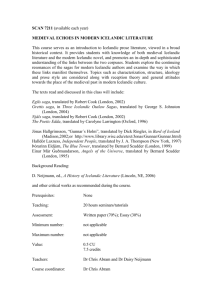

Cultural Paternity in the Flateyjarbók Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar

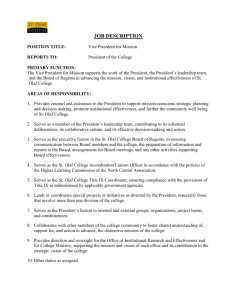

advertisement