairman. Ryanair got an early break when, shortly after its formation, the UK and Irish governments signed a new air services agreement that deregulated air traffic between the two countries. In anticipation of the increased air traffic between the two countries, the Irish government decided to license a second Irish operator on the route from Dublin to London. Ryanair happened to be the only airline to apply for the license. It was granted the license to operate on the Dublin Page 2 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study (Ireland) Luton (London) route. By the end of the first year, Ryanair had carried 5,000 passengers and had 57 staff. To meet increased operational requirements, Ryanair purchased two more planes (24-year-old 50-seaters) from Dan Air. The airline quickly realized that it could capitalize on the market by offering cheap fares, and set its initial fare at IR £95 (1 Ireland Pound was equal to approximately 1.44 US Dollars) for a return ticket. The price was 20 percent lower than the cheapest fare of its competitors. Gradually, the airline replaced its old aircraft with newer aircraft purchased from TAROM, a Romanian air transport company. By the end of 1986, services to London were firmly established. However, further expansion had been blocked because the requisite licenses could not be obtained. To overcome this, Ryanair acquired an 85 percent stake in London European Airways (LEA, a Luton-based airline). LEA had been flying scheduled flights to Amsterdam and Brussels from London, but the flights had been suspended in early 1987. By May 1987, Ryanair had resumed services to both the cities. However, load factors were low on both the routes (around 45 percent), and the Amsterdam route had to be dropped later that year. The Brussels route also had problems and had to be more closely integrated with the parent company which was called Ryanair Europe. However, several difficulties cropped up and the scheduled routes had to be abandoned. The company repositioned itself as a charter tour operator flying to various destinations in the Mediterranean and Europe. In the summer of 1987, Ryanair started its first charter operation to over 65 locations around Europe. By the end of that year, the airline had carried over 400,000 passengers. 1988 started well, with Ryanair getting more licenses on new routes from Dublin, Knock, Cork and Shannon. However, attempts to develop new routes from Dublin to Manchester and Glasgow came up against entrenched competition from Aer Lingus, which slashed prices and increased capacity. In the face of this competition, Ryanair’s losses on the Manchester route rose alarmingly to IR£700,000. In April that year, Eugene O’Neil, who became Chief Executive within a year of the airline’s formation, was removed from his post. The company released a statement citing differences with the management. Declan Ryan was named acting chief executive and both the Glasgow and Manchester routes were axed. Shortly afterwards, P J McGoldrick was brought in from a similar position at Heavy Lift Cargo Airlines (a UK-based cargo company), to take over as chief executive. On October 20, 1988, Ryanair carried its millionth passenger, Jane O’Keefe, on the flight to Dublin from London. She was presented with a golden voucher entitling her and a nominated friend free travel for life on any Ryanair route. By the end of 1988, Ryanair’s total fleet had increased to six aircraft. Losses, however, were continuing to mount, reaching IR 6 million in 1988. In September 1989, the Irish government announced a “two airline policy”, which would be valid for three years (until October 1992). The new policy was directed at benefiting both the Irish carriers, Aer Lingus and Ryanair, and eliminating the cut-throat competition between them that was harming both. The new policy ruled that the airlines would not compete on any international route and allotted them separate routes. (Aer Lingus would fly from Dublin to Paris and Manchester and Ryanair, from Dublin to Liverpool and Munich). Ryanair continued to expand and carried 100,000 passengers on the Dublin-London route in 1990. Some new routes were also added. However, the Gulf War (1990-1991) caused a general downturn in the market, and at the AGM held in November 1990, the management announced Page 3 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study losses of IR£4.5 million for 1989. The situation in 1990 looked even worse. The airline had to cut down some routes, retrench staff and shift its base from central Dublin to Dublin airport. In 1990, the losses amounted to IR£7 million. Realizing that its position was becoming increasingly weak, Ryanair refocused its activities on providing low-cost no-frills services. It also moved its London base from Luton airport to Stansted. Services to regional airports were also reorganized. In late 1991, senior management changes were announced, with McGoldrick relinquishing his position as chief executive. Patrick Murphy (Murphy), who had earlier worked for Aer Lingus, was brought in to replace him. A few weeks later, Conor Hayes was appointed chief executive and Murphy became non-executive chairman. In