“AP Human Geography: A Freshman

advertisement

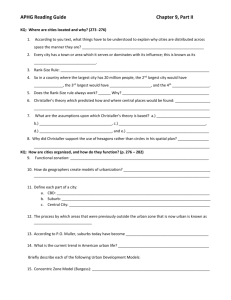

“Advanced Placement Human Geography: A Freshman-Level Course with FarReaching Benefits” Submitted Summer 2011 to partially fulfill the requirements of a Masters in Science Degree at the University of Oregon Rob Shepard September 3, 2011 ii Abstract The objective of this inquiry was to examine 1) the impact of Advanced Placement Human Geography (APHG) on student achievement and 2) the impact of placing APHG during a student’s 9th grade year. The research was gathered using data acquired from Township High School District #214 in the northwest suburbs of Chicago, Illinois. The College Board supplied quantitative data and qualitative data was gathered at Elk Grove High School using a survey. The results of the research pointed to a clear benefit for students who took the APHG exam. The benefits of taking the exam ranged from an increased performance on the AP World History exam to a belief among students that they were more prepared for the rigor and expectations of high school. Residual benefits of implementing APHG at the freshman level also included the implementation of a mainstream Human Geography course that previously did not exist within the District. While there is room for further research as a result of the study, the study supported the implementation of APHG at the freshman level as an introductory course to the structure and rigor needed to be successful in Advanced Placement classes. iii Acknowledgements In the process of completing this research, I recognize that I could not have done it without the dedicated help of many people. I would like to thank the University of Oregon and the professors of the EDGE program for opening my eyes to the many ways geographic education is critical in today’s high schools. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Lynn Songer for her dedication and advising as I navigated my way through this process. There is no doubt that my ability to push my writing to the deadline caused stress in her as much as it caused stress in me. I would also like to thank Carol Biging and Barbara Hammond at Elk Grove High School. Their ability to gather information and organize it for me provided me with the basis for all of my research. They have been invaluable in my ability to complete this research successfully. I could not have completed this process if it was not for the generous support of my colleagues at Elk Grove High School. They readily provided suggestions and assisted in the dissemination of surveys. Specifically, I would like to thank Dan Davisson, teacher of AP World History, who provided invaluable suggestions and a sympathetic ear as I worked through the process. There is no doubt that this research would still be half finished if not for his support. Finally, I would like to thank my family. Whether it was stressing the importance of education when I was younger or encouraging me through the final stages of completing this research, they have always been my biggest supporters. I could not have completed this task if not for their unwavering support and belief in my abilities. iv Table of Contents Abstract...................................................................................................................... Acknowledgements ii ...................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review ....................................................................................... Chapter 3: Research Methods ................................................................................. Chapter 4: Results ...................................................................................................... 6 15 18 Chapter 5: Discussion ............................................................................................. 22 Appendix A: Data-Analysis .................................................................................... 29 ......................................................................................... 36 Appendix B: Data-Graphs Appendix C: Student Questionnaires .......................................................................... 37 Appendix D: Student Questionnaires: Selected Comments Bibliography ....................................... ........................................................................................................... 42 45 v Chapter 1 Introduction The front page in the May 31, 2011 edition of the Chicago Tribune greeted readers with the headline “Advanced Placement Class Opportunities Unequal.” The article outlines the inequities of Advanced Placement (“AP”) class availability across the State of Illinois despite noting that Advanced Placement classes have “long [been] considered the gold standard for college readiness.” With the inequities that are apparent within the system, the article challenges schools and school districts to provide greater opportunities for AP courses for all students but especially among the traditionally disenfranchised (minorities, impoverished and girls). While wealthier districts have had tremendous advantages in the implementation of AP courses, poorer districts have seen the gulf between them and their rich brethren widen. Within this context, and with the backdrop of AP courses offered to freshmen in Township High School District #214 (“District #214”) being challenged among some parents, it is imperative to investigate the viability, effectiveness and benefits of taking Advanced Placement Human Geography (“APHG”) at the freshman level. The aim of the project is to explore the relationship between APHG in the 9th grade and Advanced Placement World History in the 10th grade by comparing student test scores, attitudes and beliefs regarding the AP experience. District #214 is situated in the northwest suburbs of Chicago, Illinois and services the communities of Arlington Heights, Buffalo Grove, Elk Grove, Mt. Prospect, Prospect Heights, Rolling Meadows, Wheeling and Des Plaines. As the second largest district in the state of Illinois, its student population numbers 12,353 as of the 2009-10 school year (Township High School District #214 2011). The school district is recognized as a Blue Ribbon School District and has recently received the 2010 Lincoln Bronze Award for "Commitment to Excellence" that 1 recognizes the District for being a leader in “contributing to the economic development and ethical competitiveness in the state” (Friends of District #214 2011). The district is relatively affluent as the per capita income is $28,330 while the median income is $66,687 (Teacher Salary Info 2011). The location, prestige and affluence of District #214 has made it a centerpiece for reform and monitoring in the State of Illinois. Since the District has a large student body and considerable money to support them, it has faced tremendous scrutiny. The Lincoln Bronze Award is affirmation that the District has attempted to streamline its processes to make sure that it is fiscally responsible and an asset to its constituency. In this manner, the District, spearheaded by Superintendent David Schuler, developed three goals in 2007 that would be the crux of its guiding principles. One goal deals with increasing standardized test scores between a student’s 8th grade EXPLORE score and their Junior year ACT score; a second goal involves increasing the number of A’s, B’s and C’s in the District until a 95% success rate is attained in all classes; and a third goal states, “The number of students enrolled in at least one AP course will increase over the previous year, as will the number of students taking at least one AP exam and the number of students earning a passing score on an AP exam, until at least 50% of all students have earned a score of three or higher on an AP final.” The third goal became the basis for implementing new AP programs in all member schools including APHG during the freshman year. The APHG course supplanted a broader social science survey course called Honors Social Science. Some schools had implemented or experimented with APHG prior to the 2007 goals, but as a result of the new district goals, all schools needed to implement the APHG curriculum by the 2008-2009 school year. Elk Grove High School had never been involved with APHG prior to 2008-2009 and I was chosen, along 2 with Lindsay Gallagher, to spearhead the design, implementation and instruction of the course at Elk Grove High School. As