Individual Differences in Leadership Derailment

advertisement

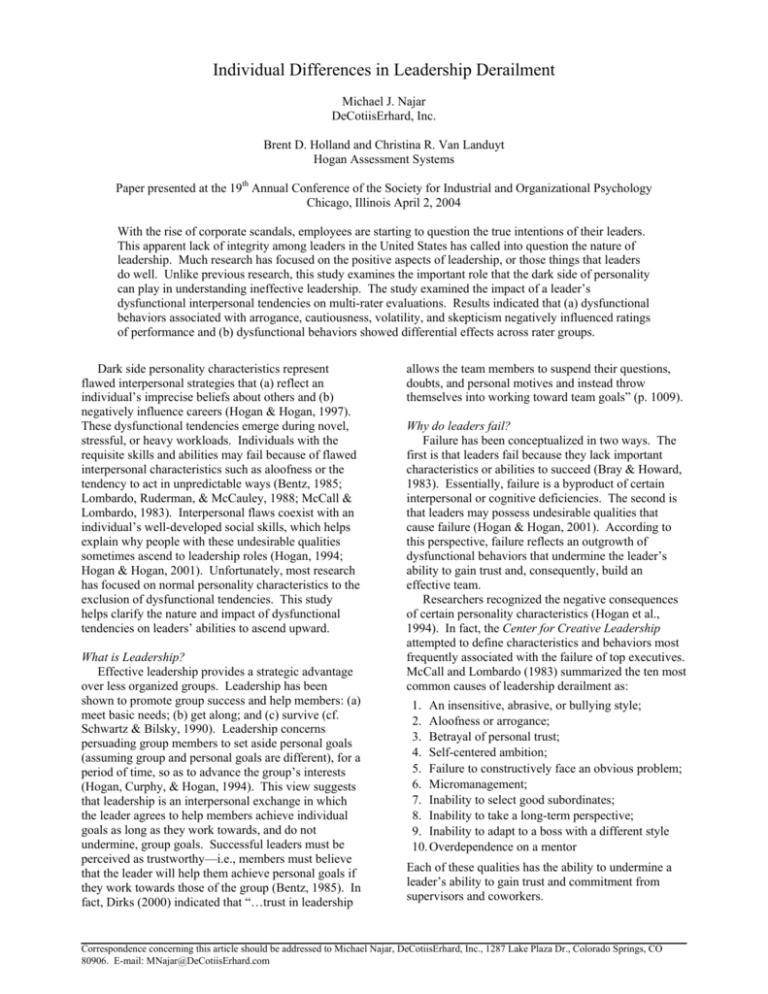

Individual Differences in Leadership Derailment Michael J. Najar DeCotiisErhard, Inc. Brent D. Holland and Christina R. Van Landuyt Hogan Assessment Systems Paper presented at the 19th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Chicago, Illinois April 2, 2004 With the rise of corporate scandals, employees are starting to question the true intentions of their leaders. This apparent lack of integrity among leaders in the United States has called into question the nature of leadership. Much research has focused on the positive aspects of leadership, or those things that leaders do well. Unlike previous research, this study examines the important role that the dark side of personality can play in understanding ineffective leadership. The study examined the impact of a leader’s dysfunctional interpersonal tendencies on multi-rater evaluations. Results indicated that (a) dysfunctional behaviors associated with arrogance, cautiousness, volatility, and skepticism negatively influenced ratings of performance and (b) dysfunctional behaviors showed differential effects across rater groups. Dark side personality characteristics represent flawed interpersonal strategies that (a) reflect an individual’s imprecise beliefs about others and (b) negatively influence careers (Hogan & Hogan, 1997). These dysfunctional tendencies emerge during novel, stressful, or heavy workloads. Individuals with the requisite skills and abilities may fail because of flawed interpersonal characteristics such as aloofness or the tendency to act in unpredictable ways (Bentz, 1985; Lombardo, Ruderman, & McCauley, 1988; McCall & Lombardo, 1983). Interpersonal flaws coexist with an individual’s well-developed social skills, which helps explain why people with these undesirable qualities sometimes ascend to leadership roles (Hogan, 1994; Hogan & Hogan, 2001). Unfortunately, most research has focused on normal personality characteristics to the exclusion of dysfunctional tendencies. This study helps clarify the nature and impact of dysfunctional tendencies on leaders’ abilities to ascend upward. What is Leadership? Effective leadership provides a strategic advantage over less organized groups. Leadership has been shown to promote group success and help members: (a) meet basic needs; (b) get along; and (c) survive (cf. Schwartz & Bilsky, 1990). Leadership concerns persuading group members to set aside personal goals (assuming group and personal goals are different), for a period of time, so as to advance the group’s interests (Hogan, Curphy, & Hogan, 1994). This view suggests that leadership is an interpersonal exchange in which the leader agrees to help members achieve individual goals as long as they work towards, and do not undermine, group goals. Successful leaders must be perceived as trustworthy—i.e., members must believe that the leader will help them achieve personal goals if they work towards those of the group (Bentz, 1985). In fact, Dirks (2000) indicated that “…trust in leadership allows the team members to suspend their questions, doubts, and personal motives and instead throw themselves into working toward team goals” (p. 1009). Why do leaders fail? Failure has been conceptualized in two ways. The first is that leaders fail because they lack important characteristics or abilities to succeed (Bray & Howard, 1983). Essentially, failure is a byproduct of certain interpersonal or cognitive deficiencies. The second is that leaders may possess undesirable qualities that cause failure (Hogan & Hogan, 2001). According to this perspective, failure reflects an outgrowth of dysfunctional behaviors that undermine the leader’s ability to gain trust and, consequently, build an effective team. Researchers recognized the negative consequences of certain personality characteristics (Hogan et al., 1994). In fact, the Center for Creative Leadership attempted to define characteristics and behaviors most frequently associated with the failure of top executives. McCall and Lombardo (1983) summarized the ten most common causes of leadership derailment as: 1. An insensitive, abrasive, or bullying style; 2. Aloofness or arrogance; 3. Betrayal of personal trust; 4. Self-centered ambition; 5. Failure to constructively face an obvious problem; 6. Micromanagement; 7. Inability to select good subordinates; 8. Inability to take a long-term perspective; 9. Inability to adapt to a boss with a different style 10. Overdependence on a mentor Each of these qualities has the ability to undermine a leader’s ability to gain trust and commitment from supervisors and coworkers. