The effects of residential locality on parental and alloparental

advertisement

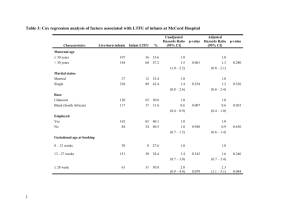

The Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and Alloparental Investment among the Aka Foragers of the Central African Republic Courtney L. Meehan Washington State University In this paper I examine the intracultural variability of parental and alloparental caregiving among the Aka foragers of the Central African Republic. It has been suggested that maternal kin offer higher frequencies of allocare than paternal kin and that maternal investment in infants will decrease when alloparental assistance is provided. Behavioral observations were conducted on 15 eight- to twelve-monthold infants. The practice of brideservice and the flexibility of Aka residence patterns offered a means to test the effect of maternal residence on parental and alloparental investment. There was significant variation in the frequency of investment and who supplied care to infants depending on whether mothers resided with their kin or their husbands' kin. However, in spite of the variation in allocare, when all categories of caregivers were examined collectively, infants received similar overall levels of care. KEY WORDS:Aka foragers; Alloparenting; Hunter-Gatherers; Infant care; Parental investment ver the past several years there have been considerable and exciting additions to the theories of infant and child development. Although research has traditionally focused on the mother as the central component of successful infant development and secure attachments (Bowlby 1969), recent work particularly among forager groups (Blurton Jones 1993; Hewlett 1989; Ivey 1993, 2000; Tronick, Morelli, and Winn 1987) has led to a reexamination of this O Received March 2, 2004; accepted June 4, 2004; final version received August 2, 2004. Address all correspondence to Courtney L. Meehan, Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-4910. E-mail: meehan@mail.wsu.edu Human Nature, Spring 2005, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 5 8 - 8 0 . 1045-6767/98/$6.00 = .15 Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and AUoparental Investment 59 tenet and has given credence to the possibility that alloparenting is underrepresented in our attempts to understand infant care (Hrdy 2005). Alloparents are individuals other than the biological parents who invest in children. They have been shown to increase maternal reproductive success (Bereczkei and Dunbar 2002; Sear et al. 2003) and aid in infant survivorship (Hawkes et al. 1997; Ivey 2000). Studies have shown that humans are cooperative childrearers and that successful rearing of offspring may be dependent on alloparental assistance (Hrdy 2005; Ivey 2000). In light of the extensive nature of food sharing, not to mention basic childcare offered by alloparents to infants, humans are considered cooperative breeders. As Hrdy (2005) notes, the unifying characteristic of cooperative breeding systems is that alloparental assistance is essential for the successful rearing of offspring. Among cooperative breeding species, alloparents should alter the tradeoff between quality and quantity through their assistance. Maternal reproductive success should be increased through the supplemental assistance of alloparents, even when mothers reduce interbirth intervals or their overall level of investment (Hrdy 1999, 2005). Among non-human species, alloparents allow mothers to breed again sooner without risking the survival of their current offspring (Emlen 1992a, 1992b; Solomon and French 1997; Stacey and Koenig 1990). Maternal cost/benefit tradeoffs between future and current reproduction and quality versus quantity of offspring are thereby offset and the costs lowered by alloparental assistance. Both mothers and alloparents should select particular investment strategies that increase their fitness. The costs and benefits of particular behavioral strategies are considered against the background of the social and physical environment and alternative strategies (Williams 1966). Alloparents in many species behave in a way that results in these maternal benefits, but Hrdy (2005) notes that lengthy human lifespans have made it difficult for many researchers to examine the overall impact that alloparents have on maternal reproductive success. However, several studies among humans illustrate that alloparents can lower maternal costs and increase maternal reproductive success (Flinn 1989; Kramer 2002; Sear et al. 2003; Turke 1988). Although the benefits of alloparental assistance on maternal fitness are clear, Ivey (2000) notes that among the Efe the motivations for alloparents to cooperate in childrearing systems are often difficult to tease apart. Several hypotheses, stemming from a life history perspective, have been tested among populations as a means of examining the socioecological conditions that may foster alloparental caregiving. First, alloparents gain inclusive fitness benefits from investing in infants. The most common form of alloparenting is from genetically related individuals (Hrdy 1976, 1999; Ivey 1993, 2000; Weisner and Gallimore 1977). The higher the degree of shared genetic relatedness, the more investment one would predict. Nepotistic alloparental investment can increase the caregivers' fitness through the survivorship and success of related 60 Human Nature / Spring 2005 infants. Second, reciprocity has been hypothesized as a means by which alloparents may receive immediate or delayed benefits for their contributions. Alloparents can receive reciprocal investment in their own children or a variety of other benefits that may enhance their fitness (Elmen 1994; Ivey 2000; Strassman and Clarke 1998). For example, Elmen (1982a, 1982b) noted that unrelated helpers benefit from aiding the reproductive success of another if the environment is marginal and resources for reproduction are unpredictable. HYPOTHESES This study examines parental and alloparental caregiving among the Aka foragers in light of the cooperative breeding hypothesis. The following hypotheses address the socioecological conditions that affect maternal and alloparental investment strategies. Variation in residence patterns is used to examine intracultural variability in caregiving practices. Hypothesis la. Significant differences exist in the type (high- and lowinvestment care) and frequency of allocare offered depending on whether families reside matrilocally or patrilocally. Alloparents will offer higher frequencies of assistance when the potential fitness benefits are greatest. Owing to paternal uncertainty, a father's kin may perceive fitness benefits as potentially lower than a mother's kin would and therefore reduce investment. Paternal certainty is considered a probable indicator of paternal investment in humans (Gaulin and Schegel 1980). In recent years, researchers expanded this idea to examine whether paternal certainty affects alloparental investment. A mother's kin tend to