reported by the Illinois State Report Card, Elk Grove High School is a predominantly white school with a large Hispanic population (Figure 1). About 22% of the school is defined as “low-income” and the population remains relatively transient in comparison with the state average (Figure 1). While the school has remained above the state average on the Prairie State Achievement Exam (“PSAE”) tests scores in math, reading and science, it falls far short of the 100% threshold declared by No Child Left Behind (NCLB). About 68% of students are meeting or exceeding standards in reading while 64.9% are meeting or exceeding standards in mathematics and 67% are meeting or exceeding standards in science (Figure 2). At this point, Elk Grove High School is currently not meeting Adequately Yearly Progress (AYP). In terms of AP participation, Elk Grove students took 993 AP tests in 2010 with 56.5% of the students achieving a score of 3 or above. All AP tests are scored on a scale of 1-5 with a “5” being the highest score and a “1” being the lowest score. According to the College Board website, a score of “3” or above is considered “qualified to receive college credit or advanced placement.” While AP participation ranked fourth among the six member schools in District #214, the “success rate” at Elk Grove High School of achieving 3 or above ranked last by 16 percentage points (Township High School District #214 2011). AP participation has steadily risen at Elk Grove High School in order to meet the district’s third goal and APHG was developed in order to enhance AP opportunities at the school. Elk Grove High School is fully vested in enhancing the number of AP classes offered, the number of students taking the AP test and the number of students achieving a 3 or above on the AP test. 3 The question regarding AP offerings, and the focus of this research, has centered on the implementation of a college-level course for high school freshmen. At a recent Open House, I fielded numerous questions ranging from the impact of a low grade on a student’s transcript to the ability to teach an authentic college-level class to 14 and 15-year-old students. These questions are a microcosm of the critique that APHG faces as it finds itself implemented at its largest numbers at the freshman level of high school. According to the 2010 Report on the Status of U.S. Geography Education, almost 51,000 students took the AP Human Geography test in 2009 with nearly 50% of all test-takers being in the 9th grade (Roth 2011). A rise in available AP tests throughout the four-year high school period has created a logjam of AP tests for upperclassmen while leaving the freshman year relatively devoid of AP content. AP Human Geography, in order to maintain its relevancy, has to establish itself as a bridge AP program from middle school to high school that generates a class rooted in rigor, that is accepting of a transitional status for students, that calms the fears of parents and establishes high standards of excellence as measured by the AP College Board. Placing APHG as a freshman level course not only enhances geographic awareness, but also establishes the tools and methods that are critical to be successful in other AP social science courses (World History, U.S. History, etc.). Content that is both implicit and explicit transfers to other courses, as well as expectations for the successful completion of any AP course (study skills, time management, test preparation, quality, course structure, critical thinking). Along this line, there is a need to prove that APHG, taken in the 9th grade, creates benefits for the student who then takes AP World History in the 10th grade. The benefits gained are evidenced in AP scores by the same students who take both tests and students who do not take APHG and through attitudes and beliefs generated through student surveys and discussions with school 4 administrators. Further benefits of the APHG curriculum is the establishment of a regular level Human Geography course that coincides with many of the themes of the AP course while also producing greater movement from the regular to AP sequence from the freshman to sophomore year. Figure 1 (Illinois Report Card 2010) Figure 2 (Illinois Report Card 2010) 5 Chapter 2 Literature Review The AP program, under the guidance of the College Board, has long operated as the conduit between high stakes high school curriculum and college preparation. Started under a pilot program in 1952 before being acquired by the College Board in 1955, the program was born out of a desire to universalize a public education program that lacked focus and direction. The stated mission of the College Board is, “to ensure that every student has the opportunity to prepare for, enroll in and graduate from college.” While the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) was the entry point for the College Board into public high schools, the Board recognized that expanding into the classroom and overseeing the way material was taught was critical for college preparation. In this manner, the Board has focused its work in three areas: College Readiness, College Connection and Success, and Advocacy. All three categories seek to prepare students for college, engage students in the process, and provide equitability for all students. As of today, the College Board administers a significant number of tests through its AP program. According to the 7th Annual Report AP Report (2011) produced by the College Board, the class of 2010 saw 3,018,460 students walk through the doors of their local high school. Of those students, 28.3% - or just over 850,000 - took an AP test while 16.9% of the class - just over 510,000 students - received a passing score of “3” or above. The trend has seen a nearly 100% increase in overall AP participation since 2001 while experiencing only a 5% drop in AP success scores as defined by receiving a “3” or above on the exam on a scale of 1 to 5 (College Board 2011). Considering that an additional 400,000 students are now taking the test, the slight drop in success could be predicted and seems less significant when compared with greater accessibility. Furthermore, the mere participation in an AP class garners tremendous benefits. According to 6 the 7th Annual AP Report to the Nation, A recent College Board study showed that students who scored 3 or higher on four popular AP Exams earned higher first-year GPAs, were more likely to continue on to a second year of college, and were more likely to attend selective institutions, on average, than students with comparable SAT scores and high school GPAs who did not take AP. (College Board 2011) The advantages of AP participation have long been claimed to be far-reaching and a predictor for post-high school success. In order to enhance the robust offerings of AP classes, the College Board introduced AP Human Geography (APHG) in the 2000-2001 school year. Despite having over 30 courses, APHG was offered as an additional social science class to enhance the way students view the complexities of physical and human environments on Earth. By using spatial concepts and analysis techniques, students gain a better understanding of the world in which they live and how the Earth’s processes combined with human interactions shape the world. With this backdrop, APHG has seen its test-taking participation increase from 3,272 students in 2001 to nearly 60,000 students in 2010 (Roth 2010). The majority of the increase in student participation in APHG has occurred in the 9th grade. Currently, nearly 50% of all students taking the test are in the 9th grade. However, the overall mean score for APHG is 2.56 and ranks last among all AP courses offered (Roth 2010). Considering the comparably low AP test scores among APHG students and the increase in student participation among a population that is four years away from college, the question becomes whether the subject and AP designation are appropriately placed and marketed. In order to establish a line of research, a consideration of benefits and hindrances of the AP program in general, and APHG at the freshman level in particular, must be examined. 