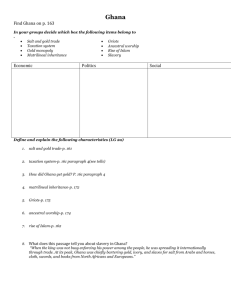

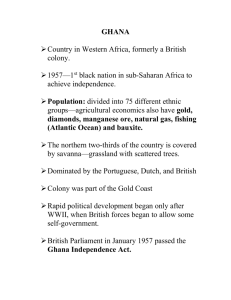

State-Business Relations and Economic Performance in Ghana

advertisement