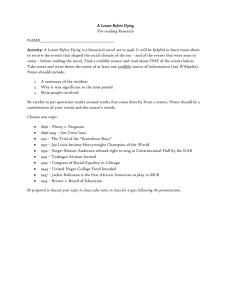

209 Assignment Sequence A

advertisement

English 209: Introduction to Fiction Fall 2009 Instructor: Office: Office Phone: Email: Office Hours: Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. —Pablo Picasso Fiction reveals truth that reality obscures. —Ralph Waldo Emerson There are four overall goals for English courses at this level: 1) Maintain and continue to improve the abilities gained in English 101 and 102 2) Develop multiple strategies of reading 3) Write about texts in ways appropriate to the genre or theme of the course 4) Demonstrate the ability to think clearly about language, texts, and experience This particular course has three additional objectives: 1) To explore, discuss, and interrogate—as individuals and citizens—our language’s behavior 2) To familiarize you with the elements of fiction writing 3) To introduce you to a wide variety, albeit limited, of English-language works of fiction Department Course Description: In-depth reading of and writing about prose fiction with emphasis on critical analysis of a variety of narrative types from different historical periods. An Alternative Description: Today we stand at a turning point in narrative history and in the history of narrative. The methods by which we shape and determine what qualifies as history and the mediums through which we receive its messages have been radically transformed. For instance, consider how to define the contents of youtube. Is “panda sneeze” a work of art? Is “Christian the Lion” an historical artifact? A music video? Is “Battle at Kruger” part of a diary? Are these movies? We might say, dismissively, “they’re just videos,” but, in doing so, fail to acknowledge the new possibilities—even as we’re transformed by them—the form presents us. The always somewhat uncertain or incomplete boundary dividing socalled fact, from fiction, quote-unquote, is strategically blurred to such an extreme degree in our culture, that to bother with making the distinction at all seems increasingly pointless and exhausting. In many cases, those who preoccupy themselves with drawing such lines appear to be the most egregious offenders of their decorum. Our public officials, for example, are not only political actors, more and more frequently, they’re dramatic actors as well. Even our food is largely McFood—fictitious, fabricated, “made up.” Still, our personal and collective dependency on language is very real, and language is itself a living thing, harboring and projecting realities its speakers might otherwise try to suppress. Indeed, when you open your mouth, “you put your business in the street,” James Baldwin informs us: “You have confessed your parents, your youth, your school, your salary, your self-esteem, and, alas, your future.” It’s a fact that America, as a nation, came in to being in the same century as the novel, but this coincidence has evolving significance. Questions of cultural transfer and transmission, of representation and appropriation, will guide us through this course. How do our short stories and novels absorb, impress, and reveal us? What does it mean, and what good does it do, to have a national literature, a literary canon, as it’s called (the Latin word for “rule”)? What is literature, anyway? Let alone “American literature”—how do we define that? And why are we here to read it? In fact, what does it mean, in an age of digital reproduction, of twitter and emoticons, to read at all, or to tell a story? Required Materials: ) Charters, Anne, ed. The Story and Its Writer: An Introduction to Short Fiction. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007. ) Faulkner, William. As I Lay Dying. New York: Vintage International, 1930. ) McCarthy, Cormac. Blood Meridian, Or the Evening Redness in the West. New York: Vintage International, 1985. 1 ) Toomer, Jean. Cane. New York: Liveright, 1923. ) Saunders, George. CivilWarLand in Bad Decline. New York: Penguin Books, 1996. ) Zurawski, Magdelena. The Bruise. Tuscaloosa: FC2, 2008. ) Composition & Literature, 2008-2009 (required for 101, 102, and all 200-level ENGL courses) Grading: Quizzes, Homework, & In-Class Writings Response Papers Paper #1 Paper #2 Final 10% 20% 20% 25% 25% Description of Assignments: NO EMAILED ASSIGNMENTS. ALL ASSIGNMENTS MUST BE TYPED. Papers: There are two papers in the course. The specific assignment and criteria for each paper will be made clear well before it’s due. Each paper should represent your best work, including attention to spelling and punctuation, organization, and proof-reading. Final: The final assignment will consist