Jackson vs. the Bank

advertisement

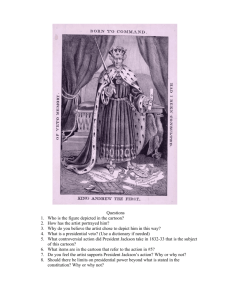

Jackson vs. the Bank In vetoing a renewed charter for the Second Bank of the United States, Andrew Jackson challenged both Congress and the Supreme Court. 58 Leading antagonists in the struggle were President Jackson (far left) and the Bank’s president, Nicholas Biddle, a wealthy Philadelphian. Above: note issued by the Second Bank the United States after it received a Pennsylvania state charter. I t was early July 1832. Debilitated by the hot, sticky Washington weather, Andrew Jackson had taken to his bed. Martin Van Buren found him there, looking like a “spectre.” The President reached out his hand to his former secretary of state. “The bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me,” he cried out, “but I will kill it!” The bank Jackson intended to destroy was the Second Bank of the United States, the successor to a national bank chartered by Congress in 1791. Jackson was firmly convinced that the Bank was unconstitutional, and in vetoing its recharter, he raised a provocative constitutional issue, one that has never been adequately addressed. Specifically, Jackson challenged the right of the Supreme Court to have the last word on the meaning of the Constitution. CONSTITUTION/FALL 1990 Jackson opposed the Bank on other than constitutional grounds as well, and said so in his veto. The Bank of the United States created an aristocracy of money, he believed. That the government should grant this institution exclusive privilegespermitting the few to be made richer at the expense of the majority—and that this powerful Bank could and did purchase political influence, struck him as “dangerous to the liberties of the people.” Strict constructionists of the day were appalled that Jackson would raise economic, social or political justifications for a veto. Hitherto, Presidents had vetoed legislation on constitutional grounds only. By raising other issues, Jackson in effect claimed for the chief executive the right to participate in the legislative process: henceforth, before enacting any measure, 59 Jackson had been a roughneck, “the most roaring, rollicking, game-cocking, horse-racing, card-playing …” fellow in his community. Congress would have to assess the President’s wishes or risk a veto. The First Bank of the United States had been proposed by Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the treasury under George Washington, as part of his program to set the new nation on a sound financial footing. Hamilton envisioned a central banking system with a parent bank in Philadelphia and branch banks in the country’s principal cities; the branches would serve as depositories for government funds and act as agencies in the collection of taxes. The Bank was to be chartered by Congress for 20 years and was permitted a capital stock of $10 million. Onefifth of this sum would be subscribed by the government and four-fifths by private investors, both American and foreign. The corporation would be managed by a president and a board of 25 directors, five of whom would be appointed by the federal government and 20 elected by the stockholders. Both James Madison and Thomas Jefferson opposed Hamilton’s proposal, arguing that none of the powers delegated to Congress by the Constitution warranted the creation of such an institution. To contend, as Hamilton did, that the ability “to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper” implied that Congress had the power to authorize a national bank was to grant Congress dangerously elastic powers. Over their fierce objections, a bill establishing the First Bank of the United States squeezed through Congress, and President Washington signed it. Twenty years later, in 1811, the Bank’s charter expired. Renewal was defeated in Congress by a narrow margin, and the institution slipped out of existence. Madison was then President, but what killed recharter was the opposition of state banks. They had found the power and authority of the First Bank oppressive, for it was able to insist that state banks keep enough gold and silver on hand to cover their debts to the government, and this restraint kept them from lending out all the money they chose. There was also concern about foreign ownership of the Bank’s stock at a time of peril in Europe, brought about by the Napoleonic Wars. Without the institution, the nation embarked on the War of 1812 lacking adequate financial backing. The resulting economic chaos convinced even the reluctant Madison that a national bank was essential, and in 1816 he signed the necessary legislation to charter the Second Bank of the United States, with a capital stock of $35 million. The question of the Bank’s constitutionality continued to be controversial and was tested, in 1819, in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland. The circumstances of the case were these: when