Literature Review on Recovery: Developing a Recovery Oriented

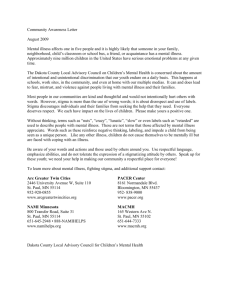

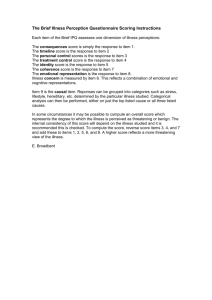

advertisement