Working Capital Management Model in value chains

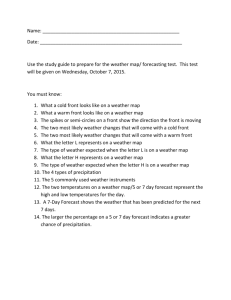

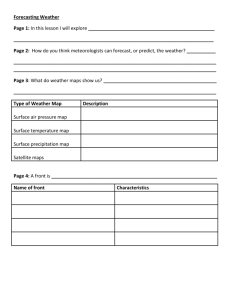

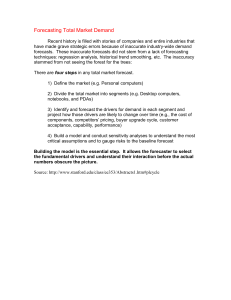

advertisement