of short essays (shorter than the papers), and short answer questions covering the elements of fiction, the application of critical lenses, the identification of literary terms, etc. Daily Work: There will be a short response paper over each novel. These serve two purposes: a) to hone reading and critical thinking skills and to improve analytical writing; b) to enable and enhance class discussion. These assignments are due in class the day that we discuss the work about which you’ve written. Quizzes: Short quizzes covering vocabulary or simple features of the assigned stories/chapters will begin many our meetings. These might be replaced by a short writing. You’ll drop a couple of the lowest scores. Policies and Expectations: COME TO CLASS PREPARED AND READY TO CONTRIBUTE. DON’T USE YOUR PHONE. Late Work: All major paper assignments, including the final, must be completed in order to pass the course. Late assignments will be counted off half of a letter grade per class day. Religious holidays and university-sanctioned events (these are administratively-defined) are exceptions to these policies, but please let me know ahead of time. If you have questions about this, ask me. Attendance: Come to class prepared. After six unexcused absences (excepting, again, religious holidays, universitysanctioned events, medical problems with verification, etc.), your overall grade will be lowered one letter-grade per day for every subsequent absence. If there’s a crisis, let me know. ESL and Students with Disabilities: Students who speak English as a second language and experience any difficulty fulfilling the requirements should speak to me as soon as possible. Likewise, any student with a disability that interferes with any of the requirements of the course should contact me as soon as possible. Academic Dishonesty: Don’t plagiarize. The Student Handbook, as well as the English Department’s description in Composition and Literature, can inform you of KU’s policy; mine follows suit. Withdrawing from the Course: The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Undergraduate Services (CLAS) sends out email messages concerning the drop deadlines. This semester the guidelines for withdrawing have changed, so be sure to take notice. 2 INTRO TO FICTION—SCHEDULE OF CLASSES ***When reading short stories from The Story and Its Writer (SIW), you should ALWAYS read the “Related Commentary” (RC), unless otherwise indicated by this schedule. ***Readings are listed next to the day on which they are due. AUGUST R 20: Introduction T 25: What is literature?: B. Anderson, 22–46 (handout); T. Eagleton, 1–16 (handout); “A Brief History of the Short Story,” 1758–1767 (SIW); W. Grue, “Ordeal by cheque” (handout) [THE ELEMENTS OF FICTION & THE SHORT STORY] R 27: Introduction to elements of fiction: “The Elements of Fiction,” 1742–1757 (SIW); R. Ellison, “Battle Royal,” 371-381 (SIW) & RC (1441); W. Allen, “The Kugelmass Episode,” 21–30 (SIW) SEPTEMBER T 1: Point of View: E. Hemingway, “Indian Camp,” (handout); D.F. Wallace, “Incarnations of Burned Children,” 1313–1316 (SIW); DUE: Point of View Response R 3: Setting: G. Saunders, “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” 3–26 (CWLBD) T 15: Imagery: V. Woolf, “Kew Gardens,” 1361–1366 (SIW) & RC (1493); G.G. Marquez, “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings,” 462–467 (SIW) & RC (1453); DUE: Setting or Imagery response R 17: Plot/Structure: F. O’Connor, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” 1030–1041 (SIW) & RC (1619; 1641); G. Stein, “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene,” 1198–1202 (SIW) & RC (1405) T 22: Dialogue: R. Carver, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” 187–196 (SIW) & RC (1557; 1593); DUE: Plot/Structure or Dialogue response R 24: Character: F. Kafka, “A Hunger Artist,” 681–686 (SIW) & RC (1421; 1694); J. Updike, “A&P,” 1282–1287 (SIW) T 29: Style & Theme: H. Melville, “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” 846–873 (SIW) & RC 1503; K. Vonnegut, “Harrison Bergeron,” 1300–1305 (SIW); DUE: Character or Style & Theme response [THE MODERNIST NOVEL] October R 1: Paper Prep: “Writing About Short Stories,” 1768–1797 (SIW) T 6: PAPER #1 DUE; Film TBA R 8: J. Toomer, Cane (1–55) T 13: Cane (56–116) R 15: Fall Break T 20: W. Faulkner, As I Lay Dying (3–122); DUE: Cane response R 22: As I Lay Dying (123–193) T 27: As I Lay Dying (194–261) R 29: Critical Lenses: “Literary Theory and Critical Perspectives,” 1798–1805 (SIW) & additional readings (TBA); DUE: As I Lay Dying response [THE POSTMODERN NOVEL] November T 3: G. Saunders, “Bounty,” 88–179 (CWLBD) 3 R 5: “The 400-Pound CEO,” 45–64 (CWLBD) T 10: PAPER #2 DUE; Film TBA R 12: C. McCarthy, Blood Meridian, 3–54 T 17: Blood Meridian, 55–135 R 19: Blood Meridian, 136–185 T 24: Blood Meridian, 186–259 R 26: Thanksgiving December T 1: Blood Meridian, 260–335; DUE: Blood Meridian response R 3: M. Zurawski, The Bruise, 10–69 T 8: The Bruise, 70–141 R 10: The Bruise, 142–174; DUE: The Bruise response We’ll discuss the due date for final exam/paper as the end of the semester approaches. 