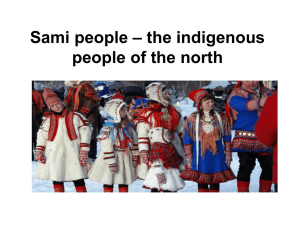

the sami – an Indigenous People in Sweden

advertisement