when big business meets feng shui, superstition and

advertisement

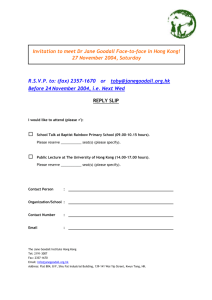

PART A go online Go online to <www.pearsoned.com.au/fletcher> to find more cases. CASE STUDY 3 Hong Kong Disneyland: when big business meets feng shui, superstition and numerology 124 John Kweh, School of Marketing, University of South Australia and Justin Cohen, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, University of South Australia E N V I R O N M E N TA L A N A LY S I S O F I N T E R N AT I O N A L M A R K E T S BACKGROUND Disney, one of the world’s most recognised brands, launched its most recent theme park in Hong Kong in 2005. Hong Kong Disneyland, the fifth theme park globally, was created to service the Hong Kong market, but more strategically to reach the rapidly growing Chinese market. Hong Kong Disneyland is located on Lantau Island, 10 minutes from the Hong Kong International airport and 30 minutes from the city via the subway (Holson 2005). The theme park is a joint venture between the Walt Disney Co. and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) government (Landreth 2005). The theme park is Disney’s smallest at 745 hectares, but still consists of four distinct entertainment arenas: Main Street USA, Fantasyland, Adventureland and Tomorrowland. Hong Kong Disneyland is based on the Anaheim, California original (Landreth 2005). Hong Kong has been chosen as the steppingstone into the vast Chinese market as most Chinese have not grown up with Disney (Miller 2007). Another theme park in Shanghai is tentatively planned for 2010. Hong Kong, a capitalist economy where English is prevalent, maintains a sound legal and judiciary system and good corporate governance (Fong 1995). Thus Hong Kong has been an ideal choice for many corporations to launch into China. PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts a 25.2% rise in Chinese entertainment and media spending through to 2009, making China the fastest growing market for entertainment in Asia (Landreth 2005). This can be attributed to the rapid growth of the middle class in China, compounded with the reinvestment of money by overseas Chinese in their now-flourishing country. MICKEY MOUSE GOES GLOBAL In 1983, Tokyo Disneyland was launched in Japan with a huge success. This seemed to bode well for Disney because it cloned its American theme park and reproduced it in Tokyo. Unfortunately, this proved to be a false sense of security for its overseas expansion. Disney next set its sights on a market and culture much closer to home. Its next project was Euro Disney, launched in Paris in 1992. Cultural sensitivity issues marred EuroDisneyland (now known as Disneyland Paris) from the first day. Disney was accused of ignoring French culture and criticised for exporting American imperialism in its European venture (Brennan 2004) The issues regarding language, alcohol consumption and pricing of tickets and merchandise damaged the Disney brand (Brennan 2004). Euro Disney received negative publicity and headlines such as ‘Disney is cultural Chernobyl’ (‘The horns of a dilemma’, Economist, In order to reach a balance between Disney tradition and French culture, Stephen Burke, the then vice president in charge of park operations and marketing at EuroDisney made a number of changes to retain Disney’s image while still adapting to the French culture. First, the name EuroDisney was changed to a more nationalistic Paris Disneyland, so that the French would be more receptive to it (Anonymous 1998). Burke’s strategies to retain Disney’s image included: • focusing on hiring an outgoing and friendly Disney cast; • increased training; • the placement of additional Disney characters throughout the park. Burke’s strategies to adapt Disney to the French culture included: • removing the ban on alcohol in the theme park; • lowering the corporate Disney premium on admission, merchandise, hotels and food; • relaxing Disney’s hierarchical management structure; DISNEY FOLLOWS MULAN HOME Disney had one great success and one great failure in its international expansion. Its next launch had to succeed at all costs. This time Disney was prepared for a long planning period. Disney now knew that it must consider the various cultural nuances and sensitivities of its host nation. The design of Hong Kong Disneyland took into account Chinese cultural aspects and planners went to great lengths to ensure that it was well received by the local Hong Kong population and their projected mainland Chinese visitors (Fowler and Marr 2005). Hong Kong Disneyland focused on three core markets: Hong Kong residents, visitors from the southern part of China and visitors from South-East Asian markets (Emmons 2001). Table 1 clearly shows the value of these three markets, but most importantly the rapid rise in visitors to Hong Kong from mainland China. Although people from Hong Kong live with cutting edge technology, superstition still plays a vital part in their culture. Numbers and feng shui are taken seriously in all aspects of everyday life