the speculative activities of its president, William Jones, led to the Second Bank’s near failure, the institution adopted a policy of fiscal stringency. This, to a large extent, precipitated the Panic of 1819. In turn, many states retaliated against the Bank’s crippling control of credit. Two states forbade it to operate within their borders; six others taxed its branches. Maryland was one of these. The state’s counsel, believing that the powers of the national government were subordinate to the sovereignty of the states, argued that the Bank was illegal and that Congress had no authority to establish a national bank. But Chief Justice John Marshall ruled otherwise, delivering an opinion so influential one scholar likened its importance to that of the Constitution itself. Marshall declared that the Constitution not only spelled out the powers of Congress, but in the “necessary and proper” clause gave Congress the power to accomplish any legitimate government aim: “Let the end be legitimate ... and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.” With its legal status settled, the Bank prospered during the 1820s under the directorship of a new president, Nicholas Biddle. Born to a wealthy Philadelphia family, the extraordinarily talented young man had graduated at the age of 15 as class “Andalusia” on the Delaware River outside of Philadelphia, was the country seat of Nicholas Biddle. In 1839, Biddle retired there and often welcomed an array of intellectuals and European exiles, who came to discuss politics and the classics with one of America’s most cultivated figures. 60 valedictorian from the College of New Jersey at Princeton. (He had previously completed all the requirements for a degree from the University of Pennsylvania, but because he was only 13 at the time, the university refused to grant him a diploma.) He studied and traveled abroad, married the socially prominent Jane Craig and indulged his taste for literature and Greek art at “Andalusia,” his wife’s family home. Strikingly handsome, Biddle was a cultivated, highly intelligent and strong-willed man of great personal charm—and he became an extremely knowledgeable banker. President James Monroe appointed him as one of the government’s five directors of the Bank, and he was made its president in January 1823 at the age of 37. In character and background, Andrew Jackson presented a strong contrast to the Bank’s aristocratic president. Born in the Waxhaw settlement of South Carolina in 1767, orphaned during the American Revolution, poorly educated and described as a wild roughneck, Jackson had been “the most roaring, rollicking, game-cocking, horse-racing, card-playing, mischievous fellow” in his community. In 1788, he headed west to seek his fortune in Tennessee. He married a well-connected divorcee, Rachel Robards; served as a major general in the Tennessee militia and the U.S. Army; pulverized the British at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815—a victory that made him the most popular man in America—and lost a bid for the presidency in 1824. Although he received a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, there was no majority, and the election was thrown into the House. Disregarding explicit instructions from the A cartoon lampooning “King Andrew the First” appeared in the campaign of 1832. Kentucky legislature to back “the regional candidate,” Kentucky representatives followed Henry Clay’s lead in supporting per, Jackson carried himself with military stiffness, perhaps John Quincy Adams. The election was a turning point for Jackpartly attributable to the lead bullets he carried in his chest and son. His conviction that “Corruptions and intrigues at Washingleft arm—souvenirs of a gunfight and a duel in which one of ton ... defeated the will of the people” and cheated him of the Jackson’s opponents died. Jackson looked presidential, accordpresidency had a profound impact on the development of his ing to contemporary accounts, with his sharp jaw, steely blue democratic thinking. In 1828, he ran again for the presidency eyes and long bony nose. An astute and practiced politician, he and won hands down as the champion of democracy. was enamored of power and driven by personal ambition. Democracy, which he defined as majority rule, became the He also hated banks—or so he told Biddle at one of their central tenet of his political philosophy: “The people are soverfirst meetings. “I do not dislike your bank any more than all eign,” he insisted, “their will is absolute.” The people, acting banks,” he blithely admitted. Undoubtedly Jackson’s prejudice through the ballot box, must have the right to decide “upon all sprang from a number of factors: in 1795, involvement in a national or general subjects, as well as local.” In his first inauspeculative land scheme brought him a near brush with finangural address he stated his position simply: “The majority is to cial disaster and possible imprisonment; as a firm states’ rights govern.” advocate, he opposed strong central government and loose inSix feet tall, rail-thin and known to have a volcanic tem- CONSTITUTION/FALL 1990 61 ory” with the electorate. Secterpretations of the Constituretary of state under John tion; and like many westerners, Quincy Adams and six times he preferred gold and silver to elected Speaker of the House paper money and was decidedly of Representatives, he was a suspicious of the note-issuing, power in Congress. He could land-speculating, credit-producnot be dismissed or his wishes ing activities of banks. disregarded. “The friends of Since the Second Bank of the Bank,” he informed the United States would come Biddle, “expect the application up for recharter in 1836, Biddle to be made. The course of the visited the new President at the President, in the event of the White House in the hope of passage of the bill, seems to be gaining support from his ada matter of doubt and speculaministration. Jackson spoke to tion.” him bluntly: “I think it right to This was a false and selfbe perfectly frank with you,” he serving statement. Biddle had said, “I do not think that the been warned by several adpower of Congress ... to charter ministration officials that if he a Bank [extends beyond the challenged the President with District of Columbia.] I have a “trial of strength,” recharter read the opinion of John Marwould be vetoed. But Biddle shall ... and could not agree had little choice. Leaders of with him.” Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky denounced President Jackthe National Republican A month later, Jackson reson’s action, calling it “a perversion of the veto power.” party—such as Daniel Webvealed the extent of this disster and the former President, agreement. He referred to the John Quincy Adams—on whom Biddle relied for the Bank’s Bank in his first State of the Union message and claimed that “a support, wanted him to apply. They assured him that Congress large portion of our fellow citizens” questioned both the constiwould override a veto if Jackson dared to invoke it. They betutionality and expediency of creating a national bank, adding, lieved that the Bank was essential to the country’s economic “it must be admitted by all that [the Bank] has failed in the great stability and that the country knew it. A presidential veto, they end of establishing a uniform and sound currency.” believed, would bring about Jackson’s defeat in the fall elecWhich was utter nonsense. Since Biddle’s election as tion. president, the Bank had done an excellent job of regulating the So Biddle decided to proceed with the recharter request. nation’s currency and credit; the government’s deposits were Early in 1832, a bill was introduced into both houses of Consafe in its vaults. But Jackson suspected the Bank of using its gress. Immediately, the administration girded for battle. funds to support favored political figures. And in this, he was Two of the most notable enemies of the Bank were Attorright. The Bank did subsidize certain congressmen—Daniel ney General Roger B. Taney and Amos Kendall, the fourth Webster, for one. (“I believe my retainer has not been renewed auditor of the Treasury and a former journalist with a talent for or refreshed as usual,” the Massachusetts senator coyly reeditorial invective. Both men had Jackson’s ear and played on minded Biddle in 1833. “If it be wished that my relation to the his prejudices against banks. A member of the landed aristocBank should be continued, it may be well to send me the usual racy of southern Maryland whom Jackson would later appoint retainers.”) Jackson also believed that the Bank supported canChief Justice, Taney had virtually run the 1828 Democratic didates in political elections and generally acted in the interests campaign in Maryland. He had a towering legal intellect and the of the rich over the public at large. The Bank should be reined President valued his advice. The attorney general kept up a barin, he thought, and he demanded “certain modifications” in its rage of criticism of the Bank and graphically depicted the danoperations—though these were not spelled out. Had Biddle gers it posed to the liberty of the American people. “It is the made a genuine attempt at addressing these concerns, perhaps immense power of this gigantic machine,” he wrote, “— the Bank would have survived. Unfortunately, the entire quescontrolling the whole circulating medium of the countrytion of the Bank’s recharter got mixed up with politics. An old increasing or depressing the price of property at its pleasure all political enemy of Jackson, Kentucky senator Henry Clay, over the United States ... it is that power concentrated in the stepped into the picture and demanded of Biddle that he forhands of a few individuals—exercised in secret & ... constantly