have higher certainty of genetic relatedness. Studies by Gaulin et al. (1997) and McBurney et al. (2002) have both shown a matrilateral bias in investment. Therefore, it is hypothesized that Aka infants who reside with their maternal kin will receive more alloparenting from all females than infants who reside with their paternal kin. Infants residing with their maternal kin will also benefit from greater allocaregiving owing to the long-standing reciprocal relationships that their mothers developed with other camp members. Hypothesis lb. Grandmother's investment will be higher among maternal grandmothers than among paternal grandmothers. Several recent studies suggest that paternal uncertainty plays a role in determining grandparental investment. Euler and Weitzel (1996) surveyed adults regarding grandparental solicitude during their childhood. Their results indicated that maternal grandmothers offered the most care followed in order by maternal grandfathers, paternal grandmothers, and finally paternal grandfathers. Most notably, the results indicated that residential distance, grandparental age, or availability of other grandparents did not influence grandparental care. Research in rural and urban Greece and Germany (Pashos 2000) has shown a paternal grandparent bias among rural Greeks and a maternal grandparent bias among urban Greeks. Pashos suggests that the social environment largely determines grandparental Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and Alloparental Investment 61 caregiving. Traditional rural Greek culture, with strong patrilineal ties, encourages a patrilineal bias in caregiving. He suggests that the maternal bias in urban populations could be related to the emergence of Western cultural norms in which females are more connected with their relatives than males. Although Pashos notes that paternal certainty is likely higher in patrilineal traditions, he states that paternal certainty does not in and of itself explain the paternal bias. However, McBurney et al. (2002) notes that in Pashos' study the paternal bias in caregiving is focused toward grandsons, which may simply be an extension of the patriarchal norms, and that the patriarchal system is likely overriding the matrilateral bias. Evidence also shows that maternal grandmothers invest more in their daughters' offspring than in their sons' offspring (Blurton Jones et al. 2005; Hawkes et al. 1997). Hawkes et al. (2000) suggest that while grandmaternal assistance directed toward a son's offspring could aid their own fitness, assistance directed toward daughters' offspring yields clearer benefits owing to genetic certainty. Hypothesis 2. Maternal caregiving will negatively correlate with alloparental caregiving. Given the assumption that alloparents enhance maternal reproductive success, mothers should redirect investment from current to future offspring if alloparental care is high and of good quality (McKenna 1987). THE AKAFORAGERS The Aka are an interesting case study for several reasons. First, they exhibit high levels of alloparental caregiving (Hewlett 1989, 1991b). In addition, residence patterns vary throughout a woman's reproductive career, affecting her access to maternal kin. Therefore, residence patterns can be used as a means of examining intracultural variability in alloparental caregiving. The Aka are tropical forest foragers and are primarily net hunters. The individuals represented in this study are associated with the Bangandou village of the Central African Republic. Aka live in camps of 25-35 individuals and often move camp several times a year. They live in association with the Ngandu, spending part of the year near the village to assist the Ngandu farmers. The Aka stress gender and intergenerational equality and have a minimal political hierarchy with few status positions (Bahuchet 1985; Hewlett 1991). Infertility is an infrequent problem among the Aka. The total fertility rate for postmenopausal women is approximately 5.5 (Hewlett 1991a). This rate is between those of other hunter-gatherer groups, such as the !Kung at 4.69 (Howell 1979) and the Ache at 8.03 (Hill and Hurtando 1996). The interval birth interval for Aka women averages 42 months, which again falls between those of other hunter-gatherer groups, such as the !Kung at 49.4 months (Howell 1979), the Yanomamo at 34.4 (Melancon 1982), and the Ache at 37.6 months (Hill and Hurtado 1996). Aka infants are raised in an intimate environment. Camps are built in a circle with all entrances to the huts facing the center of the camp. The huts 62 Human Nature / Spring 2005 have no doors and their small size limits the types of activities that can occur inside. Huts are only big enough to hold a four-foot-long bed and a fire and are usually placed within 1-2 feet of each other (Hewlett 2000a). Camp members perform most activities outside in view of other residents. Infants are therefore raised in a social unit that includes all members of a camp. Infants are held throughout most of the day and sleep in the same bed with their parents at night. Owing to the intensive daytime holding pattern and the size of the hut and bed, parents and caregivers provide almost constant skinto-skin contact for infants (Hewlett 1991a, 2000b). During the day, infants are generally held in a caregiver's lap or in a sling that rests on the mother's or alloparent's side. Infants are therefore able to see their caregivers and receive more continuous care than they would with other methods of holding. This high degree of physical contact also allows infants to breastfeed on demand. Nursing occurs several times an hour in short bouts. The level of physical contact also results in attention quickly being offered to fussing or crying infants (Hewlett 2000b). Mothers and allomothers quickly react with soothing, feeding, or nursing. The intimacy Aka infants have with juvenile and adult caretakers is unmatched in Western society and contributes to the high levels of alloparenting found in Aka society (Hewlett 1991a). The stable social units in which Aka children are raised allow the same individuals to interact with the children throughout their young lives. This environment creates an atmosphere in which alloparents have daily interactions with infants and observation of their cues. The Aka practice of brideservice allows for young women and often firsttime mothers to remain in their natal community during the period in which a mother and infant might require the most assistance. The period of brideservice usually lasts for a few years, approximately until the first child can walk (Hewlett 1991a; Shannon 1996). However, this period is quite flexible, and couples often move back and forth between camps during and after the traditional period of brideservice. Several circumstances can occur to disrupt the traditional period of brideservice. Men often need to leave their wife's camp and return to their natal community during the first several years of marriage for a variety of reasons, including