and business. FENG SHUI, SUPERSTITION AND NUMEROLOGY Hobson (1994) discussed the influence of feng shui on the Asian hospitality industry. It has been noted that the location, interior and exterior of the building are important factors to be considered. Rossbach (1984) stated that the Chinese see a link between humanity and the earth whereby everything is interconnected and needs to be in balance. Buildings and other structures need to blend into the landscape to ensure that there is a good flow of energy or ‘qi’. The five elements of feng shui (water, wood, fire, earth and metal) have been incorporated into the Hong Kong Disneyland design (see Figure 1). Tom Morris, chief designer, said, ‘Regarding feng shui, the thing that is most visible is the heavy usage of water in the park’ (‘Disney uses feng shui to build Mickey’s new kingdom in 125 C AT E R I N G F O R T H E C U LT U R A L A N D S O C I A L E N V I R O N M E N T O F I N T E R N AT I O N A L B U S I N E S S THE FRENCH REVOLUTION: LEARNING TO BREAK BREAD OR BAGUETTES • cutting managerial staff by almost 1000 in order to flatten management and empower the employees (Anonymous 1998). CHAPTER 3 November 1992). There were continuous protests from French farmers because of the French government’s acquisition of farmland for the Disney theme park (Anonymous 1998). Workers resisted the Disney management style and dress code (Anonymous 1998). These incidents made Disney aware that venturing into non-American markets could be extremely complex due to cultural differences. This outcome startled Disney. How could a copycat launch of their product in an Eastern country with vast cultural differences succeed, but yet fail immensely in a Western European market? Disney had global recognition and an association with fun and family, but senior managers and strategists now understood that they needed to truly understand the cultures of their host nations. PART A TABLE 1 Visitor arrivals to Hong Kong by country/territory of residence 2001 2005 Visitors (’000) 2006 The mainland of China 4 449 12 541 13 591 Taiwan 2 419 2 131 2 177 South & Southeast Asia 1 747 2 413 2 660 North Asia 1 762 1 853 2 030 The Americas 1 259 1 565 1 631 Europe, Africa & the Middle East 1 171 1 726 1 917 Macao 532 510 578 Australia, New Zealand & South Pacific 387 620 668 13 725 23 359 25 251 (+5.1) (+7.1) (+8.1) Country/territory of residence Total SOURCE: Census and Statistics Department (2007) Hong Kong in Figures, Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. FIGURE 1 The five elements of feng shui and how they interact s De st Destroys ult h cy cle ( Insults De s Ins De s ult st r oys ults Ins Des troy s Ins (C u) W +GB WOOD Crushing (Beng) –LV Insu ltin g act ing cy cle g) c ion Ove r s troy ct ru e) e (K ycl Insu lt a nc tio +SI +TH FIRE Exploding (Pao) –HT –PC ) eng (Sh le yc en Cr e CYCLES OF GENERATION AND CONTROL Des E N V I R O N M E N TA L A N A LY S I S O F I N T E R N AT I O N A L M A R K E T S 126 str oys +UB WATER Drilling (Zuan) –KD +LI METAL Splitting (Pi) –LU CYCLES OF IMBALANCE SOURCE: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:FiveElementsCycleBalanceImbalance.jpg>. +ST EARTH Crossing (Heng) –SP Bibliography Brennan, Y.M. (2004) ‘When Mickey loses face: recontextualization, semantic fit, and the semiotics of foreignness’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 583–616. Anonymous (1998) ‘Balancing tensions: Stephen Burke’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40, No. 1, p. 27. 127 C AT E R I N G F O R T H E C U LT U R A L A N D S O C I A L E N V I R O N M E N T O F I N T E R N AT I O N A L B U S I N E S S on 12 September 2005, at exactly 1 p.m., a date and time believed to be most auspicious according to the Chinese Almanac (Miller 2007). Apart from lucky numbers, the Chinese love the colour red due to its symbolic representation of prosperity; that is why it is seen throughout the theme park. Chinese taboo and superstition have been taken into consideration as well. Certain merchandise is not sold in the park. Clocks are nowhere to be seen because giving a clock as a gift is strictly forbidden in Chinese culture—it is a bad omen and insinuates that one will go to a funeral. Green hats are also not on sale. This is because a man wearing a green hat symbolises that his partner has committed adultery (‘Disney uses feng shui to build Mickey’s new kingdom in Hong Kong’ 2005). Besides feng shui, many adaptations have been made to better suit Chinese visitors. Its employees are culturally diverse and many speak a number of languages. Hong Kong Disneyland is officially trilingual with English and two dialects of Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese), which are used in all signage and audio-recorded messages (Einhorn 2005). Euro Disneyland on the other hand had an English-only policy for staff when it first opened (Brennan 2004). Chinese food is also abundant in the theme park. Although Western food such as hotdogs, hamburgers and candyfloss is served, lots of local delicacies can be enjoyed