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Michael Najar, DeCotiisErhard, Inc., 1287 Lake Plaza Dr., Colorado Springs, CO 80906. E-mail: MNajar@DeCotiisErhard.com LEADERSHIP DERAILMENT Why multi-source feedback? One way to understand whether a leader is succeeding is perceptions of his or her performance. Multi-source feedback allows us to understand perceptions of performance from the perspectives of different organizational members. By examining performance from different perspectives, it may be possible to clarify our understanding of how a leader interacts with different people. Multi-source feedback reflects the process of gathering performance-related feedback from multiple constituencies within an organization (e.g., supervisor, peer, and subordinates), and is a useful tool to evaluate leadership (Bracken & Timmreck, 2001). The rationale for using multi-source feedback is that performance varies from time-to-time and different raters have unique opportunities to observe these onthe-job behaviors (Day, 2000). Therefore, it is essential to obtain feedback from a variety of sources to create a more accurate picture of a leader’s performance. Leaders are traditionally evaluated by their supervisor(s). One problem with this approach is that even poor leaders realize the significance behind maintaining healthy relationships with their bosses (Hogan, 1994). Moreover, supervisors do not always have the opportunity to see leaders’ everyday or typical behaviors. Consequently, supervisor ratings may not reflect those typical behaviors that may cause derailment. An equally important source of performance information is a leader’s peers. Peers have more opportunities to observe everyday behavior than supervisors do, and most leaders may be less guarded in the company of equals. Thus, peers should have more opportunities to accurately rate potentially derailing characteristics. Hypotheses The derailment literature (McCall & Lombardo, 1983; Bentz, 1985; Leslie & Van Velsor, 1996) suggests that failure can be classified into themes, each of which is associated with the possession of dark side tendencies. As indicated above, some of these tendencies will be more visible to a leader’s peers, as opposed to the leader’s supervisor. First, failure is usually associated with an individual’s inability to build interpersonal relationships effectively. Leaders who seem arrogant are less likely to build effective working relationships with their peers. After all, arrogant individuals tend to be described as egocentric, unwilling to listen, and stubborn. Moreover, given that a leader’s success depends upon effective team building, these individuals are clearly disadvantaged (Bentz, 1985; Lombardo et al., 1988; and McCall & Lombardo, 1983). Further, it is likely that leaders will engage in self-protective behavior where arrogance is concerned; that is, overt arrogance toward one’s supervisor is likely to result in negative consequences. Therefore, a leader’s peers, not his or her supervisor, will be better equipped to evaluate everyday relationship building. Hypothesis 1: Characteristics associated with arrogance will lead to lower performance ratings by peers. Second, some individuals fear being criticized or blamed and, consequently, they refuse to take risks. These people remain vigilant against making embarrassing errors, sometimes avoiding decisionmaking altogether, or deferring to their supervisor. At work, they may seem cautious, pessimistic, and avoid accepting responsibility (Fico, Hogan, & Hogan, 2000). Their unwillingness to take initiative or accept accountability may decrease their value to the work group and/or organization. Therefore, it seems plausible to assume that a leader’s unwillingness to make decisions should be noticed by supervisors and peers. Hypothesis 2: Characteristics associated with