financial year 1991, Ryanair made its first profit of IR£300,000 since it was started in 1986. In 1992, a new livery was introduced for the planes in the fleet, with the Ryanair logo and the Irish harp painted on them in a white and blue scheme. In 1992, the airline made a profit of IR£0.8 million. Tn 1993, O’Leary, who had joined as chief operating officer in 1991, took over as CEO. In 1994, Ryanair took delivery of its first Boeing 73 7-204. By 1995, when Ryanair completed 10 years in service, it had become the biggest passenger carrier on the London-Dublin route and the largest Irish carrier on every route it operated. The airline carried a total of 2.25 million passengers in 1995. In 1997, the European Union deregulated the airline business and a number of low cost airlines (notably easyJet) offering no-frills services were set up. The deregulation of the market enabled Ryanair to open new routes to continental Europe. The same year, the airline also came out with an IPO on NASDAQ and the Dublin Stock Exchange for $500 million. With the money raised from the IPO, it ordered 45 new Boeing planes. In 2000, the airline opened Ryanair.com, an online booking site. Within three months, the site was taking over 50,000 bookings a week. By the next year, over 75 percent of the bookings were made over the internet. In 2002, Ryanair made Frankfurt-Halm (Germany) its second continental European base, after Brussels-Charleroi (Belgium). The airline also entered into a partnership with Boeing for the purchase of about 150 new aircraft over the next eight years (until 2008). By the end of 2002, the internet accounted for almost 95 percent of the tickets booked with Ryanair. By the end of 2002, the airline’s fleet had 44 aircraft. In early 2003, the airline took over Buzz, the low cost subsidiary of Dutch carrier KLM, for £15 million. Until then Ryanair had not gone in for acquisitions, but O’Leaxy said that this offer was too good to pass over. Ryanair later shut down the operations of Buzz as it undertook a massive restructuring program to make the ailing airline more profitable. In the financial year ended 31 March 2003, Ryanair had carried 15.74 million passengers and earned revenues of £842.5m. (Refer Exhibit Il). O’Leary declared that he would double the numbers of passengers to 30 million in 5 years. THE RECIPE FOR LOW FARES Ryanair followed a strategy of cost focus. The airline served a class of flyers who looked for functional and efficient service rather than luxury. It did not aim to satisfy all segments of the market. The airline’s operational policies supported its strategy of cost focus. The operational model of the airline included the following components: Simple Fleet Ryanair flew a fleet comprising entirely of Boeing 737s. This focus on standardization was a key feature in keeping the costs of the airline low, thus allowing it to offer low fares. Flying a standard fleet had the advantage of simplifying the maintenance function of the planes. The airline did not have to stock spares for different types of planes. As spares and other aircraft parts could be purchased in bulk, it resulted in economies of scale. It also reduced training requirements for the pilots and the cabin crew, as they had to only learn to operate a single type Page 4 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study of plane. This ensured interchangeability of crews, spares and furnishings between planes which made operations easier. Secondary Airports Ryanair used secondary airports. This was one of the important elements in keeping costs low. Using airports located outside city centres (many of them were former military airfields) saved time and money for the airline, as secondary airports had relatively lower landing charges. Besides, due to lower traffic, there were no delays, allowing the planes to turnaround (turnaround is the time required for a plane after landing, to be ready for its next flight) in a very short time. In exchange for bringing in passengers to airports which normally witnessed little or no traffic, Ryanair negotiated 15-20-year deals on landing fees and other agreements to the advantage of the airline. In these airports, Ryanair negotiated airport fees of as little as $1.50 per passenger (much lower than the average rate of $15 to $22 per passenger charged by Europe’s major hubs). Faster Turnarounds The turnaround time for Ryanair planes was approximately 25 minutes (the major carriers took about an hour). Most low-cost airlines based on the Southwest model (Refer Exhibit Ill) emphasized faster turnaround times to allow a plane to fly more times a day rather than spending time on the ground. This increased the efficiency of the asset. By taking about half the time of the larger airlines like British Airways (BA) or Lufthansa, Ryanair’s planes made an average of nine trips per day as against the average six of larger airlines. This made Ryanair’s planes more productive than the planes of the major carriers. Higher Productivity Ryanair used fewer employees per plane than other airlines. This increased the productivity per employee for the airline and also helped keep the wage bill low. Consequently, Ryanair’s