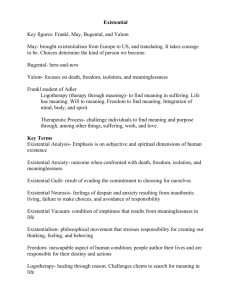

EXISTENTIAL - Dr. Paul TP Wong

advertisement