mally apply for a recharter in 1832, four years early. felt-irresponsible & above the control of the people or the govAudacious, charming and sharp-tongued, Clay was a skillernment for the 20 years of its charter, that is sufficient to ful orator and politician, and he had just been nominated for the awaken every man in the country if the danger is brought dispresidency by the National Republican Party to run against tinctly to his view.” Jackson in 1832. Clay desperately needed an issue that could In addition, Taney deplored the timing of the recharter redim, if not extinguish, the enormous popularity of “Old Hick- 62 quest: the Bank had dared to enter the political arena and injudged the Bank constitutional. volve itself in the electoral But he declared, “To this conprocess. “Now as I understand clusion I cannot assent.” He the application at the present discounted “mere precedent” time,” he wrote, “it means in as a congressional justification plain English this—the Bank for recharter, citing it as “a says to the President, your next dangerous source of authority.” election is at hand—if you Moving into more controcharter us, well—if not, beware versial areas, he argued that the of your power.” high court ought not to have The Jacksonians in Concontrol over the other two gress, under the leadership of branches of the government in men like Missouri senator the matter of constitutional Thomas Hart Benton, a big, interpretation. Each must “for powerful-looking man with an itself be guided by its own ego to match, and Congressopinion of the Constitution.” man James K. Polk of TennesEvery public officer who takes see, struggled unsuccessfully to an oath to uphold the Constitukill the recharter bill. The Sention, Jackson continued, ate passed it on June 11, 1832, swears to support it “as he by a vote of 28 to 20, and the understands it, and not as it is House followed a month later understood by others.” It was on July 3, voting 107 to 85. Jackson reacted in an ex- Attorney General Roger B. Taney, a political advisor to the as much the of the House, the plosion of anger when the bill President, urged Jackson to veto renewal of the Bank’s charter. Senate and the President to decide upon the constitutionalfinally reached his desk. He ity of any bill that might come must slay this “hydraheaded before them as it was of the “supreme judges,” he declared. monster,” as he called the Bank, not cage it as he originally thought. The Bank corrupted “our statesmen,” impaired “the Then he pronounced the words that were to shock future morals of our people” and, worst of all, threatened “our liberty,” generations: “The opinion of the judges has no more authority he ranted. It bought up “members of Congress by the Dozzen over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the [sic],” subverted the electoral process, aimed to “destroy our rejudges, and on that point the President is independent of both.” publican institutions” and stole from the poor working classes What Jackson argued here was the equality and independence to fatten the pockets of the rich. of each branch of the federal government. Nothing in the ConHe took a week to satisfy himself over his veto message. It stitution gives the Supreme Court the authority to pronounce detonated in Congress on July 10. It was a powerful polemic, final judgment on its meaning. A balance had been established one of the most important presidential vetoes in American hisby the Constitution among the three branches, and through that tory, and written to convince the electorate that the Bank should balance the liberty of the people was protected. To allow the be destroyed. The message began on a nationalistic note by Supreme Court total and final authority skewed the system. observing that almost a third of the Bank’s stock was held by “The authority of the Supreme Court,” he averred, “must not be foreigners-wealthy and titled foreigners especially. “By this permitted to control the Congress or the Executive when acting act,” lectured Jackson, “the American Republic proposes in their legislative capacities, but to have only such influence as virtually to make them a present of some millions of dollars.” If the force of their reasoning may deserve.” we must “sell monopolies,” he went on, “it is but justice and The notion that the Supreme Court had the right to detergood policy ... to confine our favors to our own fellow citizens, mine the final meaning of the Constitution remained alien to and let each ... benefit by our bounty.” Furthermore, Jackson’s thinking throughout his presidency. He believed that investigation revealed that relatively few people—“chiefly of that right belonged to the people. As a lawyer and a former the richest class”—owned stock in the Bank, and yet they dijudge of the Tennessee superior court, he would allow the vided profits from investments of government funds generated