revenue per employee was approximately 40 percent higher than that of other airlines. The simple service model also allowed Ryanair to have only two flight attendants per flight, compared to the five attendants that major carriers required. Ryanair sweated its assets. The airline flew its planes for an average 11 hours per day as against the 7 hours of BA. The pilots at Ryanair also clocked in 900 hours a year, which was 50 percent more than the pilots at BA. The airline did not keep many planes on standby to meet unforeseen contingencies. All the assets were put to work, unlike BA which usually kept about ten planes at any given time on standby. Online Sales After Ryanair.com was launched in 2000, a large number of tickets began to be booked online. By early 2003, almost 95 percent of the bookings were done through the internet. This allowed the airline to make the booking process cheaper as transaction costs came down considerably. The benefits of lower costs were passed on to customers in the form of lower prices. Although some bookings were done over the telephone and some through agents, the internet brought in the major part of business. So, the airline decided to slash the commissions to agents from 7.5 percent to 5 percent. Analysts estimated that bookings over the internet saved the airline about $6 million a year on average. No Freebies Like other discount airlines, Ryanair did not serve food or drinks on its flights. Snacks however, could be purchased on the airline. Unlike Southwest, which served drinks and light snacks, Ryanair even charged for water on the flights (a bottle of water cost about $3). Analysts said that Ryanair transformed a cost into a revenue opportunity, as it not only eliminated all expenses on food (which formed a major portion of the expenditure per passenger), but also made additional revenues through the sale of food and drinks. According to a published report Page 5 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study of the airline, Ryanair saved $50,000 a year, simply by not serving ice on its flights. None of the services provided by the airline were free either. Baggage check-in cost the passenger according to the amount of baggage carried. It meant that users paid for what they needed and didn’t pay for anything they didn’t need. Since Ryanair charged for all the optional parts of a flight, it was able to fix the basic ticket price very low. Volumes What was distinctive about Ryanair was its focus on filling its planes to capacity. If tickets did not get sold at a high price, it tried to sell them by lowering prices. It realized that it was more profitable for it to fly its planes full at lowered ticket prices rather than half-empty at its standard rates, as the unit cost of flying a person came down. Besides, since Ryanair charged for all additional services like food and baggage, it stood to profit even if the ticket was sold at a huge discount. Simplified Operations The airline did not assign seat numbers; this simplified the ticketing and administration processes. It helped the airline save time as it ensured that passengers came to the airport on time to be able to sit together or get seats of their choice on the plane. The decision to fly short and medium haul point-to-point7 flights also enabled the airline to work with a smaller number of personnel than it would have required if it adopted the more complicated hub-and-spoke system8. Transfer of baggage and people from one plane to another is generally considered a vulnerable area for airlines. Flying point-to-point avoided the need for any kind of transfer, thus keeping operations simple and inexpensive. Ryanair had very low operating costs. The $50 average cost of a Ryanair ticket could be broken down into approximately $35 operating costs and $15 profit. Thirty-five dollars as operating cost per passenger was low by any standards. Partnering Ryanair entered into partnerships and agreements with car rental companies and hotels so that it could earn commissions by selling these products to passengers. These commissions bridged the gap between the airline’s cost and profit, which allowed it to sell its tickets for very low prices. Ryanair viewed each passenger as an opportunity to make money in more ways than just transporting them somewhere by plane. By charging them for additional services and earning commissions through them, the airline could constantly drop ticket prices. Ryanair.com also hooked up with hotel chains, car-rental companies, life insurers, and mobile-phone companies to expand the web site’s range of offerings. RYANAIR’S PUBLICITY Ryanair had a publicity program, which, though sometimes unconventional, nearly always achieved its aim. The ‘attack’ on easyJet was one of the typical publicity exercises of Ryanair. The CEO of an airline blatantly waging war against another airline was a topic guaranteed to generate publicity, and Ryanair leveraged the publicity by bringing it to the notice of the public that easyJet’s fares were much higher than those of Ryanair. One ad released by the airline featured the Pope whispering into a nun’s ear. Many people felt the ad had gone too far and