4 ENGL 209: Introduction to Fiction Paper #1 DUE: Tuesday, September 6, 2009 Goal & General Requirements: Write a four to six page analytical paper in response to one of the prompts below. The paper should exhibit your best work: thoughtful and serious consideration and articulation of your ideas about the story/ies, as well as the appropriate attention paid to correct spelling, punctuation, and other structural matters of academic writing (e.g., transitions, tone, formatting, etc). The following represent the three most important elements your paper should contain: 1) A coherent, well-developed ARGUMENT (i.e. an overall assertion with which another reader/writer could disagree, and to which they could propose a counter argument) 2) SPECIFIC QUOTATIONS (from the story/ies) that illustrate and support your assertions 3) ANALYSIS of the specific language of the quotes **[Analysis discusses not simply what the text says, but how it says it. How is the specific language of this or that quote significant to your overall argument—what kind of internal orders are created by the specific language of your story? What biases, beliefs, attitudes, etc. construct and inform the story’s language?] IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO WRITE OVER A STORY THAT IS NOT INCLUDED HERE, YOU MUST DISCUSS YOUR CHOICE WITH ME BEFOREHAND. Prompt/s: In cultural studies, the notion of “performance” addresses a broader spectrum of activities and behaviors than our daily discourse might suggest. Here is an excerpt from Key Concepts in Communication and Cultural Studies, in which John Hartley defines “performance” in this regard: [Performance] encompasses both institutionalized, professional performances (drama, ritual), and non-psychologistic approach to individual people’s self-presentation and interaction. … First, the term has been applied not only to what actors and other professionals do but also to the ‘performance’ of unrehearsed cultural practices in everyday life, the actions of audiences, spectators and readers not least among them. … Second, the concept of performance directs the analyst’s attention not to the internal psychological state or even the behavior of a given player, but to formal, rule-governed actions which are appropriate to the given performative genre. If you start looking at ordinary encounters in this way, from doctor–patient interviews to telephone calls, it is clear that there are performative protocols in play that require skill and creativity in the manipulation of space, movement, voice, timing, turntaking, gesture, costume, and the rest of the repertoire of enactment. Building off of this concept, explore and discuss “performance” as it relates to one of the three short stories below. 1) “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” As the story unfolds, how do the roles that O’Connor’s characters (the grandmother, the father, the children, the Misfit, etc) find themselves performing differ from those they intend, or desire, to perform? How do the performances of the various characters in some ways meet, and in others disrupt, our expectations? Explore the tension that develops between the roles that characters believe 5 themselves to inhabit, and those their experiences force upon them. Are there identifiable institutions and/or traditions discussed in the story that determine the nature of these performances? Does the phrase “a good man” denote a certain kind of performance? Do hardened notions of performance in any way permit, even encourage, the horrific outcome of the story? 2) “A&P” After he quits his grocery job at the end of the story, Sammy admits to us: “…my stomach kind of fell as I felt how hard the world was going to be to me hereafter.” How do you think he means this—is he being melodramatic? Is he more accurate than he realizes? Do you read Sammy’s decision to quit his job as noble or impulsive? How do the obligations of his job conflict with the image Sammy wishes to project of himself? How do social categories of masculinity and class affect Sammy’s behavior? Considering we hear the story from his perspective, how aware do you think Sammy is of these societal influences/pressures? 