courts the right to review and interpret the law, but he absofrom taxes on all the people. Jackson also condemned the lutely denied them ultimate authority to pronounce “the true control of the institution, which rested in the hands of the meaning of a doubtful clause of the Constitution.” The Court’s wealthy. “It is easy to conceive,” he wrote, “that great evils to right to interpret law may be “endured,” he said, “because it is our country and its institutions might flow from such a concensubject to the control of the majority of the people.” But Jacktration of power in the hands of a few men irresponsible to the son thought that for the Court to have the last word was altopeople.” How can a nation be free, he asked, if the few control gether objectionable; it gave four persons “the right to bind” the the many? Then Jackson turned to the constitutional question. He acstates and the people with fetters that they could not break exknowledged that in the McCulloch case the Supreme Court had cept by the difficult, if not impossible, process of amending the CONSTITUTION/FALL 1990 63 Andrew Jackson (left, with cane) slays the many-headed monster, the Second Bank of the U.S. The cartoonist frames the President’s threat in elegant terms: “Biddle thou monster Avaunt!! … or by the Great Eternal I’ll cleave thee to the earth.” Constitution. That was not democracy, Jackson insisted. That was oligarchy—government by the few. Throughout his political life he maintained that such elitist rule had no place in the governing process of a free country. The fact that the Justices were appointed, not democratically elected, made the situation worse because their decisions could not be reviewed by the electorate, a process that would have given the decisions some semblance of popular consent. Should the three branches disagree on a constitutional issue, then, Jackson declared, the decision should revert to the people and be rendered through the ballot box. Jackson understood that without a rule of law interpreted by a high court, the minority had no way to protect itself against a willful and irresponsible majority. But he discounted this danger, truly (if naively) believing in the wisdom and goodness of the great mass of Americans to act responsibly. His political philosophy rested on the assumption that a “virtuous” people would “arrive at right conclusions” when dealing with fundamental human questions. In line with Jackson’s beliefs was his conviction that the relationship between government and the citizenry must be as 64 direct as possible. He suggested the direct election of most public officials and the regular “rotation” of those appointed to office, and he supported direct election of senators (a measure that was put into effect in 1913 with the ratification of the 17th Amendment). “Every officer should in his turn pass before the people, for their approval or rejection,” he insisted. Jackson even advocated popular election of federal judges, commenting: “... the judges should not be independent of the people, but be appointed for not more than seven years. The people would always re-elect the good judges.” He also tried unsuccessfully to abolish the Electoral College—a reform that many advocate today—and to limit the President’s tenure to one term. Jackson concluded his veto message with what sounded to some like an invocation of class warfare: “It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes,” he exclaimed. “In the full enjoyment of ... the fruits of superior industry, economy and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to ... make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers—who have neither the time nor the virtue of his veto power, exmeans of securing like favors pects to force his will upon to themselves, have a right to Congress. That was “hardly complain of the injustice of reconcilable with the genius of their Government. ... If it representative Government,” would confine itself to equal Clay thundered. It was downprotection, and ... shower its right revolutionary. favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, Despite heroic efforts to it would be an unqualified reverse Jackson’s action, the blessing. In the act before me opposition could not convince there seems to be a wide and Congress to override the veto. unnecessary departure from Nor could they convince the these just principles.” country of the necessity to do Biddle reacted to the veto so. In writing the veto as he did, with outrage. He likened it to Jackson laid the Bank issue “the fury of a chained panther, squarely before the public, in biting the bars of his cage.” It effect asking them whether they was a “manifesto of anarchy,” thought the country could surhe told Henry Clay, “such as vive as a free nation if private, Marat or Robespierre might unaccountable concentrations of have issued to the mob” durwealth were more