was in bad taste. The Vatican even sent out a press release accusing the airline of insulting the Pope. The release attracted so much attention that it got reported in newspapers as far away as India, and generated a great deal of free publicity. “I thought I died and went to heaven,” said O’Leary9. Added David Bonderman, the chairman of Ryanair, “It’s hard to think of another CEO of a company with a $4 billion market cap who would run those ads. They accomplished everything he set out to do and more.” 10 Page 6 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study Ryanair also often released ads comparing its prices to competitors’ prices. In 2001, it was involved in a controversy with BA for claiming through an ad that BA’s fares were five times higher than those of Ryanair. BA complained to the Advertising Standards Authority that Ryanair was exaggerating the situation and that the fares were, in fact only about three times higher. The advertising standards authority asked Ryanair to withdraw the ads and behave more responsibly in the future. RYANAIR’S COMPETITIVE POSITION Being the oldest low-cost carrier in Europe, Ryanair had some advantages over its competitors. For one thing, it had the advantage of experience, and secondly, its brand enjoyed good recognition. However, after the deregulation of air travel in Europe in the late 1990s, a number of startup airlines came up in the low-cost market. Notable among the competitors was easyJet, the discount airline set up in 1995 by Greek shipping magnate, Stelios Haji-Iaonnou. EasyJet was based in London’s Luton airport and competed on some of the same routes as Ryanair. In 2002, with the takeover of Go, easyJet beat Ryanair to the top position as the biggest low-cost airline in Europe. O’Leary declared that Ryanair would soon bounce back to reclaim its number one position. Although Ryanair and easyJet both operated in the low-cost segment and had similar operational models, there were some inherent differences between the two airlines. Firstly, Ryanair made a major portion of its profits by flying to secondary airports which were a long distance away from the main cities. For instance, the destination advertised as Frankfurt actually flew to Hahn, 60 miles away from the main city. A trip to Paris meant a flight to Beauvais, 43 miles north of the city, where the terminal looked like a bus depot and the baggage handlers were local firemen. The claimed flight to Copenhagen in Denmark actually landed in Malmo in Sweden. Flying to secondary airports gave Ryanair a cost advantage, but put passengers to a lot of trouble as they had to seek other forms of conveyance from the place of landing to their final destination. This resulted in a lot of delay as well as additional expenses for the passengers. Analysts said that, while leisure travellers may not really mind having to put up with additional travel, business travellers would not appreciate the inconvenience. This might put them off Ryanair. In contrast, easyJet flew to main destination airports around Europe, which made it the favourite of business travellers or people who were pressed for time. Not flying to main destination airports did not affect the market for Ryanair too much, because, unlike easyJet which sought to serve leisure as well as business markets, Ryanair only targeted leisure travellers. Additionally, analysts said that flying to main destination airports could affect easyJet adversely, because the major carriers which also flew there had begun to defend their positions against low-cost airlines aggressively. The increased aggressiveness of major carriers, who had more resources than low-cost airlines as well as more governmental support, could lead to the withdrawal of easyJet from those airports. Thus, there appeared some doubt as to whether easyJet would be able to withstand the intense competition from flag carriers. Secondly, Ryanair flew older planes than easylet. Where easyJet emphasized passenger safety by buying and flying new planes, Ryanair had some planes in its fleet which were over 20 years old. The average age of the easyJet fleet was three years, while the average age of Ryanair’s fleet was about 15 years. The founder of easyJet, Stelios Haji-Ioannou, publicly expressed doubts about Ryanair’s use of 20-year-old aircraft on some of its routes, pointing out that though they flattered profits in the short term, they put the future of the airline at risk in the event of an accident. In response, O’Leary said that easyJet was only trying to harm its rival’s reputation. He pointed out that Ryanair had an unblemished safety record in the eighteen years that it had been in operation. Nevertheless it was clear that a single airline accident (even in another Page 7 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study airline) could make passengers think twice about an airline with an older fleet. Realizing this, Ryanair had already begun phasing out its older aircraft as it purchased new ones. In terms of price however, Ryanair had a distinct advantage over easyJet; easyJet’s fares were almost 60-70 percent higher than those of Ryanair. Ryanair’s lowest fare, on flights between