3) “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” and/or “The Kugelmass Episode” Study the use of language in these stories, examine the conversations between characters, and catalogue the familiar or “stock” phrases each employs. What are the possible sources of this rhetoric? How is the notion of performance at work here? How does the dialogue (as well as the narration) relate to, or come into being as a consequence of, the specific situations and relationships in which the characters find themselves? How much communication is really taking place in these stories? Are there larger societal trends that the story, in its use of this mode of talk, is commenting on? 6 ENGL 209: Introduction to Fiction Paper #2 DUE: Thursday, November 19, 2009 Goal & General Requirements: Write a 4–6 page analytical paper, or a 3 page creative paper (accompanied by a 2 page explanatory statement) in response to one of the prompts below. The paper should exhibit your best work: thoughtful and serious consideration and articulation of your ideas about the novel, as well as the appropriate attention paid to correct spelling, punctuation, and other structural matters of academic writing (e.g., transitions, tone, formatting, etc). This paper must also contain at least one scholarly, critical source. Your essay should actively and dynamically engage this source—i.e. by positioning your argument (as a counter-argument, say) with regard to your source’s central assertions; or by employing the source’s central argument as an interpretative model for your own investigation; etc. Your paper must correctly cite (both in-text and in a bibliography) this outside source, as well as any quotes/evidence that you include from the novel about which you’re writing. IMPORTANT: YOU PAPER SHOULD FOLLOW MLA FORMATTING GUIDELINES. • If you choose to write a creative response, you will also write a short statement discussing specific choices you’ve made. Note the following criteria: 1) How have you specifically engaged (imitated, satirized, etc) Faulkner’s style? Identify at least three specific elements and explain how you’ve applied them. 2) What other aspects of As I Lay Dying, such as imagery or theme, does your piece engage? 3) Where in the book should your chapter appear, i.e. between which chapters? Why? 4) Your explanatory writing itself should follow the criteria for analytical papers indicated in the paragraph above. • The following represent the three most important elements your analytical paper should contain: 1) ANALYSIS of the specific language of the quotes *[Analysis discusses not simply what the text says, but how it says it. How is the specific language of this or that quote significant to your overall argument? What kind of internal orders are created by the specific language of your story? What biases, beliefs, attitudes, etc. construct and inform the story’s language?] 2) SPECIFIC QUOTATIONS AND EVIDENCE (from the story/ies) that illustrate and support your assertions *[explaining how this evidence illustrates, supports, and specifically develops your assertions is the purpose of ANALYSIS] 3) A coherent, well-developed ARGUMENT (i.e. the sum of your analysis; this assertion should be developed/elaborated by the specific claims of your body paragraphs, an overall assertion with which another reader/writer could disagree, and to which they could propose a counter argument) Questions over Cane: • How do particular characters in Cane respond to, or adjust their behavior according to, the unwritten social laws of their segregated community/ies? How do these laws affect men and women differently? How do they determine the narrative methods and perspectives in the novel? • How do the prose and verse sections interact in Cane? What does each specifically supply to the mood and environment of the story? How does each form enhance the other? Can you map or decipher a logic behind their organization? What actions, themes, images link these sections? Questions over Cane and/or As I Lay Dying: 7 • What does it mean to be “whole” or complete in these novels? How does one complete a whole? What is a “whole” anyway? More/Less than the sum of its parts? Is the pun (“hole”) in “whole” significant? Interestingly, the words “whole” and “hail” are etymologically related. Look it up. Can you make any sense of this in relation to Cane or As I Lay Dying? • Silence and womanhood: detachment or resistance? Discuss. • How does time operate in the novel/s? What is time a factor of (place? age? class? gender? etc), and how do we understand its motion (linear? circular? variable? etc)? How does time influence character? How does the form of the novel manipulate time? Questions over Cane, As I Lay Dying, or Bounty (NOTE: DO NOT write about Bounty alone): • What does it mean to journey in this/these novel/s? What are the different perceptions of, and perspectives on, journeying? What are their motivations? What changes and what is changed by the these journeys? What does The Odyssey have to do with this? What do American regions have to do with this—i.e. the (American) West, the South, or the North?