New Mexico

Indian Affairs Department

January 2009

Welcome to the 2009 Legislative Session!

MESSAGE FROM CABINET

SECRETARY ALVIN WARREN

As we embark on the 2009 New Mexico Legislative Session we have chosen to use

this edition of I-News to reflect on the complex

history that has brought us to this point in statetribal relations as well as to look forward at the

opportunities to build on the progress that has

been made.

I - N ew s

The interview with former Cochiti Governor Regis Pecos, Chief of Staff to Speaker of

the House of Representatives Ben Lujan and the

article by Mr. Bernie Teba, Tribal Liaison at the

Children, Youth and Families Department, provide rare and valuable insights into the series of

legal and political milestones that have defined

the present relationship between the State of

New Mexico and the 22 sovereign Indian nations, tribes and pueblos. At each turn there

have been a number of visionary and courageous leaders who sought to move away from

conflict and create agreements and systems that

would foster greater collaboration between the

state and tribal governments.

Tribal sovereignty and self-determination

The inherent sovereignty of Indian

tribes is recognized in the U.S. Constitution and

further reinforced by numerous treaties, federal

legislation and court decisions. Particularly

since the 1970’s, with the shift in federal Indian

policy to one of tribal self-determination, tribal

governments have increasingly exercised their

powers of self-governance and developed institutions to protect and promote their interests.

For example, federal laws such as the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act reaffirmed tribal self-determination

and self-governance and resonated with the fundamental American belief that local problems

are best solved at the local level.

Cont. on p. 6

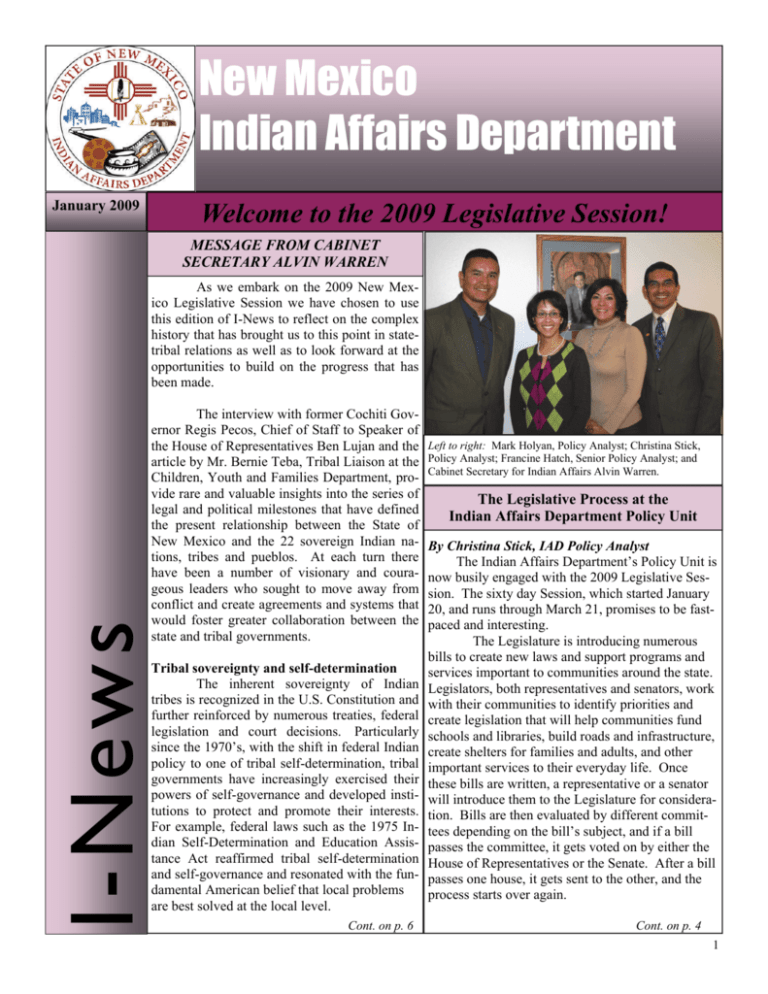

Left to right: Mark Holyan, Policy Analyst; Christina Stick,

Policy Analyst; Francine Hatch, Senior Policy Analyst; and

Cabinet Secretary for Indian Affairs Alvin Warren.

The Legislative Process at the

Indian Affairs Department Policy Unit

By Christina Stick, IAD Policy Analyst

The Indian Affairs Department’s Policy Unit is

now busily engaged with the 2009 Legislative Session. The sixty day Session, which started January

20, and runs through March 21, promises to be fastpaced and interesting.

The Legislature is introducing numerous

bills to create new laws and support programs and

services important to communities around the state.

Legislators, both representatives and senators, work

with their communities to identify priorities and

create legislation that will help communities fund

schools and libraries, build roads and infrastructure,

create shelters for families and adults, and other

important services to their everyday life. Once

these bills are written, a representative or a senator

will introduce them to the Legislature for consideration. Bills are then evaluated by different committees depending on the bill’s subject, and if a bill

passes the committee, it gets voted on by either the

House of Representatives or the Senate. After a bill

passes one house, it gets sent to the other, and the

process starts over again.

Cont. on p. 4

1

I - N ew s

The State-Tribal Collaboration Act

legislature. It is important to note that the bill does not

give tribes a right or review of agency action.

As the state and the tribes share a range of comThe proposed State-Tribal Collaboration Act

(“Act”) represents the shared interests and combined effort mon interests, the formalization of tribal collaboration poliof both state and tribal government in recognizing the im- cies by all cabinet-level state agencies will improve cooperation and communication between the state and tribal

portance of maintaining respectful and open communicagovernments to address these shared issues. This Act,

tion and cooperation on issues of mutual interest or concern. The Act builds on Governor Richardson’s Statement which will be introduced by Senator John Pinto, is among

Governor Richardson’s priority bills, has been endorsed by

of Policy and Process and Executive Order 2005-004,

which were the first steps in institutionalizing formal gov- the New Mexico Interim Indian Affairs Committee and has

the support of the All-Indian Pueblo Council, the Navajo

ernment-to-government relationships. Since then, tribal

Nation, the Mescalero Apache Tribe, several individual

consultation has proven effective in developing state

agency capacity and has led to increasing mutually benefi- Pueblos, the New Mexico Indian Affairs Commission, the

Albuquerque Indian Center and many others.

cial intergovernmental relationships. The purpose of the

Act is to provide for greater consistency across all cabinetlevel agencies and to ensure that effective government-toSenate Indian and Cultural Affairs Committee

government collaboration and communication continues in

future administrations.

Sen. John Pinto, Chairman (505-986-4835)

Sen. Eric G. Griego, Vice-Chairman (505-986-4862),

The Act also provides for an Annual Summit between the Governor and all twenty-two tribal leaders which egriego@yahoo.com

Timothy Z. Jennings (505-986-4733)

will promote true government-to-government dialogue on Sen.

Sen. Lynda M. Lovejoy (505-986-4310), lynda.lovejoy@nmlegis.gov

issues of mutual interest. In addition, the Act will ensure

Sen. Cisco McSorley (505-986-4485), cisco.mcsorley@nmlegis.gov

that all cabinet-level agencies create, with the Indian AfSen. William H. Payne (505-986-4703), william.payne@nmlegis.gov

fairs Department’s (“IAD”) assistance, policies for promot- Sen. Stuart Ingle (505-986-4702), stuart.ingle@nmlegis.gov

ing effective communication, collaboration and positive

government-to government relations between that state

agency and tribal governments. These agencies will also

2009 marks the 40th Anniversary of the American

be required to designate a tribal liaison who reports directly

Indian Graduate Center (AIGC). If you are an

to the office of the secretary and who will assist the agency

with complying with the Act. Currently, eighteen cabinet- AIGC alumna or alumnus or know one, please

visit www.aigcs.org and click on AIGC Alumni

level state agencies have adopted tribal consultation policies and sixty tribal liaisons or agency contacts have been Connection and update your information.

Information can also be updated by calling

designated in twenty-eight such agencies.

Additionally, the Act requires that all state agency (505) 881-4584.

managers and employees who have ongoing communication with tribes complete a training, provided by the State

Personnel Office in collaboration with IAD, on promoting

"40th Anniversary

effective communication and collaboration between the

Kick-Off Event"

state agencies and tribes, the development of positive stateSaturday, February 7, 2009,

tribal government-to-government relations, and cultural

5:30pm

competency in providing effective services to American

Albuquerque The Magazine

Indians or Alaska Natives.

