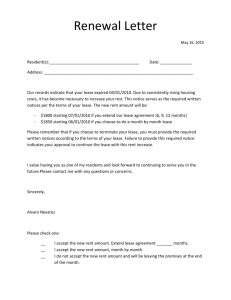

[1981] 1 All ER 161

advertisement

![[1981] 1 All ER 161](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008777200_1-4780d7b7e46c733f72d12edf6a4ae943-768x994.png)