Colonial Legacies and Territorial Claims Paul R. Hensel Department

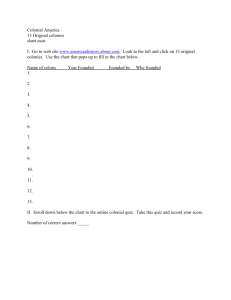

advertisement