Finally, each agency will be required to submit an

550 Merchantile Avenue, NE,

annual report to IAD on the agency’s implementation of

Top Floor

the Act and their programs and services that directly affect

Space is limited so please

American Indians and Alaska Natives. IAD will be reRSVP at www.aigcs.org

sponsible for compiling these into an annual report that

will be submitted to the Governor’s Office and the state

By Francine Hatch, IAD Senior Policy Analyst

2

I - N ew s

Historic “State-Tribal Collaboration Act” Introduced in New Mexico Senate on January 22

dorsed the bill and there is strong support from the AllIndian Pueblo Council, the Navajo Nation, the Mescalero

Apache Tribe, several individual Pueblos as well as the

New Mexico Commission on Indian Affairs, the Bernalillo

County Off-Reservation Indian Health Commission and the

Albuquerque Indian Center.

As stated by Isleta Pueblo Governor Robert

Benavides, “This Act will improve direct tribal communication with the Governor through an annual summit with

tribal leaders, and will further develop tribal communication and collaboration policies by state agencies. The State

Tribal Collaboration will enhance reporting on Native

American programs administered by the state, and will

support the continuation of state agency tribal liaisons in

their vital role.”

“Strengthening and expanding collaboration between the state and tribal governments through SB 196 will

result in better coordination of resources to address shared

priorities as well as higher quality services to our more

The State-Tribal Collaboration Act was introduced than 200,000 Native American citizens,” said Indian Affairs Secretary Alvin Warren. “The ‘State-Tribal CollaboJanuary 22, 2009, on the Senate floor by Senator John

Pinto. Senate Bill 196 would create a statute for effective ration Act’ promises to set another significant milestone in

government-to-government communication and collabora- our shared state and tribal endeavor to foster positive government-to-government relations that will benefit all New

tion between the state and tribal governments.

Mexicans.”

“Since taking office, I have made it a priority to

Contact: Rima Krisst, Indian Affairs PIO, 505-795-5049

strengthen the relationship between the State of New Mexico and our sovereign tribes,” said Governor Richardson.

“The State-Tribal Collaboration Act will further my commitment to Native Americans and provide greater consisSAVE THE DATE!

tency across all cabinet-level agencies in working with the

PLEASE JOIN US FOR

twenty-two tribes, nations, and pueblos in New Mexico,

and will ensure productive government-to-government relationships continue into the future.”

Senator John Pinto and New Mexico Cabinet Secretary for

Indian Affairs Alvin Warren at the State Capitol .

Barbara Smith.photo

INDIAN DAY

“SB 196 will require cabinet-level agencies to develop policies that promote communication and collaboration between the state and tribal governments. Training

would also be provided to state employees so they can

work effectively to address Native American issues,” said

Senator Pinto. “This is a very meaningful and exciting legislative proposal and something we’ve worked toward for a

long, long time. I am honored to sponsor this landmark

bill.”

FEBRUARY 6, 2009

8:30 A.M. TO 12 NOON

AT THE NEW MEXICO

STATE CAPITOL ROTUNDA

EVERYONE IS WELCOME!

The Interim Indian Affairs Committee has en3

I - N ew s

The Legislative Process at the Indian Affairs

Department Policy Unit

cont. from p.1

This process can sometimes be long and difficult to

navigate, so the IAD Policy Unit works to help make it all

more accessible and easier to understand for our Tribal and

off-reservation Native American communities. During the

session, IAD will provide regular updates on all Indianrelated bills through email and our website. These updates

will include information about the bill that will be helpful

for understanding what the bill does and where it is in the

process of becoming law. Check out the IAD website for

this and other important information related to the Legislative Session.

Check out the IAD website at

www.iad.state.nm.us

for Bill Summaries and other

important updates!

The IAD Policy Unit will also be busy in providing

analysis of all Indian-related legislation to the legislature.

During the session, IAD will receive requests from the

Legislative Finance Committee (“LFC”), an important

committee of the Legislature, requesting analysis of a particular bill. These analyses, called a Fiscal Impact Reports

(“FIR”), are the bulk of what the Policy Unit will do during

the session. It is the Policy Unit’s job to provide accurate

and detailed analyses of a bill in the FIR, describing how a

bill will benefit or not benefit tribes, Native Americans,

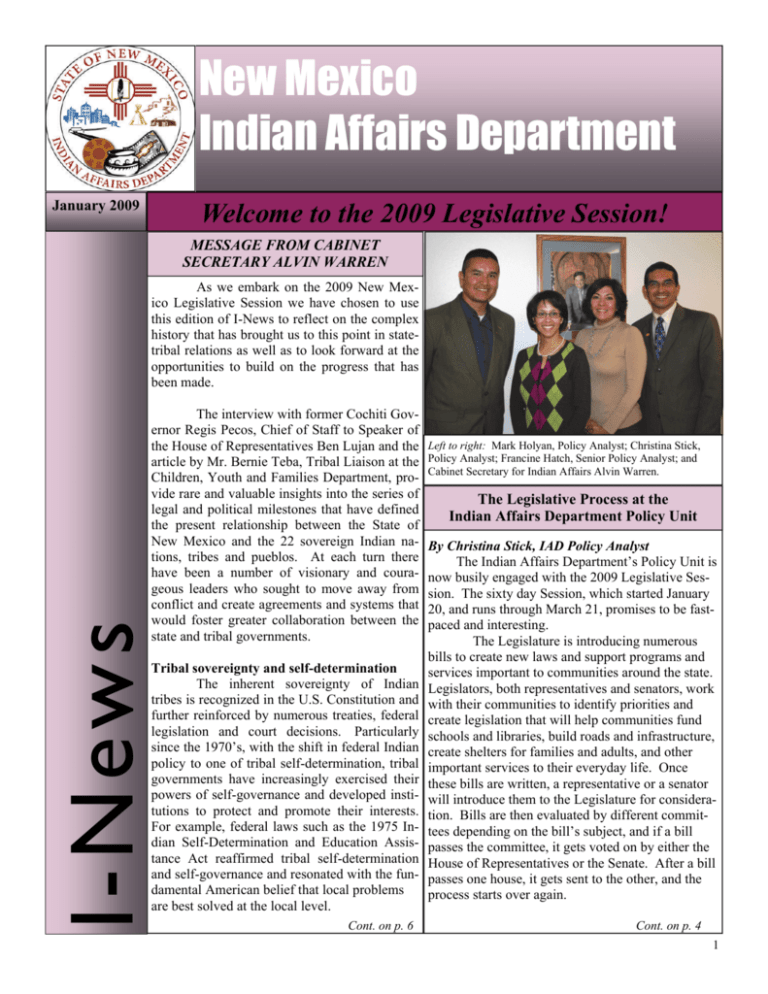

and Native American organizations in this state. The Policy Governor Bill Richardson gives his State-of-the-State address to a full

Unit tries to provide balanced and fair analyses while still House on January 20, kicking off the 2009 Session! Rima Krisst photo

helping legislators understand the important and great

needs for infrastructure and services in Tribal and offreservation communities.

2009 Legislative Session Important Dates:

The Policy Unit has 24 hours to complete an FIR

Jan. 30, 2009: Deadline for capital

for the LFC, after which the LFC will take our analysis and

outlay reauthorizations

combine it with other agencies’ to create a “Public

Feb. 6, 2009: Indian Day at the

FIR.” This Public FIR will be posted to the Legislative

Legislature!

website and it is free and available to the public. Check out

Feb. 19, 2009: Deadline for introduction of

the New Mexico Legislative Website to find the Public

bills and capital outlay requests

FIRs for all bills introduced during the session and other

March 21, 2009: Session Ends (noon)

important information about the Legislative Session.

Check out the NM Legislative

website at

www.nmlegis.gov/lcs!

April 10, 2009: Bills not acted upon by Governor are pocket vetoed

June 19, 2009: Effective date if bills not carrying an emergency clause or other specified

date

4

I - N ew s

The Amendments to the New Mexico Subdivisions Act Legislation

Often Indian tribes, nations and pueblos have information regarding these important public values, particularly when the proposed development is near tribal boundaries or in areas sensitive to them. In some instances, a tribe

may become aware of subdivision developments so late in

the planning and implementation process that they are left

to resort to litigation to ensure protection of public values

not identified earlier in the plat approval process. Because

subdivisions can similarly have a profound impact on tribal

communities regarding water quality and quantity, transportation, erosion, and cultural properties such as archeological sites and unmarked burials, it would further “open

government” for New Mexico tribes to receive adequate

and timely notice in the early stages of preliminary plat

approval.