powerful ing the French Revolution. than a democratically elected The opposition in the Daniel Webster, who made an impassioned Senate speech government. The alternatives Senate, led by Clay and Daniel charging that Jackson’s veto was “a claim to despotic power.” were clear. Either Clay and the Webster, thundered its denunBank—or Jackson and no Bank. ciations of Jackson’s “outraAnd in the election held the geous and unconstitutional” arguments. Crowds jammed the following fall, Clay was overwhelmingly defeated. Senate gallery to hear the “god-like Daniel,” who was contempThe government’s deposits were subsequently removed tuous of the veto, outraged by its attitude toward the Supreme from the Bank, and the institution died a slow and agonizing Court and downright furious about what he saw as the Presideath. When its national charter expired in 1836, it secured a dent’s attempt to divest Congress of its full legislative authority. state charter as the Bank of the United States of Pennsylvania Webster lifted his voice and let it drop dramatically, his great but sank into bankruptcy and closed its doors in 1841. Jackson head rolling to the rhythm of his cadences. “According to the had won the Bank War, but at some cost. The government funds doctrines put forth by the President,” he growled, “although were deposited in state banks, which, no longer restrained by a Congress may have passed a law, and although the Supreme prudent national Bank, freely lent money and created a boom in Court may have pronounced it constitutional, yet it is, neverland speculation. To stem it, Jackson declared paper money theless, no law at all, if he, in his good pleasure, sees fit to deny worthless for the purchase of public lands, demanding payment it effect; in other words, to repeal or annul it.” Webster continin gold and silver. Credit collapsed, and the country was swept ued: “Sir, no President and no public man ever before advanced up into the Panic of 1837, a depression that swamped Europe as such doctrines in the face of the nation. There never was a mowell as the United States. Jackson’s critics claimed that his fiment in which any President would have been tolerated in asnancial program had created economic chaos. serting such a claim to despotic power.” The nation had arrived Still, Jackson had strengthened the hand of the President by at a “new epoch,” he warned. “We are entering on experiments his innovative use of the veto. In 40 years, only ten acts of Conwith the government and the Constitution, hitherto untried, and gress had been struck down by a executive. (Jackson employed of fearful and appalling aspect.” the veto a total of twelve times during his tenure.) In every inHenry Clay agreed and rose to speak. He called the Presistance, Presidents had claimed that the offending legislation dent’s action “a perversion of the veto power.” The framers of violated the Constitution. It had been therefore generally acthe Constitution never intended it for “ordinary cases,” he cepted the question of a bill’s constitutionality was the only claimed. “It was designed for instances of precipitate legislareason to apply a veto. Jackson disagreed. He believed that a tion, in unguarded moments.” It was to be used rarely, if ever; President could strike down a bill for any reason whatever when something all previous Presidents had understood. Neverthehe felt it harmful to the people and the nation. He therefore esless, Jackson had already used the veto four times in three sentially altered the relationship between the legislative and years. “We now hear quite frequently, in the progress of measexecutive branches of government. The President now had a ures through Congress,” Clay continued, “the statement that the distinct edge. He was becoming head of government, not simply President will veto them, urged as an objection to their pasan equal partner. sage!” What a monstrous threat, he snorted. The President, by But Jackson ultimately lost the larger question of who has CONSTITUTION/FALL 1990 65 Cartoonist Edward Clay’s view of the effects of the Panic of 1837: workers are idle; only pawnbrokers and grog shops thrive. the final say as to the meaning of the Constitution. Today, five Supreme Court Justices have the authority to dictate whether or not the American people have the right for example, to legalize abortion, outlaw capital punishment or segregate schools under their fundamental law. Indeed, five people ultimately govern what actions Americans may take on virtually every social, economic and political question confronting them. Jackson’s 66 ideals of democracy, touching each branch of government, have not yet been—and perhaps never will be—fully attained. Robert V. Remini, Professor of History at the University of Illinois is the author of a three-volume life of Andrew Jackson. He has just completed a biography of Henry Clay, to be published in 1991.