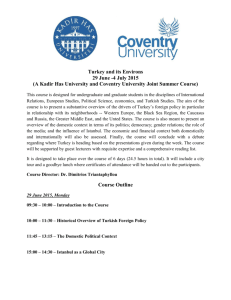

Turkish Foreign Policy in the Twenty

advertisement