Based on feedback from tribal leaders, boards of

county commissioners and other stakeholders, IAD recognized a need for all participants to continue to be proactive

participants in this process as well. HB 37 would further

this goal by requiring counties to notify tribes of newly

proposed or merged subdivision developments. The underlying purpose would be to prevent or mitigate delays or

conflicts for any newly proposed or merged subdivision

among tribes, counties, and developers.

It is important to note that the amendments proposed in HB 37 would not allow tribes to halt proposed

subdivisions nor would they change any requirements for

developers when providing documentation to support a

newly proposed or merged subdivision. They also would

not change any duties of the County when considering

whether to approve a subdivision’s preliminary plat. HB

37 would simply include tribes in that list of agencies that

would be called upon to provide an opinion on the human

and environmental impact of a newly proposed or merged

subdivision as part of the county’s decisionmaking process.

Indeed, some county regulations and/or practices

already include tribes as among those agencies from whom

a request may be made. The amendments in HB 37 are

therefore aligned with the existing trend for the regulatory

procedures of some counties. HB 37 will standardize this

practice by all Boards of County Commissioners. HB 37

has been endorsed by the New Mexico

House Health & Government Affairs Committee

Interim Indian Affairs Committee and

Rep. Mimi Stewart

Chair

986-4840 mstewart@osogrande.com

has the support of the All-Indian Pueblo

Rep. Jeff Steinborn

Vice Chair 986-4248 jeff.steinborn@nmlegis.gov

Council, the Mescalero Apache Tribe,

Rep. Eleanor Chavez

Member 986-4235 eleanorchavez@gmail.com

several individual Pueblos, the New

Rep. John A. Heaton

Member 986-4432 jheaton@caverns.com

Rep. Dennis J. Kintigh

Member 986-4453 askdennis@dennisknight.com

Mexico Indian Affairs Commission, the

Rep. Luciano "Lucky" Varela Member 986-4318

County of Santa Fe, the New Mexico

Rep. Gloria C. Vaughn

Member 986-4453

Association of Counties, and many

Rep. Jeannette O. Wallace Member 986-4452 wallwace@losalamos.com

others.

By Mark Holyan, Policy Analyst

The Indian Affairs Department (“IAD”) has been

working steadily over the past year to develop new legislation and legislative amendments for this year’s legislative

session. In addition to the new State-Tribal Collaboration

Act, IAD is proposing amendments to the New Mexico

Subdivision Act. The current Subdivision Act provides for

the regulation of county subdivision development, and governs the requirements for developers and counties for approving subdivision plans, or plats, as they are

known. These regulations provide for responsible development that protects human and environmental interests for

everyone as new subdivisions are planned and built.

During the tenure of Governor Richardson’s administration much progress has been made to further the

government-to-government relationship between the State

and the 22 tribes of New Mexico. Related to this process,

but at a separate level of government, is the Subdivision

Act Amendments (“Amendments”). HB 37, sponsored by

Representative Ray Begaye and endorsed by the Interim

Indian Affairs Committee, would amend the New Mexico

Subdivisions Act to include tribes in the list of agencies

notified by Boards of County Commissioners about proposed new or merged subdivisions.

Currently, county commissioners are required to

request opinions from the Office of the State Engineer, the

Department of the Environment, the Department of Transportation, the Soil and Water Conservation District and

such other public agencies as a county deems necessary,

when considering whether to approve a preliminary plat

design. The approval process is meant to ensure that a developer’s preliminary plats have reasonably demonstrated

that each subdivision will have:

• water of sufficient quantity and quality for the

• community,

• adequate solid and wastewater removal,

• satisfactory roads,

• soil conservation to prevent flooding and erosion,

and

• protection of cultural properties and antiquities such

as burials and unmarked graves.

5

I - N ew s

MESSAGE FROM CABINET SECRETARY ALVIN WARREN

Cont. from p. 1

New Mexico has 22 federally-recognized tribes,

nations and pueblos and over 205,000 Native American

citizens who comprise nearly 11% of our state’s population. As is true for many other states, state-tribal relations

in New Mexico were historically characterized by mutual

indifference or conflict over issues such as jurisdiction,

natural resources and access to funding. As described in

the interview with former Governor Pecos, the establishment of the Commission on Indian Affairs in 1953 and the

subsequent creation of the Office of Indian Affairs marked

the beginning of new approach to state-tribal relations.

This was further strengthened in the 1980’s and

1990’s. As tribes expanded their capacity to exercise selfgovernance and the visibility of tribal governments increased, the interactions between the state and the tribes

increasingly were seen as intergovernmental. This coincided with a trend toward “devolution” of certain federal

programs to the state level, which compelled state and

tribal governments to improve communication in order to

ensure funding and services met the needs of a shared Indian constituency. Farsighted tribal and state leaders came

to recognize that states and tribes have numerous shared

interests and responsibilities, including allocating public

resources effectively and efficiently; providing basic services such as health care, education, and law enforcement

to their shared citizens; and protecting the environment

while striving to develop strong and diversified economies

and sustaining a skilled workforce. New institutions were

needed to support greater cooperation between fellow governments.

A New Era in State-Tribal Relations

Governor Bill Richardson and Lt. Governor Diane

Denish recognized this need and were committed to building on the initial efforts of several previous governors, beginning with former Governor Toney Anaya. They knew

that it is vital to the well-being and prosperity of the State

of New Mexico to foster long-lasting and committed relationships with the tribes and to explore opportunities for all

parties to pursue collaborative programs and policies.

Accordingly, Governor Richardson moved quickly

in 2003 to elevate the Office of Indian Affairs to the only

Cabinet-level Indian Affairs Department in the United

States. Next, also in 2003, he signed an historic Statement

of Policy and Process with 21 tribes, nations and pueblos,

committing the Executive Branch to: recognize and re-

spect the sovereignty of each tribe; promote governmentgovernment relationships based on mutual respect; value

open communication and cooperation on issues of shared

interest or concern; and, encourage an open-door policy for

tribes to have their views seriously considered in the formulation and execution of state policy. To more fully implement the Statement of Policy and Process, Governor

Richardson issued Executive Order 2005-004 directing

statewide adoption of Pilot Tribal Consultation Plans by 17

state executive agencies. He also signed Executive Order

2005-003 that directed the creation of a statewide consultation policy on the protection of Native American sacred

places and repatriation.

From a holistic viewpoint, these interwoven policies have proven effective in developing state agency capacity and have led to increasingly beneficial relationships

between state and tribal governments. Direct outcomes of

Governor Richardson’s tribal policy initiatives include:

• 18 state agencies have adopted tribal consultation

protocols and policies;

• 60 tribal liaisons or agency contacts are currently

designated in 28 state agencies;

• 142 Native Americans have been appointed to influential state boards and commissions;

• State funding to tribes has increased significantly.

For instance, since 2003, approximately $124 million in capital outlay funding has been appropriated through IAD for tribal infrastructure projects,

with additional amounts flowing to tribes through

other agencies;

• The Department of Health has created an Office of

Native American Health and an American Indian

Health Advisory Council, which report on Indian

health disparities annually;

• A Native American Subcommittee and five Native

American Local Collaboratives emphasize tribal

needs as part of the state’s redesigned Behavioral

Health system;

• The state has entered into three water rights settlements with 7 tribes and created a fund to pay the

state's share of implementation costs; and,

• In economic development, the state has entered

into gross-receipts tax-sharing agreements with 9

tribes, and tribal governments and corporations

have begun to benefit from the state’s Certified

Communities Initiative and Job Training Incentive

Program.

6

I - N ew s

MESSAGE FROM CABINET SECRETARY ALVIN WARREN

It is important to also note that these achievements •

couldn’t have happened without the tireless advocacy and

support of tribal leadership, New Mexico legislators, and

the Indian Affairs Commission.

generating annual reports on each agency’s implementation of the Act as well as their programs and services that directly affect American Indians and Alaska

Natives.

