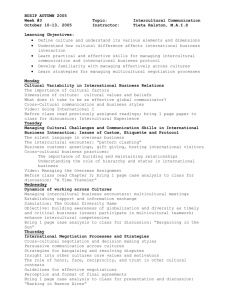

Intercultural Simulation Games for Management Education in Japan

advertisement