—or regional designations (i.e. rural vs. urban, etc)? • What is/are the effect/s of absence in this/these novel/s? How does it operate on families, lovers, even societies? Are absence and presence related? How does the absence of love, or its disfigured presence, impact character and theme? What do acts of love look like in the novel/s? Are they present at all? • What does it mean to grieve in this/these novel/s? What is grief a factor of? Is/are there (an) identifiable “grieving process” in this/these novel/s? If not, how is that lack significant? How is/are a particular character’s way/s of grieving related to that character’s expectations? Questions over As I Lay Dying: • Write a chapter from the perspective of a character (or an animal, or an inanimate object) who appears in As I Lay Dying, but from whom we do not hear directly. • Celebrated American poet, Robert Creeley once described his writerly goal to imagine the pronoun “I” in terms of the organ of the “eye”—that is, to understand “I” (the first-person pronoun) as, “a locus of experience, not a presumption of expected value.” What does Creeley mean by this? How might his notion of what constitutes “I” inform your understanding of narrative perspective in As I Lay Dying? Could that title, for instance, doubly refer to a death of “I”— that is, aside from Addie’s literal death, does the “I” in the title point to an experience that is simultaneously contained within the book and initiated outside of it (like the reader’s position, for example)? Discuss the complications and complexities, the implications and consequences, of the first person narration and perspective in the novel. • Thinking again of Creeley’s statement: as an interface between the emotional, psychological interior, and the external world, the eyes point in two seemingly opposite directions. Our eyes are themselves objects, and we use them to confirm and assess objective reality. At the same time, our eyes are “windows to the soul,” they betray internal conditions and they subjectively organize each of our singular experiences. How do eyes function in As I Lay Dying? Do they reveal, conceal, penetrate, scan, wander, etc.? How do they relate to character? • Who is the protagonist and who is the antagonist in As I Lay Dying? Drawing on specific definitions of these roles, make an argument about how and why the novel’s meaning/s change/s according to which characters one envisions playing these roles. • How does death permeate As I Lay Dying? In what ways is the novel centered around the death process? Does death have various embodiments here? What other kinds of death (figurative, symbolic, metaphorical) appear? How does death relate to ideas about permanence and impermanence in the novel? • How does death force the living to reevaluate the limits/bounds of their own being, of temporal identity in general? Different characters in As I Lay Dying struggle with questions that are at once personal and cosmic—ontological 8 questions and epistemological questions. What does it mean to exist, “to be or not to be,” for the members of the Bundren family? • Respond/Discuss: the reader of As I Lay Dying is a vulture. In what ways is this comparison apt? In considering this, one might note a number of passages either spoken by or relating to Darl—for example: “High against it they hang in narrowing circles, like the smoke, with an outward semblance of form and purpose, but with no inference of motion, progress or retrograde. We mount the wagon again where Cash lies on the box, the jagged shards of cement cracked about his leg. The shabby mules droop rattling and clanking down the hill” (227). • How do emotional pressures in As I Lay Dying influence, compel, or distort the language of its characters? The gaps existing between speech, thought, and action in the novel make certain of its sections difficult to read, and obscure or subvert many of its central developments in plot. How do fragmentation and ambiguity construct our notions of action, character, and environment? How might these concepts also invoke the activity of reading itself (i.e. is reading acting? is it thinking? is it active? is it passive? etc.)