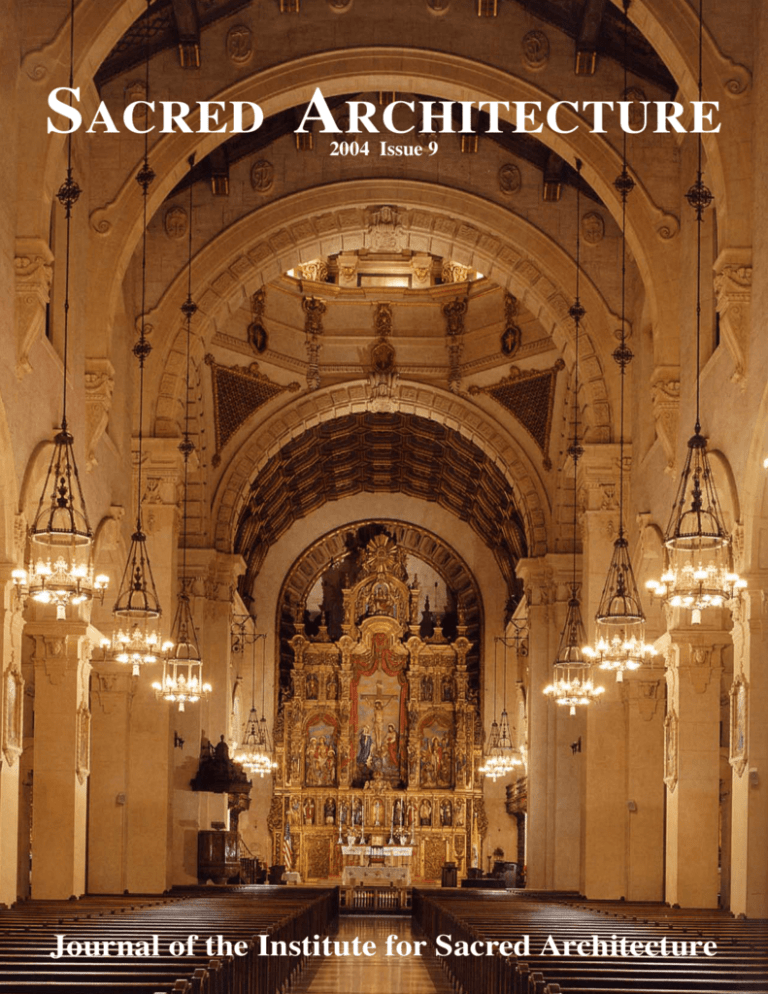

Sacred Architecture Journal: Patronage & Design in Churches

advertisement