cautiousness will lead to lower performance ratings by both supervisors and peers. Next, excitable individuals are difficult to please and typically expect to be disappointed, criticized, or treated unfairly. Their perceptions of being unfairly treated generally result in emotional outbursts. Because of their emotional instability, these leaders have trouble getting along with others—peers and supervisors. Most of the time, coworkers will describe these individuals as impatient, moody, negative, and somewhat volatile (Fico et al., 2000). Emotional outbursts will be more difficult to hide, and therefore, will be seen by both supervisors and peers. Hypothesis 3: Characteristics associated with excitability will lead to lower performance ratings by supervisors and peers. Finally, in order to lead, one must be followed. We have argued that leadership involves the ability to persuade others to set aside personal agendas, at least a short period of time, for the good of the group. Convincing others to set aside their individual goals requires a great deal of trust. Leaders who seem untrustworthy are less likely to gain others’ support. Therefore, we expect that leaders who seem cynical and distrustful will be more likely to receive lower performance ratings from peers, but not necessarily supervisors because the leader is not trying to get the supervisor to set aside his/her personal goals. Hypothesis 4: Characteristics associated with skepticism and distrust will lead to lower performance ratings by peers. 2 NAJAR, HOLLAND, AND VAN LANDUYT Method Subjects The sample included high-potential senior executives (N = 295) at a Fortune 500 company who completed an assessment battery as part of an organizational development project. The sample was composed primarily of white (63.30%) males (69.90%). Measures Personality Measure. The Hogan Development Survey (HDS: Hogan & Hogan, 1997) is a 168 item paper-and-pencil assessment. The HDS assesses eleven patterns of interpersonal behavior (dark side) that are most apparent during times of stress and heavy workloads. These behaviors may impede the development of strong working relationships with others, hinder productivity, or limit overall career potential (see Table 1). HDS scales measure a variety of potentially dysfunctional behaviors. The scales of primary interest in the present research include: (a) Bold – measures tendency to be arrogant and unwilling to admit 3 mistakes, (b) Cautious – measures resistance to taking even calculated risks (c) Excitable – measures tendency to be moody and inconsistent and (d) Skeptical – measures tendency to be cynical, distrustful, and questioning of others. The HDS Manual contains reliability and validity data that define the measure’s psychometric and predictive characteristics. The HDS scales show construct validity in terms of both test-test relations and test-non-test relations. The average internal reliability coefficient across HDS scales is .67, and test-retest reliability coefficients average .75. Criterion Measure. The organization provided multi-rater performance data. The multi-rater tool consisted of 54 items measuring four leadership factors (Business, Results, People, and Self) and 11 interpersonal factors (see Table 2). Raters included (a) Manager – the candidate’s immediate supervisor; and (b) Others – a composite group of peers and other individuals who have observed the candidate’s job performance. Note that we have also presented an aggregated rater variable, which is the average score on each performance dimension across raters. Table 1. Hogan Development Survey Scales and Definitions HDS Scale Definition The degree to which a person seems… Excitable moody and inconsistent, being enthusiastic about new persons or projects and then becoming disappointed with them. Skeptical cynical, distrustful, overly sensitive to criticism, and questioning others’ true intentions. Cautious resistant to change and reluctant to take even reasonable chances for fear of being evaluated negatively. Reserved socially withdrawn and lacking interest in or awareness of the feelings of others. Leisurely autonomous, indifferent to other people’s requests, and becoming irritable when they persist. Bold unusually self-confident and, as a