? • Many characters in As I Lay Dying are constantly paired with a specific object, or objects. Discuss these pairings. What do they tell us about character? What do they imply overall about what it means to be human in this novel? • What does the body signify in As I Lay Dying? How does the body operate as a record of experience—a record that one might read, like a book? Is the body a symbol, is it a metaphor? For what? How do we come to know the characters in the book through the descriptions of their bodies? • Are there noble characters in As I Lay Dying? Does the novel contain actions or decisions that consider to be noble? Is the question of nobility inseparable from the question of intent? What does it depend upon? Is nobility a mutually exclusive mode for members of the Bundren family—that is, if one sees Jewel as a noble character, is it possible to see Darl that way too? Or vice versa? • As Darl watches Jewel race to save the inhabitants of Gillespie’s burning barn, he describes the scene in twodimensional terms: “…[Jewel] springs out like a flat figure cut leanly from tin against an abrupt and soundless explosion as the whole loft of the barn takes fire at once, as though it had been stuffed with powder. The front, the conical façade with the square orifice of doorway broken only by the square squat shape of the coffin on the sawhorses like a cubistic bug, comes into relief.” First published in 1930, As I Lay Dying sits at the tail end of the modernist movement known as Cubism, which The Oxford American Dictionary defines as, “an early 20th-century style and movement in art, esp. painting, in which perspective with a single viewpoint was abandoned and use was made of simple geometric shapes, interlocking planes, and, later, collage.” Discuss As I Lay Dying as a cubist work of art. 9 QUESTIONS FOR THE OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY 1 Respond briefly to each: 1. Outline the structure (categories and their arrangement) of an entry. 2. Sphinx. What are its plurals? Was the English word first applied to the Greek or the Egyptian creature? In what century was “spynx” used? 3. Contrary (verb). What does the symbol in front of the main entry mean? How was it sometimes applied in the 14th and 15th centuries? When is the last recorded usage? Next to the last? 4. Uncouth. What is the earliest English sense of the word? In what century is the modern sense “uncomely, awkward” first recorded? In Robert Burns’ poem “Address to the UncoGuid,” explain the meaning and origin of “unco.” 5. Which of the following phrases seems most natural to you? a) an enthusiasm which was nothing short of passion b) a passion which was nothing short of enthusiasm Use the OED to explain how your preference and earlier preference might differ. 6. Secret. What did Shakespeare mean by it when he wrote, “How now you secret, black, and midnight Hags? What is it you do?” Is that meaning a current one? 7. Legend. What is the etymological sense of the word (meaning in ultimate source language)? What is its earliest recorded meaning in English? In what century did the sense “unauthentic or non-historical story” appear? 8. Gossip. What was its original construction (i.e. spelling)? Its original meaning? When did the meaning shift first begin? What is the latest citation for the older meaning? 9. Error. In what century did the current spelling prevail? What sense of the word is likely in Tennyson’s “The damsel’s headlong error thro’ the wood”? How did the word acquire that sense? 1 You can find the OED on the KULibraries homepage by clicking on the “Articles and Databases” link, and scrolling through the “O” list of databases. 10 SHORT WRITINGS OVER THE “ELEMENTS OF FICTION” IN SHORT STORIES: For each of the following assignments, you are to write a two-page essay. However, the main objective of these papers is not to assert and develop a specific thesis through an organized discussion of the short story, but rather to hone our critical/analytical skills. Thus, you should disregard formal introductions and conclusions, and, instead, focus on dissecting specific language from the text. How does this specific language make meaning? How do individual parts of the text incorporate, reflect, inhere, etc., the text as a whole? Generating particular ideas about language—as opposed to arranging and organizing those ideas in the form of a coherent argument—is the priority of these