desire to visit family members or a request from the husband's family for him to return. When this occurs, the wife's family often requests that their son-in-law return at a later date to finish his service. I asked many Aka men why they were conducting brideservice past the traditional time period, and while responses varied, many men laughed and sarcastically said, "Brideservice is never over." Women often will return to their natal community because they want to be closer to their family. One woman I spoke with said that she woke up one morning and told her husband that she wanted to live with her family for a while and left. She told me she knew her husband liked her and would follow, Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and Alloparental Investment 63 because he did not want to be away from her. He arrived in her parents' camp a few days later. Of the fifteen families represented in this study, three families resided matrilocally and two families resided patrilocally during the traditional period of brideservice. Of the families in which the men had finished brideservice or were continuing it past the traditional period, four resided matrilocally and six resided patrilocally. METHODS The foIlowing study is based on ten months of research, which was conducted over three field seasons from 2000 to 2002. Behavioral observations were conducted on 15 eight- to twelve-month-old infants (Table 1). Quantitative data were collected using a focal child sampling technique (Altmann 1974). This involved observing the focal child and recording specific behaviors and interactions. Observations were cued using a tape recorder and earphone, and recorded on handheld data sheets. Infants' behaviors and the behaviors that caregivers directed toward them were observed every 20 seconds. Each 20second interval concluded with a 10-second interval to record the observed behaviors. These behaviors were recorded on-the-mark as instructed by the tape recorder. Observations were conducted over a 12-hour daylight period (6:00 AM - 6:00 PM). Every 45 minutes of observation was followed by a 15-minute break. Observation periods were divided into four 3-hour sessions, and infants were observed over several days to enable the observation of multiple activities. The combined observation period for all of the focal infants totaled 135 hours. All of the infants were observed for 9 hours, which yields 1,080 intervals per infant or 16,200 total intervals for all 15 infants. The behavioral observations recorded infant visual orientation, infant state, caregivers' response to infants' distress, infant behaviors, and caregiver behavior directed toward infant. The Aka do not have birth records, nor do they keep of track of age. The age of the infants was determined by season of birth, dentition, and relative aging of other infants in camp or from nearby camps. Since the target infants were all less than a year old, the season of birth quickly determined if they were below the minimum of eight months or above the maximum of one year. Dentition varied far more than originally expected; however, infants' ages were verified through relative dating using the infants' birth orders. The data presented in this paper represent all infant and caregiver activities observed during daylight hours. Therefore, the data set offers a full picture of infant and caregiver behavior in various settings. Infants were observed with their caregivers in their camp, in the forest, on net hunts, and in the village. Mothers and other caregivers continued their daily routines during the observation periods. Qualitative data were also collected on the focal infants' mothers. I used semi-structured interviews to elicit information on maternal preferences for locality and their perceptions of alloparental assistance. ..M.- 0 J~ Q; Q; o Q; 0 0 o r~ 0 0 ..0 d e~ o 0 0 ~ ~~ ~ ~ o r,.) ~ ~ ~ ~ Z ~ ~__ -I-- -I~ 0 Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and AIIoparental Investment 65 Coding Caregivers Caregivers were coded by sex and age categories. The six categories were juvenile, adult, and elderly males and females. Individuals who were under the age of 18 were coded as juvenile males and females. Because the Aka do not keep track of their age, the marital status of young men and women was used to approximate age. Therefore, most individuals who were not married and had no children were coded as juveniles. The adult category was used if a male or female was married or had children. The few adults who were unmarried or did not have any children were coded based on obvious age cues. Almost every adult female in both matrilocal and patrilocal camps had dependent children. Menopause and grandparental status determined the elderly category. Siblings were also coded by their age and sex but were analyzed separately unless otherwise noted. Additionally, caregivers were given identification codes, and relationships between caregivers and the focal infants were coded. Relationships were determined through detailed demographic information collected prior to the commencement of the behavioral observations or through subsequent interviews if the caregiver was a visitor. This recording system also enabled the coding of simultaneous interactions with an infant by individuals in the same age and sex category to be recorded. High- and Low-Investment Caregiving Researchers have examined infant caregiving behaviors in terms of direct and indirect care. Direct caregiving behaviors encompass activities such as holding and feeding, while indirect caregiving behaviors are those that relate to foraging for food or territory defense (Kleiman and Malcolm 1981; Marlowe 1999, 2005). The methodology of this study precluded recording of data on indirect care; therefore, the focus will be on direct caregiving. Since the category of direct care includes all behaviors that require close proximity to infants, I divided it into two distinct categories to distinguish between high-investment and low-investment caregiving. High-investment caregiving behaviors require intimate contact or direct attention to the infant. The behaviors included in high-investment caregiving are holding; soothing; medical, hygienic, and general caregiving; feeding; nursing; stimulating the infant; playing with the infant; and affectionate behaviors directed toward the infant. While soothing does not always require intimate contact with the infant, this behavior is purposefully directed toward the infant and often interrupts the caregiver's other activities. Low-investment behaviors are classified as those that result in minimal energy expenditure. Behaviors included in the low-investment category are watching or checking on the infant, vocalizing to the infant, touching, and proximity to the infant. Low-investment behaviors are those in which caregivers can continue other tasks with ease. Touching was coded as low- 66 Human Nature / Spring 2005 investment care in order to avoid overestimating the