result, unwilling to admit mistakes or listen to advice, and unable to learn from experience. Mischievous to enjoy taking risks and testing the limits. Colorful expressive, dramatic, and wanting to be noticed. Imaginative to act and think in creative and sometimes unusual ways. Diligent careful, precise, and critical of the performance of others. Dutiful eager to please, reliant on others for support, and reluctant to take independent action. LEADERSHIP DERAILMENT 4 Table 2. Performance Dimensions and Definitions Crit. Dimension Definition Resilient Manages stress easily and in a mature manner. Trusting Listens to others and avoids questioning their motives. Adaptable Displays willingness to change or take calculated risks. Communicative Communicates openly with staff and monitors staff morale. Cooperative Completes tasks in a timely manner and avoids procrastinating. Fair-Minded Shows respect to coworkers and shares credit for accomplishments. Dependable Follows through on commitments and operates with a sense of integrity. Modest Acts with humility and remains focused on team, rather than personal, goals. Judgment Makes good decisions based on the best available information. Empowering Delegates projects to others and ensures priorities are established. Independent Begins and finishes work in the absence of direct supervision. Business Leadership Ability to think strategically and generate well conceived solutions. Results Leadership Ability to take initiative and achieve results. People Leadership Ability to work well with others and build a high-performing team. Self Leadership Ability to act with maturity, be accountable, and cope well with stress. Results Descriptive Statistics. As shown in Table 3, HDS mean scores ranged from 39.52 (Leisurely) to 63.16 (Diligent) and standard deviations ranged between 25.19 (Skeptical) and 27.99 (Bold). Inter-scale correlations were moderate, with coefficients between r = -.15 (Colorful and Reserved) and r = .47 (Colorful and Bold). Descriptive statistics for the aggregated (average of Manager and Others’ ratings) criterion rating dimensions appear in Table 4. Average scores ranged between 3.94 (Trusting) and 4.52 (Self Leadership), with standard deviations between .30 (Dependable and Self Leadership) and .44 (Trusting). Alpha coefficients were within acceptable limits and range .73 (Modest) and .90 (Self Leadership). The inter-correlations of criterion dimensions were between .40 (Independent and Fair-Minded) and .85 (Modest and Fair-Minded; Results and Communicative; and People Leadership and Business Leadership). Table 3. Hogan Development Survey Descriptive Statistics HDS Scale Ske Cau HDS Scales Res Lei M SD Exc Excitable 51.97 26.51 -- Skeptical 55.50 25.19 .34 -- Cautious 46.56 25.35 .33 .19 -- Reserved 48.38 27.00 .30 .24 .36 -- Leisurely 39.52 27.23 .15 .25 .29 .09 -- Bold 60.90 27.99 .15 .42 -.01 .09 .23 Bol Mis Col Ima Dil -- Mischievous 56.54 25.98 .15 .37 .01 .06 .22 .40 -- Colorful 54.78 25.81 -.03 .19 -.22 -.15 .12 .47 .41 -- Imaginative 56.32 25.52 .14 .27 .03 .06 .13 .37 .33 .32 -- Diligent 63.16 26.49 .09 .02 .05 -.03 .17 .13 -.02 .06 -.01 -- Dutiful 48.08 26.74 -.01 -.11 .17 -.16 .00 -.02 -.07 .07 .07 .16 Note. N = 295. Correlation coefficients at or above r = .11 are significant at p < .05. Dut -- NAJAR, HOLLAND, AND VAN LANDUYT 5 Table 4. Criterion Rating Dimensions Descriptive Statistics Across Raters Criterion Dimension Crit. Dimension M SD Res Tru Ada Com Coo Fai Dep Mod Jud Emp Ind Bus Res Peo Sel Resilient Trusting Adaptable Communicative Cooperative Fair-Minded Dependable Modest Judgment Empowering Independent Business Lead. Results Lead. People Lead. Self Lead. .92 .71 .78 .81 .80 .82 .73 .89 .77 .71 .80 .68 .90 4.27 3.94 4.43 4.34 4.36 4.34 4.43 4.29 4.43 4.23 4.38 4.36 4.25 4.35 4.52 .40 .44 .37 .39 .36 .43 .30 .37 .37 .32 .36 .34 .35 .37 .30 .82 .64 .67 .65 .65 .58 .70 .65 .69 .61 .66 .71 .75 .71 .73 .85 .46 .60 .55 .74 .60 .70 .49 .48 .42 .52 .63 .44 .61 .89 .63 .64 .43 .67 .56 .70 .61 .76 .79 .70 .74 .67 .85 .71 .73 .73 .72 .71 .63 .63 .70 .85 .66 .69 .79 .62 .81 .73 .72 .67 .66 .76 .74 .82 .69 .88 .65 .85 .55 .51 .40 .52 .71 .45 .68 .80 .77 .78 .69 .71 .80 .78 .82 .79 .73 .65 .59 .56 .67 .75 .65 .75 .76 .67 .75 .69 .73 .60 .87 .81 .85 .76 .91 .78 .80 .89 .74 Note. N = 295. All correlation coefficients are significant p < .05. Alpha coefficients appear in diagonal (bold). Table 5 presents managerial ratings possessing average scores from 3.27 (Resilient) to 4.60 (Dependable) and standard deviations between .43 (Resilient) and .62 (Adaptable). Finally, Others’ ratings corresponded closely to those of the Manager with average scores between 3.15 (Resilient) and 4.36 (Dependable) and standard deviations ranging from .35 (Resilient) to .56 (Empowering) (see Table 6). Table 6 also shows scale inter-correlations ranging from .56 (Empowering and Trusting) to .89 (People Leadership and Business Leadership and People Leadership and Results Leadership). Table 5. Criterion Rating Dimensions Descriptive Statistics from the Manager’s Perspective Criterion Dimension Crit. Dimension M SD Res Tru Ada Com Coo Fai Dep Mod Jud Emp Ind Bus Res Peo Sel Resilient Trusting Adaptable Communicative Cooperative Fair-Minded Dependable Modest Judgment Empowering Independent Business Lead. Results Lead. People Lead. Self Lead. .78 .76 .75 .78 .74 .87 3.27 4.16 4.29 4.43 4.41 4.51 4.60 4.40 4.50 4.38 4.38 4.38 4.40 4.33 4.59 .43 .57 .62 .54 .57 .54 .48 .52 .55 .58 .55 .53 .58 .51 .48 .55 .61 .67 .61 .61 .52 .64 .55 .59 .53 .58 .60 .67 .64 .64 .66 .66 .65 .55 .64 .62 .66 .55 .51 .56 .60 .65 .58 .63 .72 .70 .71 .51 .65 .59 .69 .68 .69 .73 .71 .71 .69 .73 .70 .65 .71 .69 .67 .64 .67 .75 .76 .72 .73 .77 .60 .68 .60 .73 .76 .71 .77 .75 .77 .75 .75 .71 .76 .59 .54 .49 .58 .61 .57 .68 .68 .68 .68 .63 .65 .68 .71 .73 .80 .73 .63 .60 .59 .64 .67 .62 .68 .81 .81 .75 .76 .77 .81 .76 Note. N = 295. All correlation coefficients are significant p < .05. Alpha coefficients appear in diagonal (bold). .81 .78 .78 .75 .78 .73 .82 .81 .82 .79 .85 .82 .81 .86 .83 LEADERSHIP DERAILMENT 6 Table 6. Criterion Rating Dimensions Descriptive Statistics from Others’ Perspective Criterion Dimension Crit. Dimension M SD Res Tru Ada Com Coo Fai Dep Mod Jud Resilient 3.15 .35 .58 Trusting 3.87 .55 .76 .82 Adaptable 4.12 .47 .75 .75 .75 Communicative 4.17 .51 .69 .71 .80 .81 Cooperative 4.13 .53 .70 .66 .76 .79 .78 Fair-Minded 4.22 .49 .71 .72 .71 .71 .76 .79 Dependable 4.36 .49 .77 .75 .74 .80 .79 .82 Emp Ind Bus Res Peo Sel .83 Modest 4.12 .46 .68 .71 .67 .69 .67 .84 .77 .82 Judgment 4.28 .50 .72 .65 .77 .78 .82 .72 .80 .69 .90 Empowering 4.17 .56 .63 .59 .73 .74 .80 .66 .67 .61 .80 .87 Independent 4.10 .48 .66 .60 .73 .76 .73 .64 .67 .64 .76 .81 .75 Business Lead. 4.19 .49 .67 .62 .79 .79 .81 .67 .73 .62 .85 .82 .81 .88 Results Lead. 4.19 .51 .78 .71 .81 .84 .83 .75 .84 .75 .86 .79 .79 .85 .91 People Lead. 4.13 .49 .73 .66 .79 .81 .85 .70 .80 .68 .88 .84 .81 .89 .89 .90 Self Lead. 4.30 .47 .77 .69 .79 .77 .82 .74 .82 .73 .85 .79 .78 .83 .86 .88 Note. N = 295. All correlation coefficients are significant p < .05. Alpha coefficients appear in diagonal (bold). Table 7 presents correlations between HDS scales and criterion dimensions by rater. Across scales and perspectives, the Excitable, Imaginative, Skeptical, and Cautious scales yielded the most consistent validity coefficients, whereas the Reserved and Dutiful scales showed the weakest validities. Overall, correlations ranged from r = .15 (Diligent and Fair-Minded, Manager) to r = -.28 (Excitable and Resilient, Aggregate; Cautious and Independent, Aggregate). We expected tendencies associated with arrogance to negatively predict Others’ performance ratings. Results indicated that the Bold scale negatively predicted performance ratings from the Others’ perspective, but not the Aggregate or Managerial ratings. The validity coefficients between Bold and Others’ ratings ranged from -.01 (Independent) to -.20 (Trusting). The results provided some support for Hypothesis 1. According to Hypothesis 2, we anticipated that leaders who seem risk averse would receive poorer performance ratings across Manager and Others’ perspectives. The results provided some support for this hypothesis. The Cautious scale was correlated with the Aggregated criteria (r = -.06 to r = -.28). Interestingly, the Cautious scale correlated with only five scales across the Managerial ratings (r = .01 to r = -.15), whereas Cautious predicted 12 criterion dimensions across the Others’ ratings (r = -.08 to r = .21). Volatility showed the strongest relation with job performance ratings across perspectives. The Excitable scale predicted all 15 criterion dimensions across Aggregated ratings (r = -.13 to r = -.28), and Others’ ratings (r = -.15 to r = -.26), and fourteen dimensions across Managerial ratings (r = -.10 to r = -.22). These results provide support for Hypothesis 3. Trust is the key to effective leadership. Leaders who lack the ability to gain others’ trust will inevitably fail. Results provided support for Hypothesis 4, which stated that leaders who seem cynical and distrustful would receive lower performance ratings from Others. Consistent with expectations, the HDS Skeptical scaled predicted fourteen criterion dimensions across Others’ ratings (r = -.08 to r = -.21). In addition, the Skeptical scale only predicted five dimensions across Manager’s ratings (r = .01 to r = -.15). Discussion The main purpose of the study was to help understand the relation between dysfunctional tendencies and multi-rater performance evaluations. The study found distinct differences between peer and supervisor ratings. Data indicate that leaders have a propensity to modify their interpersonal style depending on the group with whom the leader is interacting. .88 NAJAR, HOLLAND, AND VAN LANDUYT 7 Table 7. Hogan Development Survey Correlates with Criterion Ratings by Rater Perspective Criterion Dimension HDS Scale Res Tru Ada Com Coo Fai Dep Mod Jud Emp Ind Bus Res Peo Sel Excitable Manager Other -.28* -.18* -.22* -.16* -.14* -.17* -.20* -.17* -.19* -.13* -.20* -.20* -.24* -.15* -.16* -.19* -.18* -.20* -.10 -.18* -.16* -.17* -.19* -.16* -.19* -.18* -.22* -.21* -.25* -.21* -.16* -.21* -.25* -.17* -.22* -.15* -.20* -.22* -.26* -.21* -.23* -.16* -.22* -.22* -.18* Skeptical Manager Other -.15* -.12* -.09 -.12* -.10 -.09 -.14* -.11 -.10 -.00 -.10 -.13* -.18* -.06 -.04 -.06 -.07 -.06 .01 -.11 -.01 -.15* -.06 -.13* -.14* -.15* -.21* -.21* -.19* -.15* -.17* -.15* -.18* -.16* -.18* -.13* -.08 -.16* -.20* -.14* -.18* -.14* -.15* -.17* -.19* Cautious Manager Other -.23* -.10 -.25* -.20* -.06 -.09 .01 -.14* -.11 -.05 -.16* -.19* -.14* -.24* -.09 -.08 .01 -.10 -.14* -.07 -.08 -.03 -.13* -.08 -.20* -.17* -.12* -.08 -.17* -.15* Reserved Manager Other -.08 -.03 -.04 -.11 -.06 -.04 -.02 -.09 .01 Leisurely Manager Other -.13* -.06 -.10 -.05 -.09 -.11 Bold Manager Other -.08 -.10 -.02 -.03 .05 -.04 .02 -.06 -.14* -.20* -.18* -.10 .01 -.05 -.10 -.02 -.02 -.01 -.06 -.06 -.07 -.05 -.12* -.11 -.06 -.07 -.10 Mischievous Manager Other -.16* -.15* -.11 -.12* -.17* -.17* -.22* -.17* -.12* -.08 -.06 -.07 .00 .02 -.09 -.06 -.06 -.08 -.10 -.07 -.10 -.16* -.17* -.09 -.14* -.13* -.18* -.12* -.13* -.10 -.07 -.07 -.04 -.13* -.14* -.09 -.05 -.13* -.12* -.15* -.17* -.09 -.08 -.11 -.14* Colorful Manager Other -.06 .02 -.08 -.00 -.03 .00 -.04 .02 -.07 -.02 .02 -.07 Imaginative Manager Other -.17* -.14* -.11 -.13* -.21* -.17* -.19* -.17* -.14* -.10 -.11 -.17* -.15* -.15* -.15* -.15* -.19* -.20* -.16* -.15* -.16* -.20* -.20* -.16* -.21* -.23* -.11 -.13 -.13* -.05 -.10 -.14* -.12* -.07 -.07 -.08 -.01 -.09 -.03 Diligent Manager Other Dutiful Manager Other .13* .13* .11 -.03 -.02 -.01 -.07 -.07 -.06 -.06 -.09 -.03 -.07 -.06 -.04 -.19* -.07 -.06 -.06 -.15* -.08 -.12* -.01 -.13* -.13* -.10 -.05 -.12* .03 -.05 -.06 .03 .07 -.13* -.14* -.05 .03 .01 .07 -.01 -.02 .01 .11* .01 .10 -.00 .09 .08 .03 -.02 .12* .02 -.07 -.03 .02 .03 -.04 -.05 -.08 -.14 -.09 -.06 -.07 -.05 -.01 -.02 -.10 -.06 -.04 -.03 -.14* -.08 .16* -.03 .14* .15* .14* .05 .11 .09 .07 .10 .03 .00 .07 .03 .08 .07 .04 .04 .07 .05 .04 .05 .10 .04 .02 .03 .05 -.03 -.03 .03 -.02 .01 .00 -.04 -.03 .02 -.05 -.03 -.03 -.17* -.09 -.14* -.07 -.19* -.17* -.17* -.13* -.13* -.20* -.17* -.15* -.18* -.21* -.20* -.05 -.09 -.08 -.10 -.12* -.14* -.06 -.07 -.02 -.01 -.03 -.03 -.14* -.19* -.10 -.08 -.03 -.10 -.19* -.21* -.28* -.23* -.20* -.11 -.13* -.15* -.15* -.08 -.12* -.18* -.21* -.16* -.16* .02 -.08 -.06 -.01 -.01 -.03 -.03 .02 -.10 .07 .03 .13* -.09 .09 .10 -.06 -.08 .01 .00 .02 -.04 .11 .08 .06 -.05 -.03 -.02 .14* .13* .12* -.02 .02 .01 -.01 .01 -.02 -.09 -.08 .00 -.09 -.03 -.01 -.17* -.20* -.21* -.14* -.17* -.15* -.11 -.05 -.14* -.02 .04 -.08 -.14* -.13* -.22* -.17* -.07 -.05 .15* .11 .11 .08 .07 .13* .12* .09 .08 .04 .03 .05 .04 .02 .02 .06 .03 .03 Note. N = 295. * p < .05. First row reflects aggregated performance ratings – i.e., average of Manager and Other ratings. As expected, leaders with the tendency to seem overly self-confident or arrogant received lower performance ratings from peers, but not supervisors. Results indicating that peers are more observant of these arrogant tendencies are important. A leader has a vested interest in maintaining a collegial relationship with his/her supervisor. When interacting with others, however, leaders may be more likely to resist feedback and act competitively (McCall & Lombardo, 1983). The consequence is that others may negatively evaluate these tendencies; the performance ratings support this position. The long-term implication of these arrogant tendencies remains to be seen, but it is likely that leaders who show these tendencies will eventually struggle to build a team of committed individuals, which may eventually derail those leaders’ careers (Hogan et al., 1994). Leaders must make decisions, but some leaders tend to be more risk averse than others. We expected riskaverse leaders to receive lower performance ratings across Manager and Others’ perspectives. Although results provided some support for the hypothesis, Others’ tended to observe the risk avoidant tendencies more so than the Manager. These findings lead to two conclusions: (a) the most effective leaders do indeed take some calculated chances and (b) cautious leaders LEADERSHIP DERAILMENT tend to mask this tendency from their Manager more than with Others in the organization. On one hand, leaders may recognize the potentially negative consequences of seeming risk averse in the eyes of their supervisor. Therefore, the leader tries to seem open to new ideas and risks. On the other hand, leaders seem more willing to show their cautious side in the presence of Others. Perhaps leaders are less guarded in the company of peers and other organizational members who have little or no direct supervisory responsibility over the leader. Leaders who receive the poorest performance ratings across perspectives tend to behave in emotionally unpredictable ways. The close correspondence suggests that leaders who act with volatility tend to be less able to control the impressions they make on people within the organization, regardless of whether the person is a supervisor or peer. Unlike characteristics associated with arrogance or cautiousness, emotional outbursts tend to be more publicly visible and may tend to carry a stronger negative valence than other derailing behaviors. This may help explain why these behaviors correlate with nearly all performance criteria across perspectives. Research has shown that trust is an integral part of a leader’s ability to lead. If a leader is unable to establish trust with Others, he or she will be more likely to receive poorer performance ratings. Once again, the leader’s ability to manage impressions seems to be an important finding. Leaders seem skilled at projecting trust in the presence of the Manager, but Others are likely to detect distrustfulness or cynicism in a leader. Therefore, leaders who seem distrustful will most likely struggle to gain commitment from coworkers, and an inability to gain commitment may ultimately result in failure. Another noteworthy finding is that leaders tend to be passively resistant with their Manager (Leisurely), but more direct with their peers (Mischievous). Obviously, this finding requires more in-depth research, but the implication is interesting. This result suggests that leaders tend to show mild types of contentious behavior in different forms to different audiences. Leaders may understand the career limiting potential of acting too combative with their Supervisor, so the leader enacts retribution in more passive ways. Conversely, leaders may feel more confident confronting issues directly with Others. Limitations This study has three primary limitations. First, performance ratings are only one of a myriad of criteria that could be used in evaluating leadership effectiveness. Objective indices of financial performance would be helpful in determining the overall effectiveness of a leader. Second, the lack of previous research on derailing tendencies