Glasgow’s Prestwick and London’s Stansted was $71, round-trip, while easyJet’s round-trip flight between Glasgow International and London’s Luton was $123. Ryanair’s average fares in 2002 were 30% cheaper than easyJet, and its unit costs were 80% less. Ryanair also had a better punctuality record than easyJet, taking off and landing on time more often than its rival (Refer Exhibit IV for punctuality statistics of early 2003). To steal customers from easyJet, Ryanair announced that it would lower fares 5% a year for the foreseeable future. O’Leary believed that he could launch a new price war and still stay highly profitable, mainly because of the profitable agreements he had with the airports. Ryanair also got a huge discount from plane manufacturer Boeing for the purchase of new planes. Boeing offered Ryanair this discount in order to be able to beat competitor Airbus in the European market. Ireland, where Ryanair was based, was also eligible for US aircraft subsidies as it did not manufacture aircraft domestically. This helped the airline substantially in terms of price. In 1998, the airline ordered 25 737-800 planes for about $30 million each ($15 million below the list price) from Boeing, when it was engaged in a price war with Airbus Industrie. In addition to this, easyJet’s break-even load factor (the percentage of total available seats to be sold each month to break even) was 71 percent compared to Ryanair’s 53 percent. This meant that easyJet needed more passengers than Ryanair to break even. The profits of easyJet were correspondingly lower. Ryanair’s 27% operating margin (ratio of operating income to sales revenue) was also higher than British Airways 3.8%, easyJet’s 8.7%, and the 8.6% of Southwest Airlines. Ryanair had a built-up cash pile of $1 billion and its $5 billion market capitalization exceeded that of BA, Lufthansa 11 and Air France. O’Leary believed that his biggest advantage was that Ryanair did not compete head-on with Europe’s biggest carriers. It targeted the discount market which the majors shunned in favor of the business-class traveller. “These [low-cost] companies are opening up new segments of the market without really taking clients from the regular carriers,” said Air France CEO Jean-Cyril Spinetta12. 48% of Ryanair’s passengers were budget-conscious leisure travellers who did not care about luxury and only wanted the lowest possible fares. No other low-cost airline managed to replicate Ryanair’s results. According to analysts, its “cost per available seat mile” (the yardstick used by the airline industry to measure costs) was 30% lower than the average for Europe’s major airlines, and its productivity - as measured by the number of passengers per employee - was 40% higher. As a result, Ryanair could break even when its planes were just over half-full. With the acquisition of Go, easyJet may have become the bigger low cost airline (with 19 million passengers in 2002 to Ryanair’s 16 million), but Ryanair was in a better financial position, with net incomes higher than those of easyJet, from lower revenues. (Refer Exhibit V). easyJet had reported losses for the first quarter of 2003, due to the acquisition costs of Go for which it paid a phenomenal £374 million, however, Ryanair had made a profit, in spite of the acquisition of Buzz. Analysts wondered how Ryanair would fare if there was new competition in the European airline market. O’Leary however, felt that there was unlikely to be any major new competition. ‘There are huge barriers to entry now, and none of the new airlines are going to be able to find a price point below Ryanair or easyJet,” he said. He also said that Ryanair was poised to become the counterpart of Southwest Airlines in Europe, while easyJet was imitating the strategy of JetBlue, which flew to major airports and did not cut costs quite as drastically as Southwest. “Air Page 8 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study transport is just a glorified bus operation. You get on, you want to get there quickly, with the least amount of delays, and cheaply.” said O’Leary. He believed that those who could provide the fastest and cheapest means of transport were likely to survive in the long run. Notes 1 Kerry Capell, Carlos Tromben, William Echikson, Wendy Zeilner, “Renegade Ryanair”, Business Week, May 14, 2001. 2 Keny Capell, Carlos Tromben, William Echikson, Wendy Zeliner, “Renegade Ryanair”, Business Week, May 14, 2001. 3 ‘ The Life of Ryan”, www.easyprotest2.com. 4 www.ryanair.com. 5 EasyJet is a low cost airline based in London. It was set up by Stelios Haji-Ioannou, a Greek shipping magnate. 6 GPA was set up in 1975 as an aircraft leasing company. Tony Ryan is a founder member of GPA. 7 In the point-to-point system the planes have a simple flight route and flies from the origin to destination. 8 A hub-and-spoke system uses a strategically located airport (the hub) as a passenger exchange point for flights to and from outlying towns and cities (the spokes). 