frequencies of highinvestment caregiving. Touching could at times be included as intimate contact and often was purposefully directed toward the infant. However, because the Aka sit in close proximity to each other, it was difficult to establish intentionality for every instance of the behavior. Another example of low-investment care is proximity. Proximity does not necessarily require any investment; it is defined here as being a forearm's distance from the focal infant. Nevertheless, caretakers within proximity would be more likely to offer allocare and high-investment caregiving when needed. Each caregiving behavior is independent of other behaviors. For example, a caregiver holding an infant (which includes touching) would only be coded as holding. On occasion, single behaviors, such as holding, will be discussed for comparative purposes, but these individual variables to do not show a complete picture regarding the depth of care offered. RESULTS Variability in Demographic Features across Residence Patterns Most Aka families eventually take up permanent residence in the husband's camp. The likelihood of patrilocality increases with age and the number of children the couple has together. Each of the four couples with four children in this sample was residing patrilocally. Table 2 shows a comparison of demographic variables by residence pattern. Thirteen camps are represented in this study. Camp size was consistent in most of the focal infant camps, and there are no significant differences in camp sizes between matrilocal and patrilocal settings. The mean number of individuals in a camp was 25.6 people. The minimum number of individuals in a camp was 14 and the maximum was 35. Camps along logging roads are much closer to one another than camps in other settings, and camp sizes tend to be larger. However, for the families represented here, no significant difference in camp size or the level of alloparenting exists based on the setting of a camp in the forest, village, or along a logging road. No significant difference exists between the number of an infant's siblings at the matrilocal and patrilocal camps (Table 2). The distribution of male and female infants across the two camp settings is also equal (Fisher's exact test: r = 0.1964, p = .405). Infants also have access to a similar number of potential female caretakers in matrilocal (12.42) and patrilocal (10.25) camps. However, the average number of females in matrilocal camps who participated in allocare (15.29) is significantly higher than in patrilocal camps (8.25). Frequency of Behaviors The remaining results in this paper are discussed in terms of the frequency of behaviors rather than the amount of time caregivers spend assisting infants. ~ . -= e~ o ~- ~__. < ~0 0 < 0 =~ e,i V .x- 68 Human Nature / Spring 2005 The frequencies of behaviors offer a picture of the depth of care offered to infants. For example, if only the amount of time is examined, an infant who is sitting on its mother's lap for a half an hour while the mother cooks dinner would be shown as receiving equal caregiving as an infant who was being held by one juvenile female, fed by another, and washed by a third during the same period. Since an infant commonly interacts with multiple caregivers in one interval, the frequencies reported in the following results represent multiple individuals and multiple independent caregiving behaviors within each interval. Therefore, the frequencies are presented as the number of caregiving behaviors directed to the infant and include multiple interactions within single intervals. Do Infants Receive More Allocare from Matrilineal Kin ? The average frequency of caregiving behaviors by juvenile and adult female allocaregivers is higher in all caregiving categories in matrilocal as compared to patrilocal camps. Juvenile and adult females show significant or very strong trends toward higher levels of matrilocal alloparenting for most individual caregiving behaviors as well. In matrilocal camps, juvenile and adult females are more than twice as likely to be in close proximity to the infant (Mann-Whitney U = 11.00, p = 0.054). The frequency of non-sibling, juvenile and adult female holding is close to five times as great in matrilocal camps (Mann-Whitney U = 8.5, p = 0.021). Infants living matrilocally receive 2.5 times more physical contact (holding and touching) from juvenile and adult female allocaregivers (Mann-Whitney U = 10.00, p = 0.40). Most infants living patrilocally did not receive caregiving from adult females. Women living in the infant's father's camp were not likely to touch (Fisher's exact test: r = .7888, p < .01), or hold (Fisher's exact test: r = .6001, p < .05), focal infants. When behavioral categories were examined collectively (high- and lowinvestment caregiving), the two localities demonstrate a significant difference in the frequency of allocare. Infants living in matrilocal camps receive 3.4 times more high-investment caregiving from juvenile females (matrilocal mean = 62.71, patrilocal m e a n = 18.62) and 6.4 times m o r e h i g h - i n v e s t m e n t caregiving from adult females (matrilocal mean = 28.86, patrilocal mean = 4.50). In Table 3, the average frequencies of caregiving behaviors of juvenile and adult females are presented in terms of high- and low-investment care and are then combined to show an overall trend of total care given to infants. When juvenile and adult female alloparents are analyzed together, high- and low-investment and total caregiving are significantly different between the two samples (Table 3). Given the practice of brideservice and the assumption that first-time mothers reside with their kin, one might assume that infants whose families are residing matrilocally receive more care because of heightened risk factors as- ~ ~ ~ ~ '~ t"-. ~ t= 0 ~a I= ,< o >,, 0 e~ 0 r ,,8 ..& 0 0 ~ ~ ~ t~ t' ~ '~ 70 Human Nature I Spring 2005 sociated with first-time mothers (Hrdy 1976). However, this sample does not show a bias toward matrilocality for primiparous mothers (Fisher's exact test: r = .189, p = .4266). In both residential patterns adult females showed higher frequencies of high-investment caregiving, but it was not significant at the .05 level. Comparison of All Non-Sibling Female Alloparents Table 3 also examines the differences in investment by non-sibling female (juvenile, adult, and elderly) alloparents based on residence pattern. The overall frequency of high-investment, low-investment, and total care offered to Aka infants is higher in matrilocal camps. However, female high-investment care is not significantly different by camp setting--but this includes the investment by an unusually high investing paternal grandmother (which will be discussed in more detail below). Her caregiving was the highest of all non-maternal caregivers and was quite unusual. If she is removed from this sample, matrilocally residing infants receive significantly more care from non-sibling matrilocal females (Mann-Whitney U = 7.00; p = .026). Even with this grandmother included, infants received significantly more low-investment caregiving and significantly more total (high- and low-investment) caregiving when the family is residing matrilocally. Sibling Investment The frequency of Aka sibling care is not significantly different based on whether the family is residing matrilocally or patrilocally (Table 3). As shown above, patrilocal families have on average more offspring, although the difference is not statistically significant. In both residence patterns, Aka siblings participate in allocare, but they participate less than other female caregivers combined. The lack of significance is expected. Sibling caregivers regardless of camp locality have strong relationships with their mothers and siblings. In addition, forager siblings tend to invest less overall than do siblings in farming societies (Hewlett 1991b). Paternal Investment Aka fathers are known throughout the hunter-gatherer and parental investment literature for their high levels of investment (Hewlett 1991a). However, when paternal investment is examined by residential pattern (Table 3), they show a trend of engaging in high-investment caregiving more in their own camps than when residing with their wife's family (Table 3). Aka fathers in their natal groups also show a trend, albeit not significant, toward holding their infants more than fathers living in their wife's camp. When residing in their natal camps, fathers hold their infants 6.1% of its total holding time, compared Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and Alloparental Investment 71 with 1.0% of the total holding time when the fathers are living in their wife's camp. The overall averages of paternal holding are lower than Hewlett's data of 8.7% because three fathers, two in the patrilocal category and one in the matrilocal category, left on trips during the observation period. This probably explains the lowered overall level of paternal investment recorded. However, there is variation between camp settings. Aka fathers seem to be offering less paternal investment when they reside in their wife's camp. The frequency of high-investment, low-investment, and total care offered by fathers is significantly lower in matrilocal settings. Female Preference for Locality Each of the focal infants' mothers was asked to discuss the level of assistance that she received at her current location. Assistance was categorized as sharing (food, water, or other items) and childcare assistance. Women were also asked to discuss who their friends were and what qualities of a friend were important. It was originally hypothesized that women living matrilocally would report greater assistance both from kin and non-kin in their communities. The high certainty of genetic relatedness to the infant combined with long-term relationships between the mother and potential caregivers would lead to a reduction in the cost of allocate on the part of the caregiver. All but two of the fifteen mothers said they would rather live in their parents' camp when they had a child because they stated they receive higher levels of assistance. The assistance was always attributed to the mother's parents and siblings. Women (n -- 5) whose mothers were deceased stated that they would rather live at home because of paternal and sibling assistance. One of the women who said it did not matter where she resided had been living in her husband's camp for a long time. She had three other children besides the focal infant, plus children from a previous marriage. Thus she was an experienced mother and caregiver. The other woman who stated that residence did not concern her was interviewed in front of individuals from her husband's family. This was their first child, and while her comments to other questions were forthright, she became quite distant and quiet during this part of the interview. It is possible she felt uncomfortable stating that the assistance she received from other women was not equal to what she might get at home. However, many other women answered this question openly in front of their husband's kin, and no one seemed to take offense at the answer. Other women sitting close by would often add their opinions as well. Subjective reports from the interviews supported the findings from the behavioral observations. Women defined friends as individuals who gave things or shared food and other items with them. Women in both camp settings stated that jealousy was a constant strain on friendships. Friendships were accompa- 72 Human Nature I Spring 2005 nied by considerable gossiping, which caused problems with the other women in camp. Not surprisingly, women in their husband's camps, where female kin did not surround them, felt that they did not have as many friends as they did when they resided in their own parents' camp. In both settings, women claimed difficulty in establishing non-kin friendships. Even women living matrilocally usually listed their sisters, cousins, or other female relatives as those individuals with whom they had a friendship. However, when questioned regarding non-sibling friends, women living in their natal communities could mention at least one woman. The number of friends listed depended on age. Of the five youngest mothers--those who had only one child--three lived in their own family's camp and two lived in their husbands'. All three of the matrilocally residing mothers named between two and five friends. One of the mothers living in her husband's camp named four friends and the other named none. The former woman did not live close to her parents' camp; she had known all of the women she listed as friends from her youth, and they lived in surrounding camps. Women explained that as they got older it was more difficult to keep friendships. In cases regarding older women and/or those living with their husbands' families, the friends they mentioned were individuals from their past who lived in their natal community. Those women who did have female friends (n = 8) stated that friends were good to have because you could leave your infant with them (if the father was not present) when you went to collect water or firewood. Aka mothers rarely leave an infant with either kin or non-kin for an extended period of time, but neither of those tasks requires a lengthy investment by the alloparent. Do Maternal Grandmothers Invest More Than Paternal Grandmothers? The importance of grandmaternal investment has been used to explain long postmenopausal lifespans, as well as impacts on maternal fertility and infant survivorship (Hawkes 1997). In particular, maternal grandmothers offer the most support, although patrilocal residence patterns would minimize the assistance that maternal grandmothers could offer. Hawkes et al. (2000) suggest that variation in residence patterns is substantial, and among non-equestrian, non-fishing-dependent hunters, matrilocal residence patterns are not uncommon. Marlowe (2005) notes that among the Hadza, 