limited our ability to draw complex, theoretical hypotheses. That is, our theories do not help us understand the role of characteristics that promote derailment. Future Directions Although not hypothesized, some other relations emerged from this study (as shown previously in Table 7). First, the Leisurely scale, which concerns seeming stubborn and passively resistant, was related to Managerial ratings, and to a lesser degree, Others’ ratings. Second, the Mischievous scale, which looks at an individual’s desire to test limits, correlated with Others’ ratings but did not correlate with Managers’ ratings. Finally, the Imaginative scale, which is associated with acting in creative or unusual ways, showed strong relations with Managerial ratings, but only weak relations with Others’ ratings. Future research should examine these relationships further. Continuing research should also focus on creating theoretical accounts of leadership that will help us understand the implications of trust and derailment. In addition, it would be beneficial to establish one definition of leadership; a team-based approach seems to be the most promising (Hogan et al., 1994). Finally, it would be beneficial to look at derailing characteristics across organizations and managerial levels. This study helps clarify the relationship between dark side personality characteristics and leadership ratings. The results highlight the importance of evaluating dark side characteristics from multiple perspectives. More importantly, the study reinforces the need to evaluate a leader’s ability through multiple perspectives. Others seem better equipped to evaluate non-emotive forms of leader behaviors, whereas Managers and Others seem equally well equipped to evaluate on-the-job emotional behavior. Unlike previous research on leadership, this study demonstrates empirically the important role that dark side personality scales can play in understanding the nature of leadership. References Bentz, V. (1985). A view from the top: A thirty year perspective of research devoted to the discovery, description, and prediction of executive behavior. Paper presented at the 92nd Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles, August. Bracken, D. W., & Timmreck, C. (2001) (Eds.). The Handbook of Multisource Feedback: The Comprehensive Resource for Designing and Implementing MFS Processes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Bray, D. & Howard, A. (1983). The AT&T longitudinal study of managers. In K. W. Schaie (ed.), Longitudinal Studies of Adult Psychological Development (pp. 112-146). New York: Guilford. 8 NAJAR, HOLLAND, AND VAN LANDUYT Fico, J. M., Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (2000). Interpersonal Compass Manual and Interpretation Guide. Tulsa: Hogan Assessment Systems. Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: A review in context. The Leadership Quarterly, 11, 581-614. Dirks, K. T. (2000). Trust in leadership and team performance: Evidence from NCAA basketball. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 1004-1012. Hogan, R. (1994). Trouble at the top: Causes and consequences of managerial incompetence. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice & Research. 46, 9-15. Hogan, R., Curphy, G. J., & Hogan, J. (1994). What we know about leadership: Effectiveness and personality. American Psychologist, 49, 493-504. Hogan, R. & Hogan, J. (1997). Hogan Developmental Survey Manual. Tulsa: Hogan Assessment Systems. Hogan, R., & Hogan, J. (2001). Assessing leadership: A view from the dark side. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9, 40-51. Leslie, J. & Van Velsor, E. (1996). A look at derailment today: North America and Europe. Greensboro: Center for Creative Leadership. Lombardo, M. M., Ruderman, M. N., & McCauley, C. D. (1988). Explanations of success and derailment in upper-level management positions. Journal of Business and Psychology, 2, 199-216. McCall, M. & Lombardo, M. (1983). Off the track: Why and how successful executives get derailed (Tech. Rep. No. 21). Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a theory of the universal content and structure of values extensions and cross-cultural replications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 878-891. 9