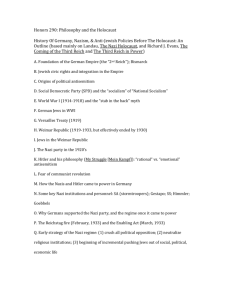

The Jewish Holocaust - A Comprehensive Introduction

advertisement