assignments. Point of View (due 9/1/09): After reading the “Point of View” section in the “Elements of Fiction” appendix (SIW), discuss, citing specific moments in the text, how the point of view in “Indian Camp” or affects the story overall. From whose point of view do we view the action of the story? How does the point of view construct our impression of Nick’s father? What about his uncle? And the “Indians”? How do the limitations our narrator’s point of view manipulate how we view what the pregnant woman is going through? Remember, again, to point to specific language in the story. Plot/Structure (due 9/22/09): After reading the “Plot/Structure” section in the “Elements of Fiction” appendix (SIW), discuss, citing specific moments in the text, how the plot and structure of “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” or “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene” affect the stories overall. Does the story’s structure conform to the stages of narrative development Charters describes—e.g. exposition, climax, etc.? If not, how does it manipulate these stages, and to what effect? How does the structure of the story illuminate, enact, or direct our attention to, certain themes, situations, activities, behaviors, processes, etc. that occur elsewhere in the text? Remember to refer to specific language in the text in order to support your claims. Setting/Imagery (due 9/15/09): After reading the “Setting” and “Imagery” sections in the “Elements of Fiction” appendix (SIW), discuss, citing specific moments in the text, how the setting or imagery of “Kew Gardens” or “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” affect the stories overall. Does the setting reflect or make manifest certain interior aspects of the story’s characters? How is the setting of the story a character in and of itself—i.e. has agency, influences behavior, etc. How does imagery complement the actions of the characters? How does imagery link different sections of the story? Remember to refer to specific language in the text to support your claims. Character/Style (9/29/09): After reading the “Character” and “Style” sections in the “Elements of Fiction” appendix (SIW), discuss, citing specific moments in the text, how character or stylistic choices in “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” “A&P,” or “Bartleby, the Scrivener” affect the stories overall. Who is the protagonist? With what does the protagonist struggle? How do the actions and desires of characters in the story reveal their attitudes, beliefs, or biases? Which characters are dynamic, which static, which a bit of both? How does the style in which the story is told propel or enact larger concerns or trends in the story? Can we distinguish between characters by the way 11 (that is, the style) in which they talk? How does the form of the story reflect its content? Remember to refer to specific language in the text to support your claims. 12 ENGL 209: Introduction to Fiction Final Paper DUE: Friday, December 18, 2009, 5:00pm @ Wescoe Goal & General Requirements: Write a 4–6 page analytical/persuasive paper, or a 3 page creative paper (accompanied by a 1½ page explanatory statement) in response to one of the prompts below. The paper should exhibit your best work: thoughtful and serious consideration and articulation of your ideas about the novel, as well as the appropriate attention paid to correct spelling, punctuation, and other structural matters of academic writing (e.g., transitions, tone, formatting, etc). • If you choose to write a creative response (see the last two prompts) you will also write a short statement regarding the specific choices you’ve made regarding the following criteria: 1) How have you addressed (imitated, satirized, etc.) the author’s style? To which other chapters, events in the book does your addition refer? Where does it fit in? 2) What other literary devices and characteristics of the novel, such as its imagery or one of its themes, does your piece engage? 3) Any other significant features of your chapter, or the process that generated it, that you wish to highlight 4) Your explanatory writing itself should follow the criteria for analytical papers indicated in the paragraph above. • The following represent the three most important elements your persuasive or explanatory paper should contain: 1) ANALYSIS of the specific language of the quotes **[Analysis discusses not simply what the text says, but how it says it. How is the specific language of this or that quote significant to your overall argument—what kind of internal orders are created by the specific language of your story? What biases, beliefs, attitudes, etc. construct and inform the story’s language?] 