7 The difficulty that has long plagued geographic education at the high school level is establishing a need and direction for the discipline within the high school curriculum. Cutter, Colledge, and Graf (2002) argue that geographers at the university level often focus their energy on small and focused problems that can be solved rather quickly while promoting their own ambitions toward tenure and monetary gain. Furthermore, the disconnect that university geographers have with other geographers and high school teachers becomes more pronounced when the discipline of geography has failed to identify the “big questions” that could guide geographic research and instruction (Table 1). To this degree, geography has found itself often Table 1 Big Questions in Geography 1. What makes places and landscapes different from one another, and why is this important? 2. Is there a deeply held human need to organize space by creating borders, boundaries, and districts? 3. How do we delineate space? 4. Why do people, resources, and ideas move? 5. How has the earth been transformed by human action? 6. What role will virtual systems play in learning about the world? 7. How do we measure the unmeasurable? 8. What role has geographical skill played in the evolution of human civilization, and what role can it play in predicting the future? 9. How and why do sustainability and vulnerability change from place to place and over time? 10. What is the nature of spatial thinking, reasoning, and abilities? (Cutter, Colledge and Graf 2002) operating outside of the core of American public education. As Murphy (2006) argues, “Geography instruction does not figure prominently in the curriculum of many primary and secondary schools, the discipline is absent from a number of influential colleges and universities, and it often struggles for resources and attention even at institutions that have formal geography programs.” The fact that geography has become marginalized in the curriculum, without a clear direction of how or why it needs to go forward, presents a difficult situation for the high school teacher looking to legitimize its existence in the ever-increasing high-stakes testing and cost-cutting environment of public education. Providing a direction for geographic education has come in a variety of forms. The U.S. Department of Education, in conjunction with business leaders, professionals, researchers, 8 professors and teachers, developed a report in 2009 that challenges geography educators to move beyond place-name identification to critical, skill-oriented geography concepts in order to bring the discipline into the mainstream (National Assessment Governing Board 2009). Murphy (2006) also argues that geography must move away from place-name identification and instead embrace a regional approach to geography that looks to understand the world in which we live, how that world came to be, and how that world can move forward. The leadership of the geography discipline recognizes that in order for the discipline to move into a greater level of relevancy it must move away from traditional assumptions of geography as a study shrouded in rote memorization and regurgitation. While traditional geographic outlooks over the past 50 years have been relatively narrow and disconnected from the world-at-large, geography is at an important defining moment in its history. Without a high-stakes, standardized test at the conclusion of its discipline and without a universalizing direction from professionals and academia, geography risks being replaced by other social science disciplines that have made investments in the structures of gaining a foothold in the American educational system (Cooledge 2002). Without a clearly defined direction, geographic education can look to its successes for inspiration. The development and implementation of APHG during the 2000-2001 school year helped give the discipline a much-needed high-stakes test to drive its decision-making at the high school level. The premise for devising a Human Geography class at the high school level was born, in part, out of studies regarding the lack of geographic awareness among high school students. Hess (2009) points to a recent survey of 17-year-old Americans that produced such startling statistics as “nearly a quarter of those surveyed could not identify Adolf Hitler; 10 percent think he was a munitions manufacturer,” or “more than a quarter think Columbus sailed 9 after 1750,” and more than half do not know about the Renaissance (Hess 2009). The lack of geographic knowledge and historical understanding among American students is concerning when considering the enhanced American role in global issues and a world that has become more and more globalized. Further identifying the lack of geographic awareness, Vanneman (1996) observed that rote knowledge was not the only deficient element among American students. The conclusions from the author identified deficiencies in core geographic concepts: space and place, environment and society, and spatial dynamics and connections (Vannemann 1996). The overarching problem facing the American student, therefore, is the inability to master a geographic skill-set that is rooted in educational theory and applicability to the real world. The need to coordinate and streamline geographic education is paramount to the continued relevancy of the discipline. Advanced Placement Human Geography, designed by critical university professors and chairs such as Alexander Murphy, Patricia Gober, David Lanegran, and Sarah Bednarz was developed with the goal of enhancing geographic awareness and accountability in the United States. To that end, Patricia Gober, former chair of the AP Human Geography Development Committee, stated, Given the importance of the AP Human Geography program to the discipline of geography, you will be doing an important service to the profession in recognizing the achievement of the AP Human Geography students and helping them integrate into the discipline of geography at the postsecondary level. AP Human Geography students come to our universities more interested in and better prepared to study geography. If only a small portion of test-takers become new geography majors, our discipline will grow and solidify its position as a core discipline in American higher education. (College Board 2006) The belief is that APHG is a gateway to further the relevancy of the discipline, enhance geographic awareness among students and promote future geographers in the field. With this 10 backdrop, it is imperative to understand the role of AP programs in the promotion of geography in America’s schools. Broadly speaking, the AP program has increased the rigor of the high school classroom while producing predicted results for future academic success. While examining the infancy of APHG, Bailey (2003) noted the potential (and in many cases realized) of the curriculum. The potential for APHG included, among others: Record numbers of university entrants with a systematic knowledge of the content and perspectives of introductory human geography; high levels of quality assurance, fairness and reliability in assessment; learning objectives that are both conceptual and content-driven; and seamless cooperation between school and university educators in course design, monitoring and development (Bailey 2003). The drive for AP programs in school districts across America allows for the legitimate and desired placement of APHG. As schools look to coordinate and streamline curriculums, it becomes intuitive that a mainstream version of Human Geography, targeted at the general ageappropriate population, becomes a byproduct of the AP program. Using APHG as a catalyst, geographic education has a pathway to become a core subject in schools across the nation. Recognizing the power of AP programs in steering curriculum decisions is only part of the issue facing educators; examining the positive impact of AP courses is another important aspect. As administrators face greater scrutiny in local papers, and as pressure remains on fiscal responsibility, decisions regarding wholesale changes in courses come under great consternation and reflection. Implementing curricula changes that embrace AP programs is filled with tremendous benefits that are often used to justify the high monetary costs being offset by the high educational enrichment. The research supporting the inclusion and predicted success of AP participants is tremendous. Realized gains occur at both the high school and collegiate level. At the high school level, students experience a program that is rooted in rigor and results-driven assessment. 