Knight v The Queen & Cassidy v The Queen

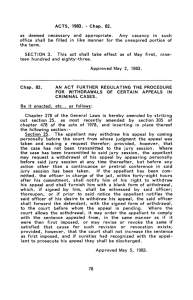

advertisement