In 2001 the State of Oregon found itself with an

opportunity similar to what is before us now in New

Mexico. Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber, in 1996, had

adopted Executive Order 96-30 to foster positive statetribal relations, similar to Governor Richardson’s Executive Order 2005-004. Oregon’s state and tribal leadership

similarly recognized the value of the institutions, agreements and interactions that had been secured pursuant to

the Executive Order. Oregon’s Legislative Commission on

Indian Services and Governor Kitzhaber knew the time had

come to codify these structures so they could continue to

benefit Oregon’s citizens into the future. As a result, SB

770 was enacted by the Oregon Legislature on May 11,

2001, and signed into law by Governor Kitzhaber on May

24, 2001. The eight years since enactment of this law have

proven the benefit of creating a statutory structure for

Governor Richardson’s proposed landmark “State- strong state-tribal collaboration and communication.

Tribal Collaboration Act,” endorsed by the Legislature’s

Interim Indian Affairs Committee, seeks to accomplish

In reflecting on the efforts here in New Mexico of

this, by:

so many over the past decades to move past conflict to define a new state-tribal partnership, I am inspired by the op• Providing for an annual summit between the governor portunity that now stands within our grasp. Especially in

and the 22 tribal leaders to address issues of mutual con- these challenging economic times, strengthening and excern, similar to what currently occurs in Arizona, Colo- panding collaboration between the state and tribal governrado, Washington and other states with significant Indian ments will result in better coordination of resources to address shared priorities as well as higher quality services to

populations;

our more than 200,000 Native American citizens.

The State-Tribal Collaboration Act: An Enduring

Framework for State-Tribal Collaboration and

Communication

In the year I have served in this position, I have

spoken about state-tribal relations with Governor Richardson and Lt. Governor Denish, all 22 tribal governors and

presidents, numerous legislators and many of my fellow

cabinet secretaries. I have heard a consistent theme. Many

recognize the benefit of the government-to-government

structures that have been put in place that have led to more

effective dialogue and cooperation between state and tribal

agencies. It is now time to further strengthen and codify

these structures to provide for greater consistency across all

cabinet-level agencies and to ensure that this effective

structure continues in future administrations.

•

ensuring the remaining 16 cabinet level agencies adopt

The “State-Tribal Collaboration Act” promises to

tribal communication and collaboration policies that

set

another

significant milestone in our shared state and

have proven beneficial to the 18 such agencies that curtribal

endeavor

to foster positive government-torently possess them;

government relations that will benefit all New Mexicans. I

sincerely appreciate your support for this landmark bill.

• ensuring the continued assistance of tribal liaisons in

all the cabinet-level agencies, including the six that currently have not yet designated such individuals;

Respectfully,

•

guaranteeing long-overdue training to state agency

managers and key employees so they may have the greatest

chance for success in working with tribal governments and

addressing the needs of Indian constituents; and

Cabinet Secretary Alvin Warren

7

I - N ew s

A Conversation with Regis Pecos, Part 1:

The Emergence of Federal Self-Determination Policy and its Impact in Defining State-Tribal Relations

Regis Pecos is the Chief of

Staff for House Speaker

Ben Lujan, former Director of the Office of Indian

Affairs, and former Governor of Cochiti Pueblo.

We asked Mr. Pecos to reflect on the movement toward tribal selfdetermination, including

the impact of the hallmark

Indian Self-Determination

and Education Assistance

Act of 1975, the effect that

the federal policy of

Indian self-determination

ultimately has had on

Regis Pecos

tribal-state governmentto-government relationships, as well as examples of incentives that emerged for tribes and states to communicate,

collaborate, and cooperate in the era of Federal

“devolution.”

Rima Krisst

REGIS PECOS:

In order to fully appreciate this time that history

will define as the era of “self-determination,” it is necessary to reflect upon the past to appreciate the evolution of

the events and relationships that shaped and formed this

period. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in

1847, officially beginning the occupation of the United

States. An important part of the treaty which annexed territory formerly part of Mexico was the recognition of

Pueblo land grants as acknowledged by Spain and Mexico.

The treaty with the Jicarillas was signed in 1851, establishing their present homelands. Referred to as the “Longest

Walk,” the Navajo experienced the forced removal and

imprisonment in the Bosque Redondo in 1864. The U.S.

Cavalry captured and imprisoned Geronimo and his band

in 1886. Then New Mexico joined the union in 1912.

In this period of 160 plus years since the signing of

the Treaty before New Mexico became part of the United

States, our 22 Indian sovereign nations had suffered immensely as the a result of the early extermination policies

at the hands of the United States and were now confined to

our reservations. Boarding schools like the Santa Fe Indian

School had been established beginning in 1890, and children some as young as 5 years old were taken from their

parents to begin the forced assimilation process through

education. Policies to prohibit the speaking of our Mother

tongue were strictly enforced. The government had established the Religious Crimes Code to prohibit the practice of

our way of life that would continue through the 1920’s.

But through it all, the Indian people and their leaders epitomized a spirit of extraordinary and profound resiliency to

survive, with the last of their homelands, reservations as

known to us today, their languages, although in a very fragile state to this day, families and communities weakened

and traumatized but revitalized, their traditional governments modified with adaptations as a result of the impositions of various governments, and a way of life reflecting

their core values since the time of creation.

I use that short history as a back-drop because it

sets the context within which our leaders would work from.

The many challenges that we face today; protecting our

only remaining homelands, our languages now in a fragile

state, our culture, our places of worship, our governance

systems and our sovereignty are the result of all of these

past intersections and impositions that define our values

and attitudes that are many times not so well understood.

The following is a classic example. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo recognized Pueblo land grants and important

water rights connected to those lands. Yet, in 1920, eight

years after New Mexico became part of the United States,

there was an effort to continue to reduce Indian land holdings in the name of resolving some long-standing disputes

over land and water rights ownership. It was an effort to

accommodate the railroad and those who wanted additional

lands. In this typical governmental approach, there would

continue the dual strategy of overpowering the Pueblos

specifically in the “famous or infamous” legislation

launched to accomplish this, known as the Bursum Bill. At

that time, the leaders of the All Indian Pueblo Council, in

their congressional testimony, referred to the threat of the

loss of lands as a threat to their very way of life. The Bureau of Indian Affairs joined the effort against the Pueblos

with their forceful policies, prohibiting the Pueblos’ right

to practice their religions. They implemented some harsh

policies to persecute those who did. The government has

always understood the intricate connections between land

and religion. All of this caused an uproar. The artists from

Taos and Santa Fe and others joined the fight that gave

birth to the modern day organization of the Southwest Association of Indian Affairs, known then as the New Mexico

Association of Indian Affairs. The effort launched a new

way of fighting policies at the federal level utilizing a

broad network of alliances. This effort on the part of many

resulted in the defeat of the Bursum Bill, which was a major proposal backed heavily by major political figures of

8

the time.

I - N ew s

A Conversation with Regis Pecos, Part 1:

The Emergence of Federal Self-Determination Policy and its Impact in Defining State-Tribal Relations

In the 1930s, the federal government’s policy was

to force reorganization of traditional governments in an

effort to democratize them by imposing an electoral process, a three branch government, and a constitutional framework. This was known as the Indian Reorganization Act.

The 1930s was also a time of a short-lived policy of returning children to their communities when Day Schools were

built in our communities. There were efforts to implement

programs for community development and programs to

preserve the art and culture of Indian people. This was, in

some ways, a first attempt of the federal government moving toward rebuilding what their policies had consciously

destroyed.

All of this came to light in a report named the

Meriam Report, which exposed the dire conditions Indian

people had been reduced to as a result of federal policies.

It was in this period that the federal government also began

shifting its responsibility for the education of Indian children to the states. The John O’Malley Act was the means

to accomplish this. This was their version of integrating

Indian children into public schools after their segregation

of children in boarding schools to assimilate them failed.

The end result today is that 90 percent of all Indian children go to public schools. The impact of this forced integration would have lasting impacts. Children were harshly

discriminated against because of their lack of proficiency

in English. For many the experience would result in conscious decisions not to teach their children our Mother

tongue after such devastating experiences in public

schools.

With the depression and the World Wars in the

40s, the pendulum moved back in the other direction, and

Indians became a drain on the federal budget. The ensuing

diminished support would result in yet another swing in the

extreme. This would follow, ironically, after our Indian

men and women gave their lives serving this country in the

wars. In the 1940s, many Indian men and women joined

the military to come to the aid of our country, despite the

fact that the government had subjected them to the worst

policies. Many served with distinction, including my own

father. The now famous Navajo Code Talkers epitomize

our men and women who gave their lives. But then, when

they returned and attempted to exercise their right to vote,

they were denied. Miguel Trujillo, a Pueblo man who

served in the military, used the legal system to challenge

this discrimination. In 1948, he prevailed and, with that

victory, the battle for Indian suffrage was finally won. Not

that long ago, right? But wars cost money and much like

with the wars’ cost today, domestic programs suffer. So, it

was then that the federal government began to implement a

whole new set of policies to rid itself of Indians in the

1950s.