11 In APHG, the normally semester-long college course can be stretched over an entire academic year thus allowing teachers to focus on such skills as critical thinking, geospatial concepts and enhanced writing techniques (Trite, Lange and Lange 2000). Furthermore, in order to reward these high achieving students that are taking on additional rigor, many schools offer GPA incentives that reflect the difficulty of the workload. In districts such as District #214, students receive an additional point toward their GPA for taking an AP course. Thus, on a fivepoint scale, an “A” in an AP class would receive a score of six, a “B” a score of five, etc. In addition, students often receive the benefit of greater access to high quality teachers and resources that is often limited to the rest of the school population (Santoli 2003). The cumulative effect of all of these benefits is greater accessibility to demanding universities and greater opportunities for success at the university-level. The impact of AP courses on university performance has been monitored since the creation of the AP program. Numerous studies have found a correlation between AP success and college success. One study “shows that students who take AP courses and earn AP grades of 3 or higher are more likely to graduate from college than students who take the course but do not take the exam, who in turn are more likely to graduate than students who do not participate in an AP course at all” (Dougherty, Mellor, and Jian, 2006 as cited by Handwerk, Tognatta, Coley and Gitomer, 2008). Identifying success on an AP exam by achieving a score of “3” or above, or simply partaking in the AP experience, achieves a corresponding success at the collegiate level. Additionally, students tend to take coursework and apply for college majors in subjects where high-level results were achieved on the corresponding AP examination (Morgan and Maneckshana 2000). As studies have supported the increased likelihood of graduation and course selection, so too do studies point to a greater sense of preparedness and slightly higher 12 GPAs in college (Santoli 2003). The benefits of AP courses are evident at both the high school and university level. Considering that some universities give college credit for receiving scores of “3” or above on AP tests, and the numerous other advantages substantiated by research, AP programs make a viable and critical argument to be placed in high schools across the United States. While researchers make a compelling case for AP programs, the program does not come without its critics. Some researchers argue that participation in AP programs alone do not account for long-term success or immediate success at the university level. Klopfenstein (2005) argues that the high school’s curriculum, family and school characteristics are the most critical factors in determining college success. Despite numerous journals and articles attempting to draw a statistical connection with AP participation and collegiate success, Klopfenstein argues that none are able to draw the connection. Burney (2010) goes on to argue that minority status, individuals receiving free and reduced lunch, and community educational levels are the primary determination of academic success, not AP participation. In turn, the inability of programs such as APHG to have a universalized program is a detriment to consistent and viable curriculum prior to entering college. Since these programs lack consistency, and the acknowledgement of “success” rests on the results of one test over a four hour time period, AP programs have a clear gap in justifying their absolute existence at the high school level with valid and reliable assessment practices. While recognizing the flaws and limitations of the AP program is critical for objective inquiry, clearly the benefits of the program make it worth investigating further. The unclear direction of geographic education in American schools as a core subject is addressed, in part, by the overarching themes inherent in the guidance provided by the APHG curriculum. Simply 13 relegating Human Geography to an essential class because of the mere existence of an AP course is naïve and misdirected; however, examining the quantifiable and qualitative benefits of APHG in a high school district could provide greater merit to expanding the course’s placement in the social studies department. Furthermore, when considering that nearly half of all current APHG students are freshmen in high school, it is critical to examine the direct and indirect benefits of placing the course at the freshmen level in the sequencing of courses within the social science curriculum. Test data within a school, across the District, between freshman and sophomore year social science courses, among heterogeneous populations (male/female, white/Hispanic) and student surveys will be analyzed to assess the importance of APHG in general and APHG as a freshman-level course in particular. Considering all of the data, and in light of current research, an inquiry should reveal the need for APHG as a driving force in steering geographic education in American schools. 14 Chapter 3 Research Methods The experiment was developed to compare the impact of participating in a freshman-level APHG course and taking the APHG examination with a focus on the results in the following areas: overall APHG performance, differences in male and female performance, differences in white/Hispanic and white/non-Hispanic performance, and the impact on student results during a student’s sophomore year performance on the AP World History examination. The compilation and examination of the data set out to see if APHG was appropriately placed at the freshman level and the residual impact in other AP classes by implementing the APHG curriculum. After acquiring the data, a variety of tests and statistical analyses needed to be performed to either prove or disprove the hypothesis set forth in this research. In order to establish a means of assessing the benefits of APHG, quantitative data and qualitative data had to be gathered from District #214. Steve Cordogan, Director of Research and Evaluation for the District, and Carol Biging, Assessment Coordinator for Elk Grove High School, operated as the primary sources of disseminating raw data. The data provided by Mr. Cordogan and Mrs. Biging came from compiled data provided by the College Board. The data came from the College Board in paper and electronic formats. Mr. Cordogan and Mrs. Biging compiled, arranged and merged the information into an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis. The data was provided for further analysis at the beginning of June 2011. The raw data that was provided by Mr. Cordogan and Mrs. Biging was disaggregated by school and identification number. The information also included gender, ethnicity, EXPLORE reading score, AP Human Geography test year, AP Human Geography test score, AP World History test year, and AP World History test score. The EXPLORE reading score is particularly 15 noteworthy because District #214 uses EXPLORE reading scores as a primary criteria for admittance into APHG. Students take a statewide EXPLORE test during 8th grade and the results determine placement in subjects such as math, english, science and social studies. Since District #214 uses tracking for students, the scores, combined to a lesser degree with teacher recommendations, middle school grades and parental preference determine high school placement levels in Honors/AP, mainstream or skills. The AP World History scores will then be used in conjunction with APHG exam. In order to make the data comparable, several formulas and tests needed to be generated and monitored. First, the information was sorted by school and year in which the APHG test was taken. The total number of tests, the total number of students receiving scores of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, the overall “success rate” scoring “3” or above for APHG and AP World History were established. Further analysis was done on the performance of males/females and white, Hispanic/white, non-Hispanic students. After establishing these comparable numbers, formulas were generated to calculate the number of same students who increased/remained the same/decreased between APHG and AP World History. This in turn generated the composite score of students taking AP World History who had and had not taken APHG prior to taking AP World History. Furthermore, a test was performed to differentiate students’ performance on the AP World History examination in “like” EXPLORE