as well. Don’t be surprised to come across soy sauce chicken wings or black sesame ice cream! Disney has now launched its theme parks in three international markets. Each experience has been unique. Tokyo Disneyland was clearly beginner’s luck. Paris Disneyland proved to be one of the company’s biggest blunders. Changes have been made, but the Paris operation has never yielded their projected returns. Hong Kong Disneyland is truly a marriage of East and West. Thus far, the venture has been successful, but time will tell. Disney has looked to the past to secure its future. CHAPTER 3 Hong Kong’ 2005). The Chinese, in many cases, would attribute business failure to bad feng shui— hence few dare to ignore it. The fundamental feng shui principle is to create harmony between humanity and the earth. Feng shui principles have been adopted in the placement, orientation and design of the park. A geomancer, a feng shui specialist, was consulted before the construction of the theme park began (Miller 2007). Feng shui practices at Hong Kong Disneyland are prevalent. The main entrance gate of the theme park was shifted 12 degrees to maximise good energy flow (Holson 2005). Ritual incense burning was customary upon the completion of each building (Holson 2005). Boulders have been placed throughout the theme park to represent stability. A bend was also created in the walkway from the train station; this was believed to ensure that good fortune does not flow out the back of the park (Holson 2005). To ensure a balance of the five elements of feng shui, some areas have been designated as ‘no fire zones’ (Lee 2005). This meant that Disney had to ensure that there were no kitchens in these areas (Lee 2005). The theme park has no fourth floor as the number ‘four’ sounds the same as the word ‘death’ in Cantonese and Mandarin and is considered unlucky (Yardley 2006). On the other hand, the number eight, considered lucky, is used extensively (Yardley 2006). It signifies prosperity and wealth. For example, the main ballroom of one of the hotels is 888 square feet (Ho 2006). There are 2238 crystal lotuses that decorate one of the restaurants. When one pronounces the number ‘2238’ in Cantonese, the sound strongly mimics the Chinese phrase for ‘becoming wealthy with ease’ (‘Disney uses feng shui to build Mickey’s new kingdom in Hong Kong’ 2005). Numbers play an important role in Chinese culture and it is no coincidence that the Summer Olympics in Beijing are scheduled to open on 8/8/8 at 8 p.m. (Yardley 2006). Hong Kong Disneyland opened PART A E N V I R O N M E N TA L A N A LY S I S O F I N T E R N AT I O N A L M A R K E T S 128 Census and Statistics Department (2007) Hong Kong in Figures, Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. ‘Disney uses feng shui to build Mickey’s new kingdom in Hong Kong’ (2005), <http://english.sina.com/taiwan_ hk/1/2005/0907/45097.html>, accessed 27 April. Einhorn, B. (2005) ‘Disney’s not-so-magic new kingdom’, Business Week Online. Emmons, N. (2001) ‘Disney tradition to carry on at Hong Kong park’, Amusement Business, Vol. 113, No. 3, p. 1. Fong, A. (1995) ‘Points: the future looks bright for China and Hong Kong’, Columbia Journal of Business, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 61–62. Fowler, G.A. and Marr, M. (2005) ‘Disney’s China play’, Wall Street Journal (Eastern Edition), Vol. 245, No. 117, pp. B1–B7. Ho, D. (2006) ‘Hong Kong Disneyland—it’s a small world’, <http://www.brandchannel.com/features_profile.asp ?pr_id=269>, accessed 20 April 2007. Hobson, J.S.P. (1994) ‘Feng shui: its impacts on the Asian hospitality industry’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 6, No. 6, pp. 21–26. Holson, L.M. (2005) ‘Disney bows to feng shui’, International Herald Tribune Business, <http://www. iht.com/articles/2005/04/24/business/disney.php>, accessed 25 April 2007. ‘Hong Kong Disneyland: the Magic Kingdom meets the Middle Kingdom’, <http://www.china-connections. net/Articles/1ed/DisneylandHK.htm>, accessed 27 April 2007. Landreth, J. (2005) ‘Mouse meets Mao’, Amusement Business, Vol. 117, No. 9. Lee, M. (2005) ‘East meets west: Hong Kong park is a classic Disney with an Asian accent’, USA Today, <http://www.usatoday.com/travel/destinations/200507-07-hong-kong-disney_x.htm>, accessed 25 April 2007. Miller, P.M. (2007) ‘Disneyland in Hong Kong’, China Business Review, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 31–33. Rossbach, S. (1984) Feng Shui, Rider, London. ‘The horns of a dilemma’ (1992) Economist, Vol. 325, No. 7787, p. 80. Yardley, J. (2006) ‘Numbers game in China’, International Herald Tribune: Asia-Pacific, <http://www.iht.com/ articles/2006/07/04/news/plates.php>, accessed 25 April 2007. Questions 1 Discuss the elements of culture that have been addressed in this case study. 2 What did Disney learn from its mistakes in Paris? 3 How did Disney embrace Chinese culture with its Hong Kong venture? 4 What cultural issues would arise if Disney chose Dubai for its next theme park? Photo credit Hong Kong Disneyland © Kim Morgan.