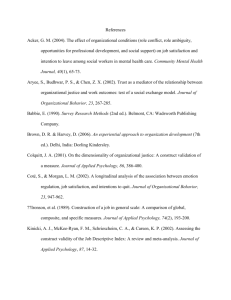

Assessing the Construct Validity of the Job Descriptive Index: A

advertisement