ranges (under 12, 13-15, 16-19, 20-23, over 24) whether they had or had not taken APHG prior to taking AP World History. Considering the District’s emphasis on EXPLORE scores as a primary basis for placement, singling-out this criteria was critical for comparison in year-over-year benefits of taking the APHG examination. In order to assess the statistical significance of any of the aforementioned data, an f-test and a ttest were performed through Excel. The final Excel information can be seen in Appendix A. 16 The qualitative research was generated through a survey administered to Elk Grove High School students following the completion of AP testing in early May 2011. The APHG survey (Appendix C) was given on May 23, 2011 to all students enrolled in APHG at Elk Grove High School regardless of their participation in the AP examination. The AP World History survey (Appendix C) was given at the same time to students enrolled in AP World History at Elk Grove High School regardless of their participation in APHG or their participation on the AP World History examination. The teachers were administering the surveys were instructed to give very little explanation regarding the survey in the hopes that students would not be swayed in their opinions. Students had the option of providing their name or remaining anonymous. The results of the qualitative survey will be further outlined in the next chapter and in Appendix D. 17 Chapter 4 Results Quantitative Research The data show that in years in which APHG was offered to students, subsequent years saw a corresponding increase in the number of AP World History tests taken (Table 2). Table 2 further shows that four of the six schools in the district have seen growth in the number of APHG test takers while two schools, Wheeling and Rolling Meadows (not referenced in Table 2), have not yet introduced the course to their student population. Data for examinations in APHG and AP World History were used to compare the impact of participation in APHG on the subsequent results in AP World History. For all schools and the District total, every year of acquired data was used to compare the results of students who had taken both APHG and AP World History with students who had only taken the AP World History examination. Furthermore, a comparison was used for the performance on the AP World History examination for students in the same EXPLORE reading band who had taken APHG and students who had not taken APHG. In order to clarify the correlation, an f-test was performed to establish the level of variance for each year being examined. The results of every f-test necessitated further inquiry using a homoscedastic t-test with two tails. While a variety of results were achieved, most operated within a standard that allowed for comparable data within the data set. When comparing the performance of males and females in District #214 in APHG, males have achieved a higher “success” rate than their female counterparts (Appendix A). When comparing male and female performance between APHG their freshman year and AP World History their sophomore year, the gap across the district nearly doubles. Within individual 18 schools, out of 14 possible years worth of comparisons, females achieved a higher success rate than their male counterparts two times in APHG. Within individual schools, out of 30 possible years worth of comparisons, females achieved a higher success rate than their male counterparts three times in AP World History. The performance of white/non-Hispanic students has surpassed the performance of white/Hispanic students in District #214 (Appendix A). When comparing white/non-Hispanic and white/Hispanic performance between APHG their freshman year and AP World History their sophomore year, the gap across the district nearly triples. Within individual schools, out of eight possible years worth of comparisons, white/Hispanic students achieved a higher success rate than their white/non-Hispanic counterparts two times in APHG. Within individual schools, out of 28 possible years worth of comparisons, white/Hispanic students achieved a higher success rate than their white/non-Hispanic counterparts eight times in AP World History. Table 2-AP Test Participation in Applicable District #214 Schools ’04-‘05 Buffalo Grove Elk Grove Hersey Prospect Human Geography World History Human Geography World History Human Geography World History Human Geography World History ’05-‘06 ’06-‘07 4 ’07-‘08 49 ’08-‘09 41 ’09-‘10 104 54 73 80 130 88 103 39 46 43 86 64 118 113 107 93 104 172 156 10 4 43 146 81 81 131 128 19 Qualitative Research Students in APHG and AP World History at Elk Grove High School were administered a survey on May 21, 2011. The surveys can be found in Appendix C. Students were asked questions that were both qualitative and quantitative in nature. The quantitative data for APHG students focused on: 1) Preparedness for the multiple-choice portion of the exam, 2) Preparedness for the free response portion of the exam, 3) Quality of the review sessions, 4) Quality of the instruction during the year, 5) Transition from middle school to college-level work, and 6) Performance on the APHG exam. The results of the quantitative part of the survey can be found in Table 3. The qualitative results from the APHG survey asked students questions regarding their experiences in the class. Individual comments can be found in the Discussion section of this paper and in Appendix D. Students in AP World History were asked questions that were both quantitative and qualitative in nature. The quantitative data for AP World History students focused on: 1) Preparedness before taking the APHG exam the previous year, 2) Preparedness before taking the AP World History exam this year, 3) Score on the APHG test, and 4) Predicted score on the AP World History test. The results of the quantitative part of the survey can be found in Table 4. The qualitative from the AP World History survey asked students questions regarding their experiences in the class. Individual comments can be found in the Discussion section of this paper and in Appendix D. 20 Table 3-AP Human Geography Survey Results at Elk Grove High School-2011 Survey Question Preparedness for the multiple-choice portion of the exam? Preparedness for the free response portion of the exam? Quality of the review sessions? Quality of the instruction during the year? Transition from middle school to college-level work? Score 7.04/10 6.80/10 6.87/10 8.09/10 6.43/10 Table 4-AP World History Survey Results at Elk Grove High School-2011 Survey Question How prepared did you feel before taking the AP Human Geography test last year? How prepared did you feel before taking the AP World History test this year? What score did you achieve on the AP Human Geography exam? What score do you predict you will receive on the AP World exam? Score 5.64/10 7.08/10 2.60/5 3.34/5 21 Chapter 5 Discussion The results of the data gathered demonstrate generally positive benefits regarding a student’s participation in APHG at Elk Grove High School specifically and in the District in general. When examining the quantitative data regarding APHG participation, students see a general increase in their own performance year-over-year and students within the same EXPLORE reading range see higher results in AP World History if they have taken APHG than their counterparts who did not take APHG. Across the district, nearly 78% of students receive the same or a higher grade if they take both AP tests (Appendix A). When considering mean scores, students who take both AP tests, achieve an AP score on their World History test that is nearly .5 points higher. This jump amounts to a nearly 10% increase in their overall score. While other variables could clearly contribute to the performance of any one student on any one day (socioeconomic status, parental educational attainment, nutrition, etc.), t-test results point to a positive correlation between participation in APHG and student performance during their sophomore year on their AP World History examination. The placement of APHG at the freshman level has created controversy in District #214 among teachers and parents who question the validity of providing a college course to freshmen in high school. When examining the data for the District in general, and most schools in most years specifically, students have consistently outperformed the national averages in APHG (Roth 2010). Placing the APHG course during