It was at this time that the federal policies probably

reached its lowest point. The policy was to “terminate”

entire tribes, and concurrently Public Law 280 was aggressively being advanced to extend state jurisdiction over reservations. Also in effect was the policy of “relocation,” an

outgrowth of the federal governments’ initial effort to support Indian war veterans in finding employment and reintegrating them into society. The relocation policy led to the

beginning of what some refer to as the period of Indian

“self-termination,” which would have devastating longterm consequences.

The full effect of these devastating federal policies

caused the destruction and undermining of Indian people

and their communities from, once thriving independent,

self-sufficient, and self-governing bodies to communities

similar to those devastated by the wars that many of our

veterans had just returned from.

With termination policies in effect, the hope of

relocation, which had originally held great promise for a

better future for their children, became yet one more source

of division, created by the federal government that would

further put the survival of Indian communities at risk. Relocation years later would create a dichotomy of Indian

communities that would become divisive not unlike previous policies separating full bloods and half bloods and

categorizing them as civilized or uncivilized. The haunting

issues of blood quantum and “who is an Indian” would be

the ultimate consequence born out of that time.

The marketing scheme went like this – the sooner

you leave your language and culture behind, the sooner you

leave your families and communities behind, the sooner

you leave the reservation where there is no hope, the better

chance there will be that your children might have a better

life somewhere else. And so, those personally experiencing and living through the devastation, made the difficult

choice to move on and many never came home.

The reality today is that there are more urban Indians than there are reservation Indians, which poses major

policy considerations for the fair and equitable treatment

for reservation and off-reservation Indian citizens. Aside

from these policy considerations, we should remember that

we come from the same roots and are one family. Whatever we do, and wherever we live, we must bear in mind

not to perpetuate today the divisiveness that was caused by

federal policies by our treatment of one another along these

lines. Many live in urban America through no fault of their

own but as a result of circumstances and tough choices.

We have to constantly ask ourselves, “What are we9

I - N ew s

A Conversation with Regis Pecos, Part 1:

The Emergence of Federal Self-Determination Policy and its Impact in Defining State-Tribal Relations

doing differently in these times of self-determination, when

we are in control, than in those times when we weren’t, and

when we were critical of the federal government? We cannot be the victimizers as the federal government has been

throughout history.

As I attempt to answer the broad question of the

evolution of tribal/state/federal relations and the impact of

the self-determination policies on the relations, it is important to understand the immediate past and how personal

experiences drive our behaviors in these relationships.

Without this education, many in this process do not understand why we are so emotional and why we insist that this

history of our treatment as well as an understanding of our

responsibilities be part of any discussion. It is an awesome

responsibility we have to protect the last of our remaining

homelands and resources, our way of life that is defined as

religion by others, our language and culture, our places of

worship no longer part of our jurisdiction, our governance,

our sovereignty, our families and children.

Throughout history, the conceptualization of Indian policies has been driven by others and usually not for

our benefit. As long as we were not directly involved, even

the most thoughtful and well-intended considerations often

had unintended consequences. What could go wrong many

times did go wrong and we suffered through those times.

Crisis often times creates opportunities, however. By the

end of the 1950s, many were concerned that with this history of assaults on tribal languages and cultures, there were

imminent threats of their survival. In response to this, advocates, primarily non-Indian people, organized to create

the New Mexico Commission on Indian Affairs, and the

Office of Indian Affairs. It would be a response to protect

and preserve the languages and cultures of New Mexico’s

Indian tribes and pueblos. The Office and the Commission

would not evolve fully and expand until much later in the

1970s as a vehicle for tribal leaders to advocate their interests and guide tribal/state relations.

At the national level, there were many important

people in the 60’s, 70s and 80s that gave birth to a new

renaissance and rebirth. They created the foundation and

framework for what would be known as the selfdetermination era. This was driven as a result of their personal experiences. It also was the beginning of the formation of a new group of traditional leaders, and formally

educated Indian people, with a new set of experiences, all

working together in a complementary way. The move

from termination to self-determination was a dramatic and

drastic shift. How did it happen? There were many culminating factors and influences. The Civil Rights Movement

helped to energize the Indian rights movement. It was, in

many ways a wake-up call to America’s consciousness and

conscience. There are many on- and off-reservation Indian

leaders who contributed to this radical movement. They

saw this as necessary if were going to survive. They rose

to challenge the status quo as our forefathers had done in

their time.

As we reflect upon the past, we are reminded that

each generation is challenged with different circumstances,

which calls for different responses. If we are going to be

successful, we have to be fully cognizant of that at all

times.

The American Indian Policy Review Commission

is not well known to many people and yet it had a significant impact articulating a new vision for our people. Senator James Abourezk and Senator Fred Harris were major

catalysts in having Congress reluctantly initiate and fund

this monumental undertaking of examining policies across

the board in education, natural resources protection, and

governance, among the most critical areas of policy development. It brought together a Who’s Who in Indian Country and brought together an unprecedented group of the

best thinkers and radical thinkers of the time. Their recommendations were far-reaching to this day. It was the planting of seeds for a new era. It was, for the first time, from

and through our lens. It helped to usher in what we know

today as the “self –determination era.”

After its implementation into law by President

Richard Nixon in 1975, self-determination policy didn’t

really take full form until the early mid-80s in two distinctively different ways. One was becoming fully conscious

of effectuating the intent of the law, and assuming the responsibility of managing and administering programs once

the responsibility of the federal government, predominantly

through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The other would

happen much later, and would conceptually extend the experience, opportunities, and principles to state-tribal relations.

What would force the latter was the implementation of the state rights agenda that would ironically cause a

conflict, perhaps as an unintended consequence, between

the states and the tribes. This agenda would consciously

dismantle the community block grant framework that heretofore had resulted in a relationship between the federal

government and tribal governments as resources flowed

directly to the tribes.

Beginning with the Welfare Reform Act, the shift

was more pronounced. There was a very interesting question asked in this development and discourse in regard to

10

I - N ew s

A Conversation with Regis Pecos, Part 1:

The Emergence of Federal Self-Determination Policy and its Impact in Defining State-Tribal Relations

Indian people. In came at a time when Contract With

America was evolving and a conservative think-tank, The

Heritage Foundation, in this individual responsibility

agenda would ask, “Isn’t it about time we gave the American Indian his rightful place?” On the face of it, who

would object, right? So here we were in the midst of a new

policy of self-determination with contradicting policies at

play at the same time. What was implied, of course, like

with termination and relocation, was that we ought to be

totally assimilated and be responsible for ourselves, and

integrated into mainstream society. At the time here in

New Mexico, we recognized that a message needed to be

heard on Capitol Hill.

Senator Daniel Inouye, who had just become

Chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and

Alan Parker, an Indian himself, who was Chief Counsel at

the time, understood the underlying ramifications these

new ideas would cause. So, we traveled to Washington.

Tribal leaders, Representative Nick Salazar, would testify

that even in places like New Mexico, where relationships

were generally positive, unless there were explicit provisions guiding how states and tribes would work together to

implement and access resources for this newly defined program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

(TANF), it would pose significant problems between states

and tribes. It was a state’s rights agenda and sure enough,

even to this day, matters are not fully resolved. It did cause

a major conflict.

We have to appreciate that, historically, states had

not yet been defined in this governmental framework. It

was a federal/state or federal/tribe system, not yet integrating federal, state, and tribal governments. In fact, many

would say at that time that states were the worst enemies of

tribal governments for the simple fact that tribes and states,

often in trying to carve out their respective places as sovereign governments, defined the relationship or nonrelationship litigiously in the courts as they over battled

who had the great power and/or authority as sovereign governments.

It was welfare reform that finally forced a relationship between states and tribes. Programatically, welfare

reform hit hard at the heart of our cultural organization and

our extended family structures. The next wave was health

care reform. In both cases, resources would flow through

the states. This was a bigger heartburn than anyone had yet

experienced. Indian Health is one of the longstanding pillars tribes define as part of a trust obligation on the part of

the federal government to Indian people. Tribal leaders

fought that fight but lost and the Health Care Reform Act

would force another relationship if Indian people, eligible

for these services, were going to get their fair share.