9 Keny Capell, Carlos Tromben, William Echikson, Wendy Zeilner, “Renegade Ryanair”, Business Week, May 14, 2001 10 Kerry Capell, Carlos Tromben, William Echikson, Wendy Zeilner, “Renegade Ryanair”, Business Week, May 14,2001 11 The national airline of Germany 12 Kerry Capell, Carlos Tromben, William Echikson, Wendy Zellner, ‘Renegade Ryanair”, Business Week, May 14, 2001 Page 9 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study EXHIBIT I LOW COST AIRLINES IN EUROPE In the mid-1990s, after the European Union deregulated air travel, a number of upstart airlines came up, providing no-frills travel around Europe. easyJet, Ryanair, Buzz13, bmibaby14 and Go15 were some of the airlines fighting for airspace. Low-cost airlines had a large market in Europe because the number of people travelling between the different countries increased after the formation of the European Union. Train travel was slow and expensive. Therefore, people looked to airlines to meet their travel needs. Low-cost airlines identified the business opportunity and offered tickets which were about half the price of a train ticket. They thrived on volumes rather than profit margins. So successful were the low-cost airlines that some of the national carriers also set up low-cost subsidiaries. (Go was set up by British Airways, Buzz by Dutch carrier KLM, and bmibaby by British Midlands Airlines.) The low-cost airline industry was characterized by high competition. The standard of service of all these airlines was almost the same and they competed within the same markets. This made rivalry intense. In the early 2000s, the low-cost airline industry began getting consolidated, with Go being taken over by easyJet and Ryanair taking over Buzz. EasyJet and Ryanair became the biggest low-cost airlines in Europe. Ryanair had the advantage of age and experience as it had been set up ten years before easyJet. But easyJet, with its fleet of new planes and practice of flying to airports in the main cities (unlike Ryanair) overtook Ryanair to the top position in 2002. Source: Compiled from various sources. 13 low-cost subsidiary of Dutch carrier, KLM. 14 low-cost subsidiary of British Midland airlines. 15 was the low-cost subsidiary of British Airways. Page 10 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study EXHIBIT Ill SOUTHWEST AIRLINES Southwest Airlines (Southwest) was started in 1967 by Rollin King, John Parker and Herb Kelleher. King, an entrepreneur from San Antonio, Texas, owned a small commuter air service. Parker was his banker, while Kelleher was the legal advisor to King’s air service. The airline aimed to provide the best service with the lowest fares for short-haul, frequent-flying and pointto-point ‘non-interlining’16 travellers. Over 30 years of operation, Southwest became one of the most successful airlines in the US. In fact, it was the only airline that was able to stay profitable even after the September 11 terrorist attacks on the USA in 2001. The success of Southwest spawned a number of other airlines which tried to imitate Southwest’s model of providing low-cost and high quality services. Some of the components of the Southwest operational model are given below. 1. Low fares: Southwest offered one of the simplest and most inexpensive fare structures in the US. The low fares were made possible by adopting a number of techniques which brought down the operating expenses of the airline. The airline also had a frequent flyer program which gave a free round trip to a customer who purchased eight round trips on a particular route. 2. Customer focus: Southwest geared its operations to the needs of its customers. It therefore developed a flight schedule with frequent departures to meet the customers’ need for flexibility. Airports were also conveniently located near city centers to make flying more convenient. 3. Standard Fleet: To simplify operations, Southwest used only one type of aircraft — the Boeing 737, in an all coach configuration. This simplified the maintenance function and resulted in economies of scale due to bulk purchase of spares and other parts. 4. Secondary airports: Southwest flew into less congested, secondary airports. This helped negotiate better landing terms and also save time. This also allowed it to turn around the planes faster. 5. Turnarounds: Southwest had one of the fastest turnaround records of all airlines. It turned around planes in about 15 minutes, which was a quarter of the time taken by major airlines. This allowed better utilization of the fleet. 6. Point-to-point flights: Southwest flew point-to-point, short haul flights, which made operations simple and inexpensive, and allowed the airline to save time. It could also operate with fewer staff than airlines that adopted a hub-and-spoke system. 7. No food: Southwest pioneered the concept of not serving food on short haul flights. Instead of meals, the airline served drinks and light snacks. On the shortest flights, even these were eliminated. This helped the airline save a considerable amount of money and consequently keep fares low. Source: Compiled from various sources 16 Southwest did not arrange connections with other airlines; passengers transported their own luggage to recheck themselves onto connecting airlines. Page 11 of 12 Operations Management Staffordshire University Business School BSB20124-7 Ryanir Case Study Page 12 of 12