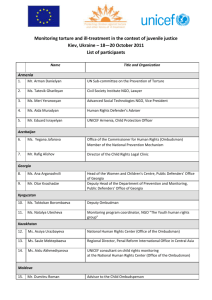

Background Paper - Financial Ombudsman Service

advertisement