What would happen if we use this service through

the state? Will the federal government use this to dismantle Indian Health Service (IHS)? Others would say that we

have dual citizenship, and that we therefore ought to have

the benefit of services from both the IHS, and, where some

services are not possible with diminishing federal support,

we ought to also have the right, as citizens of New Mexico,

if we qualify, to enjoy the benefits provided by the state.

These issues and questions gave rise to a new appreciation

that tribal leaders would now be forced to focus their attention to defining our relationship with the state. Given the

history, we had a right to feel schizophrenic. These were

very important questions Indian people were asking their

leaders.

What motivated states and tribes to begin working

together collaboratively was appreciating that they had to

define a whole different approach to addressing competing

interests. With a state rights agenda forcing the state and

tribes into an undefined relationship and, as tribes were

flexing their muscle and their powers and authority under

self-determination laws, there were sharp conflicts but

there were also some extraordinary visionaries who

emerged and created a framework to guide the development of these relationships that deserve credit of their profound wisdom. While tribes were fighting at the federal

level, there were leaders here at the state level who were

heading major initiatives to develop a framework within

which tribal and state leaders would engage in a necessary

discourse over issues of mutual concern and interest. For

example, Governor Tony Anaya in the early 80’s was one

who began engaging tribal leaders formally on important

state-tribal issues on education. He and then Navajo Nation President Peterson Zah would sign the first State/

Tribal Protocol Agreement. Sam Deloria, the Director for

the American Indian Law Center, used the Center as a vehicle to create a national movement with the creation of the

Commission of State/Tribal Relations. The work that ensued through these kinds of initiatives gave guidance in the

early stages of the development and evolution of New

Mexico’s state-tribal relations and protocols.

Please see “A Conversation with Regis Pecos,

Part 2,” in the February issue of I-News.

Printed with permission from Regis Pecos.

©Copyright 2009, Regis Pecos. All rights reserved.

The views expressed in this interview do not

necessarily reflect the opinions or the official policy or

position held by the Indian Affairs Department or the

11

State of New Mexico.

I - N ew s

New

Mexico

Tribal

Liaison

Bulletin:

Secretary

Rhonda

Faught

Advanced

the

Role andon

Importance

State-Tribal

Reflecting

the Indianof

Child

Welfare Relations

Act of 1978

tutions. The decision to remove these children from their

natural families was often a lack of understanding of Indian

culture and child-rearing practices (U.S. House Report,

1978).

Recent news articles and reports have created a

The AAIA study found that Indian children were

misunderstanding of State child custody proceedings infive (Minnesota) to sixteen times (Montana) more likely to

volving Indian children. The following is a broad attempt

to highlight the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978. be placed in foster care compared to non-Indian children.

A survey of 16 states in 1969 also revealed that

Because Indian children are treated uniquely in the

legal system, and because there is an increasing number of approximately 85% of Indian children in foster homes and

90% of non-relative Indian adoptees were living with noncourt proceedings involving Indian children, the need to

understand the ICWA is fast becoming imperative. (Since Indian families (U.S. House Report, 1978). The result of

this survey troubled tribes for a variety of reasons. First,

the ICWA was enacted, more than 250 state and federal

the placement of so many Indian children in non-Indian

court decisions have been rendered.)

homes threatened the extinction of the tribe. In short, tribes

were losing the most basic necessity for survival – a next

Historical Development of ICWA

generation.

In 1974 Congress initiated its first hearing on the

As early as 1860, the Bureau of Indian Affairs

(BIA) used boarding schools as federal policy to “civilize” state of Indian children in substitute care. Testimony in

1974 provided the first official acknowledgement by the

Indian children by separating them from their tribal comUnited States government that the unwarranted removal of

munities and forcing them to learn English and to adopt

Indian children from their families represented a systematic

European-American practices and customs. Further, in

attempt to destroy Native tribes and cultures that resulted in

1958, the BIA and the Child Welfare League of America

negative outcomes for both tribes and tribal children.

(CWLA) established the Indian Adoption Project to

On November 8, 1978 Congress passed the Indian

“provide adoptive placements for Indian children whose

parents were deemed unable to provide a “suitable” home Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in response to the “rising concern … over the consequences to Indian children, Indian

for them. States were paid by the BIA to remove Indian

families, and Indian tribes of abusive child welfare pracchildren from their homes under the charge of neglect.

Most of the children removed from their “unsuitable” envi- tices that resulted in the separation of large numbers of Indian children from their families and tribes through adopronment were placed in non-Indian homes.

tion or foster care placement.” By limiting states’ powers

In 1968, members of Spirit Lake Sioux Tribe of

over American Indian children, ICWA aims to support InNorth Dakota were concerned with the treatment of their

children by their local state child welfare officials. Due to dian families, specifically by maintaining Indian children

with Indian caregivers in order to honor a rich cultural trawhat the tribe perceived as the state’s ignorance of tribal

dition and tribal sovereignty.

welfare practices, tribal children were routinely uprooted

from their Indian families and placed in non-Indian foster

or adoptive homes, a situation exacerbated by the fact that What ICWA Requires of States

many of the actions taken by state child welfare agents

were carried out without tribal consultation.

As mentioned in the Act, Congress designed

From 1969 through 1974, the Association on

ICWA to restrain the authority of state agencies and courts

American Indian Affairs (AAIA) acting at the request of

in removing and placing Indian children, based on states ”

the Spirit Lake Tribe, conducted nationwide studies on the historical inability to fairly adjudicate child custody proimpact of state child welfare practices toward Indian chil- ceedings” (25 U.S.C. 1901(5); Native Village of Venetie

dren. AAIA research indicated that in certain states, 25%- I.R.A. Council v. Alaska, 1991). ICWA accomplishes this

45% of all Indian children were removed from their natural task through both procedural and substantive provisions

homes and placed in foster homes, adoptive homes or insti- that advance Congress’ purpose of protecting Indian chilBy Bernie Teba, Tribal Liaison,

Children, Youth, and Families Department

12

I - N ew s

New Mexico Tribal Liaison Bulletin:

Reflecting on the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, cont.

dren and tribes by “ the establishment of minimum federal

standards for the removal of Indian children from their

homes and families and the placement of such children in

… homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian

culture” (25 U.S.C. 1902).

ICWA is unique in that it involves not only the

relationship between American Indian tribes and the federal government but also the relationship of state government to both the United States government and tribes.

In its broadest application, ICWA applies only to

child custody proceedings in state court systems. Under

ICWA, a child custody proceeding includes foster care

placement, termination of parental rights, pre-adoptive

placement and adoptive placement (25 U.S.C. 1903[1]).

The Act further specifies that the child involved in

a custody proceeding must be “Indian” (25 U.S.C. 1903[4])

and requires that the child in question be an unmarried minor who is either (a) a member of an Indian tribe, or, (b)

eligible for membership in a tribe, AND a biological child

of a tribal member. If a child is a member of, or eligible for

membership in, more than one tribe, the court must decide

the child’s tribe for ICWA purposes by determining the

tribe with which the child has “the most significant contacts” (25 U.S.C. 1903[5]).

To protect the interests of tribes, ICWA requires

states to provide notification to the tribe at least 10 days in

advance of pending “involuntary” child custody proceedings (25 U.S.C 1912[a]). This requirement is consistent

with the fundamental underpinning of ICWA that recognizes that tribes have a unique interest separate from that of

the child’s parent or Indian custodian.

ICWA also requires states to document the placement history of Indian children within their respective child

welfare systems. In cases of adoption, ICWA authorizes

Indian children, once they reach 18 years of age, the right

to obtain information on their tribal heritage (25 U.S.C.

1915 [e], 1917 and 1951)

Consequently, 25 U.S.C 1911 of ICWA grants tribes exclusive jurisdiction in all child custody matters involving Indian children who are wards of tribal courts or who reside

or domiciled on Indian reservations. Also, if an Indian

child is the subject of a foster care placement or termination of parental rights proceeding in state court, the state

must transfer the proceeding to the tribe, absent objection

by either parent, upon petition by either parent, Indian custodian or tribe (25U.S.C 1911 [b]). This transfer should

occur absent “good cause to the contrary”. The Supreme

Court has ruled that the jurisdiction of the tribal court in

such cases is “presumptive” meaning that good cause to the

contrary should be a heavy burden for the state to carry.