a student’s freshman year does not inhibit their performance when compared with national results and leads to additional benefits as outlined in this research. Further research would need to be conducted to differentiate the results of students at each grade level to see the differences in mean scores and “success rate” of scoring a “3” or 22 higher. An intuitive conclusion would be that students perform better during their senior year because of a variety of factors such as maturity, previous AP participation, more developed study skills, etc. However, considering the additional benefits outlined in this research, a serious study would need to be performed to determine the benefits and hindrances of the placement of APHG. The District’s desire to use EXPLORE reading scores as a primary determination in a student’s participation in APHG during their freshman year is of critical importance when comparing data results about the rationale for placing the course first in the social science sequence. The relative bump in student performance during their sophomore year could be random if identified in any one year; however, consistently improved performance across years and schools leads to the reasonable conclusion that APHG has an impact beyond the immediate instruction of the course. The results from the four schools in the District that had results in 2010 illustrate the higher scores received by students who did and did not take APHG (Appendix B). When used in conjunction with statistical analyses involving f-tests and t-tests, it is apparent that APHG has a positive impact on student achievement on the AP World History exam regardless of EXPLORE score. Additionally, when considering such comments from Elk Grove High School students as “AP Human Geography really prepared me for the rigor of AP World History,” and “I really learned time management skills. And I couldn’t do what I always did in junior high!” it is apparent that there is a change in the way students approach the process of performing in school (Appendix D). Advanced Placement Human Geography raises the expectations and redefines the notion of high-quality performance. While the use of EXPLORE reading scores is of critical importance for placement into APHG, the results garnered from taking the AP test need to be examined from a variety of angles. The District has seen males outperform their female counterparts on the AP test over the 23 last year by a mean score of 3.49 for males and a 3.36 for females (Appendix A). Additionally, white/non-Hispanic students outperform their white/Hispanic student counterparts by a score of 3.43 to 3.25 (Appendix A). When examining the scores at individual schools, the trend remains consistent. Qualitative data from student surveys does not shed any light as to the reason why male and white/non-Hispanic students perform at a higher level. Further examination of both female student performance and white/Hispanic student performance would be critical in explaining the reasons for their lower performances when compared with their peers. The qualitative research supports a shift in the efficacy experienced by students who participate in an AP class as an underclassmen. Sifting through the surveys resulted in some common themes among students. Students experienced an increase in rigor and subsequent expectation in the quality of work that needed to be produced (Appendix D). While students felt the transition was somewhat difficult (a 6.87/10 on the survey) from middle school to high school, there was an overwhelming feeling that the experience was positive (8.18/10) and will likely prepare them for the challenges that other AP classes offer (Table 3). The observation among freshmen APHG students was substantiated by AP World History students who saw an increase in their AP test scores and an acknowledgement that APHG assisted in their preparation from the beginning of the year. One student noted, “while AP Human Geography was not a perfect match for AP World History, it taught me all of the necessary skills to be successful starting from the beginning of the year. This no doubt helped in my performance.” Along this line, benefits for APHG and AP World History students included learning how to study, increasing vocabulary acquisition, acquiring time management skills, applying theoretical frameworks to the real world and managing the multiple-choice portion of the exam (Appendix D). Students identified numerous ways that APHG aided their educational pursuits which is 24 important for two reasons: 1) the items identified are critical for academic success and 2) the students recognize the value-added by taking APHG as a freshman despite the difficulty of the course coming immediately after middle school. As schools struggle to implement geographic education at the high school level, it is important to note that the existence of APHG in District #214 created a district-wide mandate that all schools must develop a general education and skills-level track that mimics the AP course. In turn, the District went from offering approximately 400 students across the District a geography course to the majority of its approximately 3,000 freshman students. As the District looked to fulfill its mandate outlined in its third goal geared toward AP participation and success, it looked to mirror its general education and skills-level classes with its AP counterparts; thus, the creation of Human Geography courses in the District, albeit taught thematically, was developed and implemented. The benefit for the District has been an increase in the number of students taking subsequent AP tests; the benefit for the student is, if consistent with these results, an increase in their own performance over subsequent social science AP tests. One component that remains unanswered is why students in higher EXPLORE reading bands opt out of participating in the examination or class for APHG. The research supports the statement that students who take APHG perform at a higher level than students who do not take APHG, regardless of their EXPLORE reading band. Theories abound on the topic: socioeconomic status, race, parental educational attainment, belief in competency, future goals, home pressures, etc. Further research in this realm could provide greater clarity on why students who have been identified as academically competent choose to not participate in APHG or in the APHG examination. Further inquiry could examine the role of teachers prior to and within the APHG course and their impact on student performance. 25 The limitations within this research are worth addressing. The data compiled from District #214 exists for the last five years. Schools such as Hersey and Buffalo Grove have research over those five years while schools such as Elk Grove and Prospect have only one year of data and Wheeling and Rolling Meadows have zero years of research. The lack of data overall and within any one year allow for small sample sizes that impact results and create anomalies. Along these lines, each school within the District experiences a different studentbody with different feeder schools and thus causes a difference in skill sets as students enter high school. Schools such as Rolling Meadows and Wheeling share similar characteristics in terms of socioeconomic status, race, parental degree attainment, etc. to Elk Grove, for instance, yet their lack of data causes difficulty in comparing “like” schools. Additional limitations to the research are the use of AP test scores as the sole source of analysis. Many factors can contribute to student test performance on any given day. While the course grade reflects student achievement over the course of several months, the three hour AP test reflects knowledge under time constraints and limited questioning. Students who experience test anxiety, eat an improper diet, are dealing with personal issues or experience inadequate sleep, etc. on the days leading up to the test or before the test can suffer results that do not accurately reflect their knowledge gained. Other factors such as travel history, parental educational attainment or poverty, to name a few, could adversely impact student performance in the course and/or on the AP test. Finally, when comparing APHG scores with AP World History scores, some students who performed worse on the APHG test have been removed from the sample thus restricting a truly “apples-to-apples” comparison. While looking at “like” students who saw their AP World History test score, increase, decrease or remain the same who also took 26 the APHG exam was an attempt to address this issue, it clearly fails to address the reasons why certain students drop out of the course or do not take the AP World History examination. In addition to the aforementioned areas where further research could be beneficial, there is additional areas where further research would be appropriate. The research currently examines the impact of APHG on AP World History. Expanding the research to include all social sciences may shed further light on the long-range impact of APHG. Also, examining the impact of poverty on results would be especially important for schools that experience higher rates of poverty. Using free and reduced lunch as a measurement for poverty, schools could use the information to identify areas of strength and areas of improvement. Since this research focused only on District #214 schools, further research could compare “like” schools across the country so that student bodies are more similar. Additionally, research could look at comparing scores of students at each level (freshman, sophomore, junior, senior) to see the impact of APHG as a freshman-level course. While limitations to the research are noteworthy, limitations as recognized by AP World History students may help to provide for additional avenues of inquiry. As recognized by the students, APHG provides help in a variety of ways but fails to address the writing needs experienced in the AP World History curriculum. The movement from Free Response Questions in APHG to stylized essay questions in AP World History is clearly problematic for students and a source of tremendous difference between the courses. Considering these differences, APHG does not seem to adequately prepare students for writing beyond the curriculum. Further examination of this writing piece could allow for higher student achievement in APHG and the structures necessary to have long-term writing growth as a result of taking the course. 27 The conclusions generated from this research are positive overall. District #214 has seen an increase in AP enrollment and AP test scores since it implemented APHG. Students feel more prepared to tackle the rigors of AP World History as a result of taking APHG. Students who read at the same level and have taken APHG perform at a higher level on their AP World History exam than their counterparts who did not take APHG. The evidence suggests that taking APHG as a freshman provides a skill-set, mind-set and experience that leads to long-term educational growth as measured by student achievement and attitude. 28 Appendix A Data-Analysis AP Human Geography and AP World History Data Based on AP Test Scores, Gender, Ethnicity and Same Student Comparisons 29 AP Human Geography and AP World History Data Based on AP Test Scores, Gender, Ethnicity and Same Student Comparisons 30 AP Human Geography and AP World History Data Based on AP Test Scores, Gender, Ethnicity and Same Student Comparisons 31 AP Human Geography and AP World History Data Based on AP Test Scores, Gender, Ethnicity and Same Student Comparisons 32 AP World History Test Performance Based On EXPLORE Reading Scores and AP Human Geography Participation 33 AP World History Test Performance Based On EXPLORE Reading Scores and AP Human Geography Participation 34 AP World History Test Performance Based On EXPLORE Reading Scores and AP Human Geography Participation 35 Appendix B Data-Graphs 36 Appendix C Student Questionnaires 37 APHG May 23, 2011 Post Exam evaluation Name (optional): Please answer the following questions truthfully and honestly, elaborating on details wherever possible. Don’t worry about hurting my feelings! Your responses to these questions will help me greatly in preparing future students for the APHG exam. Thank you! Please use a sheet of lined paper if you need additional space. On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being the worst and 10 being the best, how would you rate the following? 1. Preparedness for the multiple-choice portion of the exam? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2. Preparedness for the free response portion of the exam? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3. Quality of the review sessions? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4. Quality of the instruction during the year? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 5. Transition from middle school to college-level work? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Open-ended questions. 6. Based on the multiple-choice questions on this year’s APHG exam, do you feel that you were adequately prepared to be successful? Explain ways in which you were or were not prepared. 7. Based on the FRQ questions on this year’s APHG exam, do you feel that you were adequately prepared to be successful? Explain ways in which you were or were not prepared. 38 8. How do you feel about your out of class review for the exam? Are there anything suggestions you have with regard to how I approached this process with you? Are there suggestions you would give future APG students to be more successful? More time, less, etc…. 9. On a scale of 1-5, how do you feel you scored on this exam? 1 2 3 4 5 Did not take Briefly explain why you feel this way. 10. In retrospect, are you happy that that you decided to enroll in APHG? Briefly explain. 11. Looking ahead, do you feel like you are prepared for the challenges of future AP course at Elk Grove High School (such as AP World History)? Please explain ways in which you feel prepared/unprepared. 12. Looking forward, do you feel that being a student in APHG will make you a better college student as well as having a better understanding of how the world works? Please explain. 39 AP World History May 23, 2011 Post Exam evaluation Name (optional): Please answer the following questions truthfully and honestly, elaborating on details wherever possible. Don’t worry about hurting my feelings! Your responses to these questions will help me greatly in preparing future students for the transition between APHG and AP World History. Thank you! Please use a sheet of lined paper if you need additional space. On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being the worst and 10 being the best, how would you rate the following? 1. How prepared did you feel before taking the AP Human Geography test last year? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2. How prepared did you feel before taking the AP World History test this year? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4. What score did you achieve on the AP Human Geography exam? 1 2 3 4 5 Did not take 5. What score do you predict you will receive on the AP World exam? 1 2 3 4 5 Did not take 3. If the numbers are different, briefly explain what accounts for the difference. 6. When comparing the multiple-choice sections, how much did APHG help in terms of preparing you for the difficulty of the questions in AP World History? 7. When comparing the writing sections, how much did APHG help in terms of preparing you for the difficulty of the writing in AP World History? 40 8. In what areas did APHG help in preparing you for AP World History? 9. In what areas did APHG inadequately prepare you for AP World History? 10. Do you feel that taking an AP course as a freshman was beneficial in your academic performance in other areas at Elk Grove High School? Briefly explain the ways in which it helped. If you did not take AP Human Geography last year, please complete the questions below. 11. If you did not take APHG last year, how did regular Human Geography prepare you for AP World History? 12. If you did not take APHG last year, how did regular Human Geography not prepare you for AP World History? 41 Appendix D Student Questionnaires: Selected Comments AP Human Geography 10. In retrospect, are you happy that that you decided to enroll in APHG? Briefly explain. “Yes, it was a challenging, yet helpful experience. It has prepared me well for future AP classes.” “We got to explore topics more in depth. We move at a perfect pace, where some of my classes move too slow. People were serious about learning.” “I’ll be disappointed if I can’t use it as college credit but I got more than just knowledge out of this course.” “I think enrolling in this course was the best part of freshman year.” “I think the experience gave me an opportunity to see how real college classes would be like. Such as the pressure and work involved.” “Preparing for the exam helped my study skills.” “Yes because I now realize how little work some other classes require and how achieving more can be successful.” “It was more of a challenge (which I liked).” 11. Looking ahead, do you feel like you are prepared for the challenges of future AP course at Elk Grove High School (such as AP World History)? Please explain ways in which you feel prepared/unprepared. “Taking the APHG test has helped me understand what I should be studying and how to do it in the future.” “I know what to expect now, so I believe I’ll do just as well or better because I have had the exposure of an AP class.” “I think this class has prepared me for all the future work, reading and notes to come.” “I know how much more you have to put in to it and what’s expected.” “I feel like I am used to the workload and can be successful.” “The class showed me that I need to put in some extra effort to be successful.” “Yes because now I know what you have to do to be successful in AP (I know what to expect).” “I now see how much work I had to put in to get a good grade.” 42 12. Looking forward, do you feel that being a student in APHG will make you a better college student as well as having a better understanding of how the world works? Please explain. “Yes, because I know what is required & am used to the things we need to do.” “I know what to expect now that I have taken this class. I am more prepared now than last year for sure.” “This has helped me to budget my time a lot better.” “The material I learned in this class made me more aware of the culture and geography of the world.” “Yes because it prepared me for the difficulty and also the work load and work ethic.” “The amount of work & studying gave me a good perspective.” AP World History 6. When comparing the multiple-choice sections, how much did APHG help in terms of preparing you for the difficulty of the questions in AP World History? “APHG multiple choice was difficult; I would argue more difficult than AP World. The difficulty of APHG helped me to know how typical AP questions are asked and how to look for key words within the question.” “It helped with the narrowing down of the answers and crossing off wrong ones and stuff like that. It did also help with the realization of actually how specific the multiple choice questions really are.” “The test taking style was similar to the structure of both exams.” “It helped me understand that the questions aren’t just based on facts, they want to know if you know why everything happened.” “It helped me understand that I needed to use outside context for each question to relate it to the answers.” 8. In what areas did APHG help in preparing you for AP World History? The intensely difficult tests and rigorous course helped to se the stage for APWH. APHG gives you the foundation for APWH and ultimately all other AP classes as well.” “AP Human Geography really prepared me for the rigor of AP World History.” “It helped with seeing how much homework there would be, the expectations of you with your work and your expected responsibility level.” 43 “Vocab terms, test taking style, layout of countries and landforms and social ideologies.” “The workload from APHG was still applicable in World History, possibly even more.” “Covering the vast content.” 10. Do you feel that taking an AP course as a freshman was beneficial in your academic performance in other areas at Elk Grove High School? Briefly explain the ways in which it helped. “I really learned time management skills. And I couldn’t do what I always did in junior high!” “Yes, APHG gives you a taste of what other AP classes will be like. It is like a transitionary step that prepares you for the next level (APWH).” “I do believe the experience will definitely benefit me as a preparation for college” “Yes, I would say it has helped me in reading and writing due to being exposed to sophisticated ideas.” “It did give me an academic advantage because I was expecting the same level of classwork in all classes.” “Yes! The reading helped a lot! Analyzing text and drawing simple conclusions.” “Yes. Taking a rigorous course early on prepared me and helped prioritize my other classes.” 44 Bibliography 1. Bailey, A. “Recruiting and preparing students for university geography: Advanced Placement Human Geography.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 27, no. 1 (2003): 7-15. 2. Burney, V. “High achievement on Advanced Placement exams: The relationship of school-level contextual factors to performance.” Gifted Child Quarterly 54, no. 2, (2010): 116-126. 3. Cutter, S. L., Golledge, R. and Graf, W. L. “The Big Questions in Geography.” The Professional Geographer 54 (2002): 305–317. 4. Dougherty, C., Mellor, L., and Jian, S. “The Relationship Between Advanced Placement and College Graduation.” National Center for Educational Accountability (2006), www.nc4ea.org (Accessed May 30, 2011). 5. Friends of District 214. "Positive Accomplishments Of High School District 214." (2011). http://www.friendsofdistrict214.com/accomplishments.php (Accessed June 2, 2011) 6. Handwerk, P., Tognatta, N., Coley, R., Gitomer, D. “Access to Success: Patterns of Advanced Placement Participation in U.S. High Schools.” Educational Testing Service. (2008) http://www.ets.org (Accessed June 6, 2011). 7. Hess, F. “Still at risk: What students don't know, even now--a report from common core.” Arts Education Policy Review 110, no. 2 (2009): 5-20. 8. Illinois Interactive Report Card. “Elk Grove High School.” (2011) http://iirc.niu.edu/School.aspx?source=School_Profile&schoolID=050162140170002&le vel=S (Accessed July 21, 2011) 9. Illinois School Report Card. “Elk Grove High School.” (2010) http://www.d214.org/reportcards (Accessed June 12, 2011). 10. Klopfenstein, K. “The Advanced Placement Performance Advantage: Fact or Fiction.” American Economic Association (2005) http://www.aeaweb.org/assa/2005/0108_0302.pdf (Accessed January 10, 2011) 11. Klopfenstein, K. “Recommendations for Maintaining the Quality of Advanced Placement Programs.” American Secondary Education 32, no. 1 (2003): 39-48. 12. Mattern K. D., Shaw, E. J., and Xiong, X. “The Relationship Between AP Exam 45 Performance and College Outcomes,” The College Board. (2009) http://professional.collegeboard.com/profdownload/pdf//09b_269_RReport2009_Groups _Outcomes_WEB_091124.pdf (Accessed June 8, 2011) 13. Morgan, R., and Maneckshana, B. “AP students in college: An investigation of their course-taking patterns and college majors.” Princeton, N.J.: Educational Testing Service, 2000. 14. Murphy, A. B. “Enhancing Geography's Role in Public Debate.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96 (2006): 1–13. 15. National Assessment Governing Board. “Geography Framework for the 2010 National Assessment of Educational Progress.” U.S. Department of Education (2009) www.nagb.org/publications/frameworks/gframework2010.pdf (Accessed January 8, 2011). 16. Rado, D., and Malone, T. "AP unequal in Illinois, with thousands of students shut out." The Chicago Tribune. 30 May 2011. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2011-0530/news/ct-met-advanced-placement-0531-20110530_1_lisle-school-board-massaccounty-high-school-rigorous-classes. (Accessed June 2, 2011). 17. Roth, S. 2010 Report On the Status of U.S. Geography Education. (National Geographic Society: 2010). 18. Santoli, S. “Is there an Advanced Placement advantage?” American Secondary Education 30, no. 3 (Summer 2009). 19. Teacher Salary Info. "Township High School District 214 Average Teacher Salary & How to Become a Teacher." (2011) http://www.teachersalaryinfo.com/illinois/teacher-salaryin-township-high-school-district-214/ (Accessed June 2, 2011). 20. The College Board. "AP: The Score-Setting Process." College Admissions - SAT University & College. http://www.collegeboard.com/student/testing/ap/exgrd_set.html (Accessed June 8, 2011). 21. Township High School District 214. "Facts and Statistics." http://www.d214.org/district_information/facts_and_statistics.aspx. (Accessed January 10, 2011). 22. Trites, J., Lange, J. and Lange, D. “Challenges of Teaching Advanced Placement Human Geography.” Journal of Geography 99, no. 3 & 4 (May 2000): 169-172. 23. Vanneman, A. Geography: What Do Students Know, and What Can They Do? National Assessment of Educational Progress. (December 1996). http://nces.ed.gov/pubs97/web/97579.asp (Accessed June 2, 2011). 46