68% of couples with living mothers reside in the camp with the wife's mother. This variation could help explain periods of matrilocality, such as among the Aka, whereby women can receive the support of their mothers when they most need it. Evidence shows that grandmothers direct assistance to the daughters that require the most aid (Blurton Jones et al. 2005, Hawkes et al. 1997). The sample size in this study limited the analysis on elderly female participation in infant care. Nevertheless, the following analysis seeks to examine Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and Alloparental Investment 73 grandmaternal caregiving. Some of the infants lacked grandmothers (n = 8) or other elderly females in camp. Eleven of the fifteen Aka infants had an elderly female present in camp. Of the eleven elderly females, seven were actual grandmothers. Three of the seven were maternal grandmothers and four were paternal grandmothers. The following analysis will focus only on grandmothers because elderly female participation in caregiving was rare if they were not the actual grandmother. Aka infants received similar care from grandmothers in both residential patterns. No significant difference existed between elderly female high- and lowinvestment or total care. Interestingly, the highest investing grandmother was a paternal grandmother. Her high-investment caregiving frequencies were more than double those of the next highest investing grandmother, who was a maternal grandmother. However, there were several unique factors surrounding this grandmother and infant. First, the infant fussed and cried frequently. Much of the grandmother's caregiving behavior was directed toward soothing the infant or actively trying to keep the infant from starting to cry. The infant's fussing and crying frequency (140.0) was more than double the sample average (52.73). Second, this was her daughter-in-law's first child and she was living with her husband's family, which is unusual. In addition, the mother was most likely the youngest mother in the sample. She had less experience with caregiving than other women, who often have one or two children before they permanently reside in their husband's family camp. Primiparous mothers have been associated with increased risk factors for child mortality (Hrdy 1976). I noted several occurrences of this grandmother offering to help her daughter-in-law after she had been unsuccessful at soothing the infant. The infant's distress was not related to any visible illness. She was a healthy, plump infant, but very aggressive. She would often push or thrash at her caregiver. This paternal grandmother was undoubtedly a high-investing grandmother, often taking some of the responsibility away from her new daughter-in-law, who obviously needed help with a very fussy infant. All three of the infants who resided in the same camp as their maternal grandmother received high-investment care from them; however, only two of the four infants residing with their paternal grandmother received any highinvestment care from their grandmothers. The three maternal grandmothers directed 63, 133, and 151 high-investment behaviors toward their grandchild over the observation period. Of the four paternal grandmothers, two offered no high-investment care, one directed 28 high-investment behaviors toward their grandchild, and the final paternal grandmother offered 360 high-investment behaviors. Given the obvious problems with such a small sample of grandmothers, and the tremendous difference between the paternal grandmother discussed above and the other paternal grandmothers, further research will be needed to address this question. 74 Human Nature / Spring 2005 Do Mothers Reduce Investment in Infants When Allomothers Are Available or When the Frequency of Alloparenting Is High? While significant differences in allocare are prevalent among female alloparents and fathers, no significant difference exists in maternal caregiving. Mothers on average offer lower frequencies of caregiving in matriiocal camps, but statistically it is not different from average investment in patrilocal camps. Maternal high-investment care, low-investment care, and the total frequency of maternal caregiving did not differ significantly based on residence pattern. According to the second hypothesis, which suggested that maternal investment would be negatively correlated with alloparental investment, alloparenting should reduce the overall time that mothers must spend caregiving. Among nonhuman primates, maternal kin most frequently provide alloparenting (Hrdy 1981), and mothers that receive allocare for their infants are able to spend more time away from their infants (Fairbanks 1990). The methodology in this paper (focal infant follows) precludes any analysis regarding maternal behavior while they are not visible or engaged in childcare, but the assumption is that high levels of positive allocate will enable the mother to pursue other economic activities. In order to examine this hypothesis, sibling care, the number of participating females, alloparental investment, and total care by all individuals were examined for correlations with maternal behavior. No significant correlations exist between any of these variables and maternal investment in either camp setting. However, mothers residing in their natal camps show trends of reducing low-investment behaviors (Pearson r = -0.706, p = .077) and overall investment (Pearson r = -0.730, p = .062) when high levels of direct female alloparental care are given to the infant. This trend is not apparent in patrilocal settings. Do Infants Residing Matrilocally Receive Higher Frequencies of High- and Low-Investment Caregiving ? The total frequencies of caregiving that infants receive from mothers, fathers, and all other caregivers in matrilocal and patrilocal camps are remarkably similar considering the variability found in the age/sex categories. Table 4 illustrates the total frequency of Aka caregiving, including maternal caregiving the infants received, dependent on residence pattern. Although male alloparents were not analyzed separately, because of their overall low level of investment, Table 4 includes them in order to examine the total amount of care infants received. High-investment caregiving and total allocare offered are not significantly different in matrilocal and patrilocal camps. Low-investment caregiving shows a trend, albeit not significant, for higher frequencies in matrilocal settings (Mann-Whitney U = 10.29, p = .072). However, it should be noted again that low-investment caregiving is less costly to the alloparent, and most of the difference is due to proximity. 0 0 ~ c~ c~ o 9 E CL~ o 9 ~ r~ c~ ~,JD ~ c~ O c~ O ,mq 76 Human Nature / Spring 2005 DISCUSSION The analyses show significant differences in alloparental care among the Aka, indicating a matrilateral bias. Hypothesis l a suggested that infants would receive greater frequency of high-investment allocare if they resided in their mother's camp. Infants residing matrilocally have significantly more alloparents and receive higher frequencies of caregiving behaviors from maternal kin. The interview data also supported this hypothesis that when long-standing reciprocal relationships between a mother and camp members are present, female allocare will be higher in frequency. Since first-born infants do not receive significantly more care from female alloparents in either matrilocal or patrilocal camps, the hypothesis of parity influencing alloparental investment is not supported. Therefore, the question needs to be examined not in terms of maternal inexperience (i.e., infant need) but through the mother/alloparent relationship and the infant/alloparent relationship. For Aka infants residing matrilocally, paternal investment is minimal but female alloparental investment is remarkably high. For Aka infants residing patrilocally, paternal investment is high but female alloparental investment is quite low. Three avenues of explanation are possible. First, fathers are relieved from childcare responsibilities in matrilocal camps because of the willingness of female alloparents to offer assistance. Second, female alloparents offer higher frequencies of care to infants residing matrilocally owing to high certainty of genetic relatedness. Third, female alloparents offer higher frequencies of ailoparental care in matrilocal camps because they detect a deficiency in paternal investment. Fathers living in their spouse's camp are often doing brideservice. Young husbands are hard to find during the day, as they leave early and come home late in order to avoid being asked to work by the wife's family (Hewlett, personal communication 2003). This may be one factor that contributes to their lower level of investment. Mothers living in their own camps also have multiple female kin with whom they conduct subsistence activities. An absent husband would not likely decrease their overall foraging success, especially in regards to female kin's foraged food items. Hewlett (1991b) suggests that the lower levels of paternal involvement may be due to the availability of other adult females to assist with childcare. It is possible that the same pattern of willing female caretakers in matrilocal camps is allowing lower levels of paternal investment than are found among fathers in patrilocal camps. However, this last possible avenue of explanation does not explain the lack or low level of investment by female alloparents residing in patrilocal camps. It seems more reasonable to consider paternal certainty as an influencing factor for nongrandparental female allocare. Hypothesis lb suggests that maternal grandmothers invest more than paternal grandmothers. This hypothesis was not supported. Grandmothers' investment seemed to be equal across residential patterns. However, as mentioned Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and Alloparental Investment 77 above, the high-investing paternal grandmother was quite unusual and her circumstances were not common owing to the Aka practice of brideservice. Further research with a larger sample of grandmothers will be needed to examine this issue. Hypothesis 2, suggesting that maternal caregiving should be lower when high levels of alloparenting are given to infants, was also not supported. Maternal behavior across residence patterns was consistent with overall averages of maternal investment, and the variation that exists is predictable. This study did not statistically demonstrate a direct correlation between high frequencies of alloparental behavior and a reduction in maternal frequencies of caregiving. However, maternal behavior in matrilocal camps shows a trend of reducing low-investment and total care levels when the infant received more highinvestment female alloparenting. If alloparents are aiding maternal reproductive success through other means by allowing them to shift strategies, these avenues need to be explored. The methodology of the study (focal infant follows) did not allow reliable data on maternal workload and foraging success. Future research should examine whether alloparents increase maternal reproductive success and decrease interbirth intervals. While the data show that alloparental assistance is higher from maternal kin, it also shows that infants have numerous avenues for receiving care. The similar overall averages of caregiving by mothers, fathers, siblings, and all alloparents in matrilocal and patrilocal camps suggest that alloparents' investment strategies take into account multiple socioecological factors, including the relationship to the mother and paternal certainty. Parental, sibling, and alloparental care equalized caregiving frequencies and, in the end, showed levels that were standard and culturally acceptable. In both camp settings mothers repeatedly stated that they would prefer to live with their kin when they have a young child. This preference might illustrate that while the overall levels of caregiving are equal, having multiple caregivers may be beneficial to the mother and infant. In matrilocal camps, mothers have multiple options for additional caregivers; thus they are more likely to have an available alloparent at any given moment. Ivey (2000:864) notes that the number of alloparents available to an infant is positively correlated with infant survivorship. While individual caregivers certainly have high levels of investment, the availability of multiple caregivers can insure that an infant always has access to investment. Close association with maternal kin is likely to be helpful to the mother and infant, but future research may determine the exact effect on Aka maternal reproductive success and infant survivorship. I am indebted to the Aka families who allowed me to live and work with them. I would also like to thank the government of the Central African Republic for authorizing my research. I offer my thanks to Barry S. Hewlett for his advice and assistance and to Hillary Fouts, who helped me in the early stages of this research project. 78 Human Nature [ Spring 2005 Courtney L. Meehan is a Ph.D. student in cultural anthropology at Washington State University. Her research interests include parenting, alloparenting, female social networks, and female-female cooperation and competition. REFERENCES Altmann, J. 1974 Observational Study of Behavior: Sampling Methods. Behaviour49:227-267. Bahuchet, S. 1985 Les Pygmees Aka et la Foret Centrafricaine. Pads: Selaf. Bereczkei, T. and R. I. M. Dunbar 2002 Helping-at-the-Nest and Sex-Biased Parental Investment in a Hungarian Gypsy Population. Current Anthropology 43:804-810. Blurton Jones, N. 1993 The Lives of Hunter-Gatherer Children. In Juvenile Primates, M. Perreira and L. Fairbanks, eds. Pp. 309-326. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Blurton Jones, N., K. Hawkes, and J. O'Connell 2005 Hadza Fathers and Grandmothers as Helpers: Residence Data. In Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods, B. S. Hewlett and M. E. Lamb eds. Piscataway: AldineTransaction, in press. Bowlby, J. 1969 Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books. Elmen, S. T. 1982a TheEv~uti~n~fHe~ping~:AnF~ca~C~nstraintsM~de~.AmericanNatura~ist~9:29-39. 1982b The Evolution of Helping, 2: The Role of Behavioral Conflict. American Naturalist 119:4053. 1994 Benefits, Constraints, and the Evolution of the Family. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 9:282-285. Euler, H. A., and B. Weitzel 1996 Discriminative Grandparental Solicitude as Reproductive Strategy. Human Nature 7:3959. Fairbanks, L. A. 1990 Reciprocal Benefits of Allomother for Female Vervet Monkeys. Animal Behavior 40:553562. Flinn, M. 1989 Household Composition and Female Reproductive Strategies in a Trinidadian Village. In The Sociobiology of Sexual and Reproductive Strategies, A. E. Rasa, C. Vogel, and E. Voland, eds. Pp. 206-233. London: Chapman and Hall. Gaulin, S. J. C., and A. Schiegel 1980 Paternal Confidence and Paternal Investment: A Cross-Cultural Test of a Sociobiological Hypothesis. Ethology and Sociobiology 1:301-309. Gaulin, S. J. C., D. H. McBumey, and S. L. Brakeman-Wartell 1997 Matrilateral Biases in Investment of Annts and Uncles. Human Nature 8:139-151. Hawkes, K., J. E O'Connell, and N. G. Blurton Jones 1997 Hadza Women's Time Allocation: Offspring Provisioning and the Evolution of Long PostMenopausal Lifespans. Current Anthropology 38:551-557. Hawkes, K., J. F. O'Connell, N. G. Blurton Jones, H. Alvarex, and E. L. Charnov 2000 The Grandmother Hypothesis and Human Evolution. In Adaptation and Human Behavior: An Anthropological Perspective, Lee Cronk, Napoleon Chagnon and William Irons, eds. Pp. 237-258. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Hewlett, B. S. 1989 Multiple Caretaking among African Pygmies. American Anthropologist 91:186-191. 1991 a IntimateFathers: The Nature and Context ofAka Pygmy Paternal Infant Care. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 1991b Demography and Childcare in Preindustrial Societies. Journal of Anthropological Research 47:1-37. Effects of Residential Locality on Parental and Alloparental Investment 79 Hewlett, B. S., M. E. Lamb, B. Leyendecker, and A. Scholmerich 2000a hatemal Working Models, Trust, and Sharing among Foragers. Current Anthropology 41:287-297. 2000b Parental Investment Strategies among Aka Foragers, blgandu Farmers, and Euro-American Urban-Industrialists. In Adaptation and Human Behavior: An Anthropological Perspective, L. Cronk, N. Chagnon and W. Irons, eds. Pp. 155-178. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Hill, K., and A. M. Hurtado 1996 Ache Life History: The Ecology and Demography of a Foraging People. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Howell, N. 1979 Demographyof the Dobe !Kung. New York: Academic Press. Hrdy, S. B. 1976 The Care and Exploitation of Non-human Primate Infants by Conspecifics Other Than the Mother. In Advances in the Study of Behavior, vol. 6, J. Rosenblatt, R. Hinde, and C. Beer, eds. Pp. 101-158. New York: Academic Press. 1981 The Woman That Never Evolved. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1999 Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants and Natural Selection. New York: Pantheon Books. 2005 Comes the Child before Man: How Cooperative Breeding and Prolonged Post-Weaning Dependence Shaped Human Potentials. In Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods, B. S. Hewlett and M. E. Lamb, eds. Piscataway: AldineTransaction, in press. Ivey, P. K. 1993 Life History Perspectives on Allocaretaking Strategies among Efe Foragers of the ltuH Forest of Zaire. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico. 2000 Cooperative Reproduction in the lturi Forest Hunter-Gatherers: Who Cares for Efe Infants? Current Anthropology 41:856--866. Kleiman, D. G., andJ. R. Malcolm 1981 The Evolution of Male Parentallnvestment in Mammals. In Parental Care in Mammals, D. J. Gubemick and P. H. Klopher, eds. Pp. 347-388. New York: Plenum. Kramer, K. L. 2002 Variationin Juvenile Dependence:HelpingBehavioramong MayaChildren. Human Nature 13:299-325. Marlowe, F. 1999 Showoffs or Pmviders?The ParentingEffort of HadTnMen. Evolutionand Human Behavior 20:391--404. 2005 Who Tends Hadza Children? In Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods, B. S. Hewlett and M. E. Lamb, eds. Piscataway: AldineTransaction, in press. Melancon, 3". 1982 Marriage and Reproduction among the YanomamoIndians of Venezuela. Ph.D. dissertation, Pennsylvania State University. McBurney, D. H., L Simon, S. L C. Gaulin, and A. Getiebter 2002 Matrilateral Biases in the Investment of Aunts and Uncles: Replication in a Population Presumed To Have High Paternity Certainty. Human Nature 13:391-402. McKenna, J. J. 1987 Parental Supplements and Surrogates among Primates: Cross-Species and Cross-Cultural Comparisons. In Parenting across the Life Span: Biosocial Dimensions, J. B. Lancaster, J. Altmann, A. Rossi, and L. Sherrod, eds. Pp. 143-186. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Pashos, A. 2000 Does Paternal Uncertainty Explain Grandparental Solicitude? A Cross-Cultural Study in Greece and Germany. Evolution and Human Behavior 21:97-109. Sear, R., R. Mace, and I. A. MacGregor 2003 The Effects of Kin on Female Fertility in Rural Gambia. Evolution and Human Behavior 24:25--42. Shannon, D. 1996 EarlyInfant Care among the Aka. M.A. thesis, Washington State University, Pullman. 80 Human Nature / Spring 2005 Solomon, N., and J. French 1997 The Study of Mammalian Cooperative Breeding. In Cooperative Breeding in Mammals, N. Solomon and J. French, eds. Pp. 1-10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stacey P., and W. D. Koenig 1990 Cooperative Breeding in Birds: Long-Term Studies in Ecology and Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Strassman, B. I., and A. L. Clarke 1998 Ecological Constraints on Marriage in Rural Ireland. Evolution and Human Behavior 19:33-56. Tronick, E. Z., G. A. MoreUi, and P. K. lvey 1992 The Efe Forager Infant and Toddler's Pattern of Social Relationships: Multiple and Simultaneous. Development Psychology 28:568-577. Tronick, E. Z, G. A. Morelli, and S. Winn 1987 Multiple Caretaking of Efe (Pygmy) Infants. American Anthropologist 89:96-106. Turke, P. 1988 Helpers at the Nest: Childcare Networks on Ifaluk. In Human Reproductive Behaviour: A Darwinian Perspective, L. Betzig, M. Borgherhoff Muider, and P. Turke, eds. Pp. 173-188. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Weisner, T. S. 1987 Socialization for Parenthood in Sibling Caretaking Societies. In Parenting across the Life Span: Biosocial Dimensions, J. B. Lancaster, J. Altmann, A. Rossi, and L. R. Sherrod, eds. Pp. 237-270. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Weisner, T. S., and R. Gallimore 1977 My Brother's Keeper: Child and Sibling Caretaking. Current Anthropology 18:169-190. Williams, G. C. 1966 Adaptation and Natural Selection. Princeton: Princeton University Press.