2) SPECIFIC QUOTATIONS AND EVIDENCE (from the story/ies) that illustrate and support your assertions 3) A coherent, well-developed ARGUMENT (i.e. an overall assertion with which another reader/writer could disagree, and to which they could propose a counter argument) Persuasive Prompts: • “To cut is to heal,” poet Michael Harper has written. Focusing on The Bruise and one other novel or short story, discuss the relationship between violence and the construction of identity. In what specific ways do injury and pain affect character development? How are these characters transformed by their injuries? • What is a “bruise,” anyway? How many different ways can you define it? What kinds of things does a bruise represent? In what ways does the bruise operate as a structural metaphor in Zurawski’s novel? How does it affect the form of the novel? Explain the bruise’s function as such. • These novels—Blood Meridian and The Bruise—are partially about being novels, or texts. They both contain characters who want to capture the “actual” world on the written page. “Men’s memories are uncertain and the past that was differs little from the past that was not,” the Judge tells the kid. How does the Judge’s sense of records (historical and otherwise), objects in the external world, and order compare and contrast with M’s sense of these things? Is every writer a judge? Do writers and judges merge under the double-meaning of the “sentence” (as grammatical unit and juridical decree), that which each authors? How does writing (the act of writing and the written word) operate in these novels? What does it signify? Does it work for preservation or elimination? And what does this mean for these novels, as “self-conscious” works? 13 • There are a few places in Blood Meridian whereat the Judge espouses his philosophy (pages: 145; 146-147; 245; 247-250; 328-331). Reread these passages and summarize/explain the Judge’s philosophy. What does it mean that his rifle is inscribed with the phrase: Et In Arcadia Ego? Then, discuss the legacy of the Judge as a kind of mythic character in America. Can you detect specific features of the Judge’s philosophy at work in contemporary events. What is “American” about the Judge? • Imagine you’re a film writer/director who has been chosen to adapt Blood Meridian to the screen. How specifically will you present this story? What parts of the book do you think are especially engaging or important for a film? Detail other choices that you would make? Would you adapt the movie to a different time? REMEMBER: You must present evidence from the book and you must explain your decisions (i.e. why they are appropriate; how they activate certain themes; etc.) • There are many objects to which M meticulously attends in The Bruise. Why does the novel that M is writing (the novel that we are reading) fixate on these things so much? Does M’s obsessive cataloguing force us to distance ourselves from the emotional pain with which M struggles, or does it bring us into more intimate, human contact with her experience and her registration of it? • What happens when M dreams? Is it easy to tell when M is dreaming and when she is awake? How is the substance of her dreams important to her character overall? What does she learn from her dreams? • Is there a logic to M’s obsessive analysis? How does this thought process affect her sense of identity? Can you present a context in which M’s thought processes can be organized? Can you present a logic for, or classify, the things she thinks about? • Compare and contrast Kit, the protagonist of Badlands, and the kid (the protagonist—I guess—of Blood Meridian). What does violence mean to each of them? How does it relate to the fabric of their characters’ otherwise? How does it affect our attachment and sympathies to these primary characters? • Discuss the landscape of Blood Meridian. How does it relate to character development? How does it articulate, or deny, the interior landscape of the characters that move over it? How does it predict/feed the outcome of the story? • What does it mean to be “real” for M? How does M define herself? Why does she so frequently use reflections and foreign objects to accomplish this? How does the sentence that she carries always in her wallet (pg. 68) relate to the development of her identity? Creative Prompt: • Ten years after her experience that concludes The Bruise, M is diagnosed with breast cancer. Write a chapter that represents M’s response to living with this disease. 14