ICWA also strengthens the legitimacy of tribal

courts in conducting child welfare proceedings involving

Indian children. ICWA provision 25 U.S.C 1911[d] requires that both state and federal courts give “full faith and

credit” to tribal acts, records and judicial proceedings in the

same manner afforded to non-Indian entities (such as

courts of other states).

Although ICWA protects the legal interests of

tribes and provides for the “best interests” of Indian children in state custody - without Indian families to serve as

foster care and adoptive families - history will repeat itself.

Joint Tribal- State collaborative efforts are necessary for

the successful implementation of the ICWA of 1978.

As one result of the 1995 U.S. General Accounting

Office survey of States’ Compliance with ICWA, CYFD

revised the ICWA Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) by

and between the Navajo Nation and CYFD. Both Navajo

Nation and CYFD agreed that the revision was a historic

occasion since it had been over 20 years since the last

ICWA IGA had been revised. The revised ICWA IGA

more clearly defines the roles and responsibilities of the

Navajo Nation and CYFD. The process involved in revising the ICWA IGA included key elements in Governor

Richard’s executive order 2005-004 and the 2003 Statement of Tribal-State Government-to-Government Policy.

Jurisdiction and Requests for Transfer

In Mississippi Band of Choctaws v. Holyfield

(1989), the U.S. Supreme Court noted that the jurisdictional mandates of ICWA are at the very heart of the Act.

The jurisdictional provisions of ICWA are designed to

maximize the opportunity for tribal courts to determine the Bernie Teba is the CYFD Tribal Liaison and ICWA contact

fate of their children because such courts are the more

and can be reached at 505-827-7612 or by e-mail at

knowledgeable about child-rearing traditions and customs. Bernie.Teba@state.nm.us

13

I - N ew s

Behavioral Health Collaborative Approves

Expansion of Local Collaboratives

Governor Bill Richardson Announces Expanded

Education Initiatives for 2009 Legislative Session

The Behavioral Health Collaborative has approved

a proposal for the expansion of Native American Local

Collaboratives by three, which will increase the number of

Native American Local Collaboratives to five, and the total

number of Local Collaboratives to 18 across the state.

Governor Bill Richardson outlined

his expanded education agenda for the upcoming legislative session during visits to Clovis and Tucumcari. While

speaking with lawmakers, community leaders, education

officials and students, the Governor reiterated his support

for changing the current education funding formula and

announced his proposals to increase college opportunities

for New Mexico students.

“We have no higher priority than ensuring all New

Mexico students receive a quality education and are given

the tools and opportunities for success,” Governor Richardson said. “I look forward to working with the legislature to

make sure we are adequately funding our classrooms, but

ultimately I believe the voters of New Mexico must have a

say on this major investment.”

Two years ago, Governor Richardson signed legislation to fund a task force to study the funding formula that

New Mexico has used for more than 30 years. It found the

funding formula is outdated and underfunds schools, particularly smaller and rural schools, by $350 million. The

Governor will work with lawmakers to find a way so that

voters decide how changes to the formula will be funded.

Other educational initiatives the Governor will be

pushing for this year include:

• Requiring students to be in the classroom 180 days and

moving teacher professional development outside of

the instruction day.

• Increasing math requirements for K-8 teachers by three

credit hours.

• Strengthening the Public Education Department’s ability to sanction school districts that do not adhere to

audit requirements.

• Expanding the College Affordability Fund Scholarship

to increase the number of students who can receive

assistance.

• Put all of the state’s 3% Scholarships into need-based

aid.

• Creating a division within the Higher Education Department to coordinate all major initiatives targeted

towards Native American Students.

• Expand dual credit opportunities so that Native American high school students can take advanced classes and

earn credit toward graduation at Tribal and other colleges.

Using proposals, assessment of readiness, and geography as the criteria, the Collaborative selected the following three proposals for the Local Collaborative expansion.

1.

Rain Cloud, an off reservation group,

2.

Sandoval County Consortium (Santa Ana, Santo

Domingo, Zia, Cochiti, Jemez, Sandia, and San Felipe

Pueblos as well as urban tribal populations in Sandoval

County), and

3.

Eight Northern Pueblos - with the stipulation they

must provide a list of members (Nambe, Picuris, Pojoaque, San Ildefonso, Ohkay Owingeh, Santa Clara,

Taos and Tesuque Pueblos).

The Jicarilla Apache Nation, who also submitted a

proposal for a Local Collaborative, will be given the option

to join one of the three expansion collaboratives, or remain

a part of Local Collaborative 14. Any Local Collaborative

must accept Jicarilla Apache Nation and all Local Collaboratives must affirm their willingness to be inclusive and not

refuse anyone’s participation.

This expansion leaves Local Collaborative 14 with

more geographic integrity with Mescalero Apache Tribe

and the southernmost Pueblos (Isleta, Acoma, Laguna and

Zuni Pueblos) and Navajo Chapters (Ramah, Alamo and

To’Hajiilee.) The Mescalero Apache Tribe proposal that

was submitted was very strong and this expansion plan is

intended to recognize their strength and maintain geographic integrity.

About the Collaborative

The Collaborative was created in 2004 by the Governor and the Legislature to allow most state agencies and

resources involved in behavioral health treatment and recovery to work as one in an effort to improve mental health

and substance abuse services in New Mexico. This cabinetlevel group represents 15 agencies and Governor Bill

Richardson’s office.

Contact: Betina Gonzales McCracken (505) 476-6205

Alarie Ray-Garcia, Office of Governor Bill Richardson

14

I - N ew s

Governor Bill Richardson Announces Public Safety Priorities for Legislative Session

Governor Bill Richardson traveled around the state

on January 14 to announce his public safety priorities for

the legislative session. The Governor stopped in Farmington, Las Cruces and Roswell where he detailed his plans

for tougher DWI, Liquor Control, gangs and domestic violence reforms.

“Today I outlined my ambitious plan to improve

public safety in New Mexico, including increasing penalties for drunk driving, domestic violence and gang violence

and new this year – we are proposing legislation to combat

drugged driving,” Governor Richardson.

DWI

Governor Richardson today proposed a number of

new DWI initiatives to be presented to the Legislature later

this month. The Governor announced his proposal to combat “drugged drivers” – including a bill that would establish a limit for drivers under the influence of illegal drugs.

The Governor is also proposing a bill that would

allow law enforcement officers to appear by phone or

video conference in order to participate in DWI license

revocation hearings. This would allow officers to stay on

in communities looking for drunk drivers instead of spending valuable time in court.

Liquor Control Act

The Governor along with DWI Czar Rachel

O’Connor unveiled plans for more comprehensive liquor

control reform in Farmington this morning.

“This year we're bringing forward a bill that provides for comprehensive liquor reform for the Liquor Control Act in the State of New Mexico,” said Governor

Richardson. “This bill will have provisions that substantively impact public safety and liquor licensing.”

The proposed changes would bring an increase in

financial penalties to bars that over serve and sell to minors; both are violations under the Three Strikes rule. The

legislation also would allow the state to revoke the liquor

licenses of establishments that are considered a public nuisance.

Additional changes to the Liquor Control Act

would give local law enforcement the authority to enforce

certain provisions of act and would require alcohol servers

to renew their server permits every three years instead of

every five.

Gangs

The Governor has proposed two pieces of legislation aimed at fighting back against gangs in New Mexico. The first will make gang recruitment a crime. We

want to make recruiting an adult into a gang a 4th degree

felony and recruiting a child a 3rd degree felony.

Secondly, the Governor has proposed a bill that

would provide sentence enhancements for crimes committed during gang activity. Under this bill gang activity penalties will be increased from a one year enhancement for a

fourth degree felony to an additional eight years for a first

degree felony. This will give police and prosecutors better

tools to prosecute those individuals who have not gotten

the message, “We don’t want gang violence here.”

Domestic Violence

The Governor announced a number of new domestic violence initiatives during his stops around the state

today. The first is to add domestic violence to a list of

crimes that would limit an individual’s ability to obtain

certification as a law enforcement officer or to retain their

certification.

Secondly, the Governor wants to close a major gap

in the current law and make damage to community or

jointly owned property a crime the Governor wants take

power away from batterers. This bill would create a new

offense under the Crimes Against Household Members Act

making criminal damage to property against a household

member a 4th degree felony if the damage is more than

$1000.

The Governor also unveiled his plan to prohibit

employers from discriminating against victims of domestic

violence, sexual assault and stalking. Under the Governor’s

proposed bill, employers must grant employees unpaid

leave to obtain an order of protection or other judicial relief

from abuse, to meet with law enforcement, consult with

attorneys or victim advocates and attend court proceedings

related to the abuse.

Finally, with one in twelve New Mexicans being

victimized by stalkers and only 5.5% of these cases resulting in an arrest, the Governor is looking to streamline and

broaden the language in our stalking law so that stalkers

will no longer be able to threaten or cause fear to their victims.

Alarie Ray-Garcia, Office of Governor Bill Richardson

15

I - N ew s

Welcome New and Continuing 2009 Tribal Officials!

2009 TRIBAL OFFICIALS

Tribes, Pueblos, and Nations in

New Mexico:

(in alphabetical order)

JICARILLA APACHE NATION

PRESIDENT LEVI PESATA

P.O. Box 507

Dulce, NM 87528

Phone (575) 759-3242

Fax (575) 759-3005

Vice President Ty Vicenti

MESCALERO APACHE TRIBE

PRESIDENT CARLETON NAICHEPALMER

P.O. Box 227

Mescalero, NM 88340

Phone (575) 464-4494

Fax (575) 464-9191

Vice President Jackie D. Blaylock, Sr.

NAVAJO NATION

PRESIDENT JOE SHIRLEY, JR.

P.O. Box 9000

Window Rock , AZ 86515

Ph on e (928) 871-6352/6357

Fax (928) 871-4025

Vice President Ben Shelly

NAVAJO NATION COUNCIL

Speaker Lawrence T. Morgan

P.O. Box 3390

Window Rock , AZ 86515

Phone (928) 871-7160

Fax (928) 871-7255

OHKAY OWINGEH

GOVERNOR MARCELINO AGUINO

P.O. Box 1099

San Juan Pueblo, NM 87566

Phone (505) 852-4400/4210

Fax (505) 852-4820

1st Lt. Gov. Virgil Cata

2nd Lt. Gov. Joseph Martinez

PUEBLO OF ACOMA

GOVERNOR CHANDLER SANCHEZ

P.O. Box 309

Acoma, NM 87034

Phone (505) 552-6604/6605

Fax (505) 552-7204

1st Lt. Gov. Mark Thompson

2nd Lt. Gov. Ron Charlie

PUEBLO OF COCHITI

GOVERNOR JOHN F. PECOS

P.O. Box 70

Cochiti Pueblo, NM 87072

Phone (505) 465-2244

Fax (505) 465-1135

Lt. Gov. Peter Trujillo

PUEBLO OF ISLETA

GOVERNOR ROBERT BENAVIDES

P.O. Box 1270

Isleta Pueblo, NM 87022

Phone (505) 869-3111/6333

Fax (505) 869-4236

1st Lt. Gov. Max Zuni

2d Lt. Gov. Frank Lujan

PUEBLO OF JEMEZ

GOVERNOR DAVID TOLEDO

P.O. Box 100

Jemez Pueblo, NM 87024

Phone (575) 834-7359

Fax (575) 834-7331

1st Lt. Gov. Benny Shendo, Jr.

2nd Lt. Gov. Stanley Loretto

PUEBLO OF LAGUNA

GOVERNOR JOHN ANTONIO, SR.

P.O. Box 194

Laguna Pueblo, NM 87026

Phone (505) 552-6654/6655/6598

Fax (505) 552-6941

1st Lt. Gov. Robert Mooney, Sr.

2nd Lt. Gov. Marvin Trujillo, Jr.

PUEBLO OF NAMBE

GOVERNOR ERNEST MIRABAL

Route 1, Box 117-BB

Santa Fe, NM 87506

Phone (505) 455-2036

Fax (505) 455-2038

Lt. Gov. Arnold Garcia

PUEBLO OF PICURIS

GOVERNOR RICHARD MERMEJO

P.O. Box 127

Penasco, NM 87553

Phone (575) 587-2519

Fax (575) 587-1071

Lt. Gov. Matthew Pacheco

PUEBLO OF POJOAQUE

GOVERNOR GEORGE RIVERA

Pueblo of Pojoaque

78 Cities of Gold Road

Santa Fe, NM 87506

Phone (505) 455-3334

Fax (505) 455-0174

Lt. Gov. Linda Diaz

PUEBLO OF SANDIA

GOVERNOR JOE M. LUJAN

481 Sandia Loop

Bernalillo, NM 87004

Phone (505) 867-3317

Fax (505) 867-9235

Lt. Gov. Scott Paisano

PUEBLO OF SANTA ANA

GOVERNOR BRUCE SANCHEZ

2 Dove Road

Santa Ana Pueblo, NM 87004

Phone (505) 867-3301

Fax (505) 867-3395

Lt. Gov. Myron Armijo

PUEBLO OF SANTA CLARA

GOVERNOR WALTER DASHENO

P.O. Box 580

Espanola, NM 87532

Phone (505) 753-7330/7326

Fax (505) 753-8988

Lt. Gov. Bruce Tafoya

PUEBLO OF SAN FELIPE

GOVERNOR ANTHONY ORTIZ

P.O. Box 4339

San Felipe Pueblo, NM 87001

Phone (505) 867-3381/3382

Fax (505) 867-3383

Lt. Gov. James Candelario

PUEBLO OF SAN ILDEFONSO

GOVERNOR LEON T. ROYBAL

Route 5, Box 315-A

Santa Fe, NM 87506

Phone (505) 455-2273

Fax (505) 455-7351

1st Lt. Gov. Paul Rainbird

2nd Lt. Gov. Terrence K. Garcia

PUEBLO OF SANTO DOMINGO

GOVERNOR EVERETT F. CHAVEZ

P.O. Box 99

Santo Domingo Pueblo, NM 87052

Phone (505) 465-2214

Fax (505) 465-2688 /-2215

Lt. Gov. Paul Rosetta

Pueblo Organizations:

ALL INDIAN PUEBLO COUNCIL

CHAIRMAN JOE GARCIA

2401 12th Street, NW

Albuquerque, NM 87103

Phone (505) 881-1992

Fax (505) 883-7682

Vice Chairman Gregory T. Ortiz

EIGHT NORTHERN INDIAN PUEBLOS COUNCIL

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

MICHAEL MILLER

P.O. Box 969

San Juan Pueblo, NM 87566

Phone (505) 747-1593

Fax (505) 747-1599

FIVE SANDOVAL INDIAN PUEBLOS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

JAMES ROGER MADALENA

1043 Highway 313

Bernalillo, NM

Phone (505) 867-3351

Fax (505) 867-3514

PUEBLO OF TAOS

GOVERNOR RUBEN A. ROMERO

P.O. Box 1846

Taos, NM 87571

Phone (575) 758-9593

Fax (575) 758-4604

Lt. Gov. Tony R. Mirabal

PUEBLO OF TESUQUE

GOVERNOR MARK MITCHELL

Route 42, Box 360-T

Santa Fe, NM 87506

Phone (505) 955-7732

Fax (505) 982-2331

Lt. Gov. Earl Samuel

PUEBLO OF ZIA

GOVERNOR IVAN PINO

135 Capitol Square Dr.

Zia Pueblo, NM 87053-6013

Phone (505) 867-3304

Fax (505) 867-3308

Lt. Gov. Fred Medina

PUEBLO OF ZUNI

GOVERNOR NORMAN COOEYATE

P.O. Box 339

Zuni, NM 87327

Phone (505) 782-7022

Fax (505) 782-7202

Lt. Gov. Dancy Simplicio

16

I - N ew s

The Interim Indian Affairs Committee

(IIAC)

2009 Legislative Shuttle

The goals of the Interim Indian Affairs Committee are FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE…

to: provide a direct interface between the legislature

and tribal governments and officials in New Mexico;

The New Mexico

identify issues of concern to American Indian people

Department of Transportation

and tribal communities and provide information to

is operating the

legislators regarding those issues; provide legislators

with first-hand information regarding the status of

2009 LEGISLATIVE SHUTTLE

tribal communities in New Mexico; provide the peothrough March 20, 2009

ple living in tribal communities with an understanding

NO FARE

of and access to state government; identify and work

to resolve areas of state-tribal misunderstanding, conFREE at all times

flict and dispute, and; identify areas where state government can be made more responsive to the needs of

There are three shuttle routes: