Understanding Attrition from French Immersion Programs

advertisement

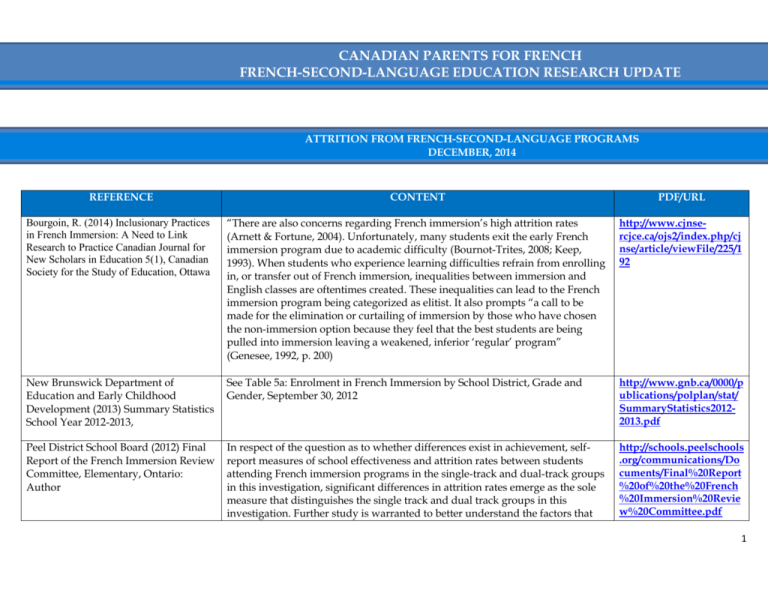

CANADIAN PARENTS FOR FRENCH FRENCH-SECOND-LANGUAGE EDUCATION RESEARCH UPDATE ATTRITION FROM FRENCH-SECOND-LANGUAGE PROGRAMS DECEMBER, 2014 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL Bourgoin, R. (2014) Inclusionary Practices in French Immersion: A Need to Link Research to Practice Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education 5(1), Canadian Society for the Study of Education, Ottawa “There are also concerns regarding French immersion’s high attrition rates (Arnett & Fortune, 2004). Unfortunately, many students exit the early French immersion program due to academic difficulty (Bournot-Trites, 2008; Keep, 1993). When students who experience learning difficulties refrain from enrolling in, or transfer out of French immersion, inequalities between immersion and English classes are oftentimes created. These inequalities can lead to the French immersion program being categorized as elitist. It also prompts “a call to be made for the elimination or curtailing of immersion by those who have chosen the non-immersion option because they feel that the best students are being pulled into immersion leaving a weakened, inferior ‘regular’ program” (Genesee, 1992, p. 200) http://www.cjnsercjce.ca/ojs2/index.php/cj nse/article/viewFile/225/1 92 New Brunswick Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (2013) Summary Statistics School Year 2012-2013, See Table 5a: Enrolment in French Immersion by School District, Grade and Gender, September 30, 2012 http://www.gnb.ca/0000/p ublications/polplan/stat/ SummaryStatistics20122013.pdf Peel District School Board (2012) Final Report of the French Immersion Review Committee, Elementary, Ontario: Author In respect of the question as to whether differences exist in achievement, selfreport measures of school effectiveness and attrition rates between students attending French immersion programs in the single-track and dual-track groups in this investigation, significant differences in attrition rates emerge as the sole measure that distinguishes the single track and dual track groups in this investigation. Further study is warranted to better understand the factors that http://schools.peelschools .org/communications/Do cuments/Final%20Report %20of%20the%20French %20Immersion%20Revie w%20Committee.pdf 1 REFERENCE School District No. 19 (2013) Early French Immersion Update, Revelstoke: BC CONTENT PDF/URL contribute to this finding. There is not an identifiable tool in place within the board that will allow for conducting exit surveys for students who leave the program to help administrators better understand why students are leaving. All French Immersion and Francophone programs face attrition. With only two entry points and many potential points of departure, this is simply inevitable. The following table details the grade by-grade average attrition rates for BC French Immersion programs http://www.sd19.bc.ca/pd f%20Files%20for%20Web site/March%202013%20E FI%20Update.pdf French Immersion Secondary Attrition - 1999-2004 (Percentage) Source Canadian Parents for French - BC & Yukon Branch Grade 8 12.4 Grade 9 12.1 Grade 10 13.4 Grade 11 14 Grade 12 12 While BC's attrition rate is not bad comparatively, secondary attrition is a serious problem for French Immersion programs. On average only 55% of Grade 7 FI students get their Bilingual Dogwood. 35% of students leave in either Grade 10, 11 or 12. While these students have benefited substantially from French Immersion and may well be functionally bilingual, the loss in learning momentum is considerable. Halifax Regional School Board (2011) The Delivery of French Immersion, Halifax: Author See Table 7. History of the system-wide Early Immersion attrition rates by grade for the past five years. Two particular columns of data require attention because they contain an attrition rate which is obviously higher than the others in the column. The Grade 7 attrition rate in 2006-07 is 16.9%, much greater than the other four rates for that Grade. Although no explanation for this deviation could be found, the rates for the previous two years can be included in a revised calculation. If the attrition rates (10.8% and 9.9%) for Grade 7 in the two years prior to 2006-07 are included in calculating the average, it becomes 9.4% instead of 8.9%. Similarly, the attrition rate for Grade 11 in 2010-11 is an extreme deviation from the others in the same column. If it is excluded from the calculation, the 4-year average is 3.8% instead of 9.2%.Generally, the data in Table 7 show that EI attrition rates for Grade 1 and Grade 2 are higher than those for Grade 5 and 6 and they gradually improve from Grade 2 to Grade 6. Then the data show another peak from Grade 6 to Grade 7 when most of the students move to another school. The attrition rates for both Early Immersion and Late http://www.hrsb.ca/sites/ default/files/hrsb/Downl oads/pdf/reports/20102011/March/FrenchImmersion-Study.pdf 2 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL Immersion (Table 7 and Table 8) show a peak from Grade 9 to Grade 10. School District No. 68 (2011) French Immersion Program Review School District No. 68 (Nanaimo-Ladysmith) British Columbia: Author Durant, M. (2010) Developing a Knowledge-Based Research Approach to Second Language Learning, PCH Second Language Learning Research Roundtable Includes comparison of French Immersion attrition in similar sized school districts http://www.sd68.bc.ca/D ocuments/FrenchImmersi onReviewNov302011.pdf According to the Centre for Education Statistics, fewer than 50% of Québec francophones agreed that their elementary and secondary L2 education was adequate. Over half of the young people living in a majority situation want to learn the other language. The extra-curricular activities suggested were: classes, lessons, courses, tutoring, and language exchanges. The most popular reasons for the lack of L2 learning were related to personal interest and opportunities to practice the target language. Employment opportunities were the main reason for interest. Exchanges through Young Canada Works official language programs have had positive effects including more L2 use at home. XXXXXXXXX Sinay, E. (2010) Programs of Choice in The TDSB: Characteristics of Students in French Immersion, Alternative Schools, and Other Specialized Schools and Programs, Toronto District School Board, Toronto See: Figure 1: Percentage of Students Enrolled in French Immersion Programs by Gender and Percentage of All French Immersion Students in the TDSB Over Time http://www.tdsb.on.ca/Po rtals/0/community/comm unity%20advisory%20co mmittees/fslac/support% 20staff/programsofchoice studentcharacteristics.pd f Boudreaux, N., Olivier, D. (2009) Student Attrition in Foreign Language Immersion Programs, Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Louisiana Education Research Association Lafayette, March 5-6, 2009, Louisiana: Author This article reviews the literature pertaining to student attrition at all levels in foreign language immersion settings. Boudreaux summarizes the research done in the field pointing out the key points from studies conducted in the past for reasons why students have left foreign language looking at different subgroups of students and the reasons for their exit. After her review of the literature she offers a few suggestions for further study. She says that more research be done in the united states to examine the problem from and American perspective, as well as looking at reasons why parents enroll their children and then withdraw them from the foreign language immersion schools. ] CASLT undertook a study to review and summarize existing knowledge about the various modes of delivering core French. The pedagogical focus within core http://ullresearch.pbwork s.com/f/Boudreaux_ULL_ StudentAttritioninForeig nLanguagePrograms.pdf Mady, C. (2008) The Relative Effectiveness of Different Core French http://www.caslt.org/pdf/ EffectiveDeliveryModels 3 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL Delivery Models-Review of the Research, Panorama, Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers, CASLT Research Series, Ottawa French programs is to be considered as well as access to these programs. It was confirmed more time is needed and that provincially and territorially mandated and scheduling difficulties time is affecting the lack of speaking skills, in addition to. According to the students, there needs to be less of a focus on linguistic aspects and more opportunities to interact with francophones. A number of pedagogical changes are being reviewed in various curricula to provide core French oral communication opportunities. These opportunities are closely geared to student interests and needs, such as the drama for learning approach that they enjoyed and viewed as important. Non-semestered core French programs at the secondary level are being reviewed to improve time on task. Eight provinces are promoting distance education courses to ensure accessibility to French learning. CoreFrench_Engl.pdf Statistics Canada (2008) French Immersion: 30 Years Later, Ottawa: Author While the proportion of girls and of boys in non-immersion programs is roughly equal in all provinces, girls account for 3 of 5 students in French immersion programs in all provinces except Quebec http://www.statcan.gc.ca/ pub/81-004x/200406/6923-eng.htm Cadez, R.V. (2006) Student Attrition in Specialized High School Programs: An Examination of Three French Immersion Centres Student attrition has always been a problem for French immersion programs, especially at the high school level. In response to a lack of current research, this study seeks to discover if the problem persists. It also examines how today's French immersion high schools are dealing with other problem areas identified in research done in the past. These areas include, among others, students' learning challenges, behavioural challenges, and difficulties with the French language. The study documents the attrition rates from 1990 to 2004 in three high schools in Manitoba that are French immersion centres. In an effort to understand why students remained or left the immersion programs, 35 teachers, 220 current students, and 18 former students who have left the program to attend English schools were surveyed. All three sample groups' perceptions of the program show that while many things that were considered problematic in the literature are no longer a concern, other issues continue to persist. Furthermore, the data show that male and female students tend to leave the French immersion program for different reasons. However, the common motive that instigates the decision to leave appears to be the perception that higher grades can be achieved in an English school. https://www.uleth.ca/dsp ace/handle/10133/340 Scroll down to ‘Files in this item’ for link to PDF 4 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL Joseph, D. (2006) Le français…il y en a toujours qui choisissent de l’étudier, Réflexions Vol 25, #1, Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers, Ottawa, ON Vol 25, #1 This article studies why students choose to stay in FSL programs, and gives hints as to how parents and teachers can help encourage students to remain in FSL programming. Based on a survey that the author administered, the following reasons reveal why Grade 11 and 12 students have remained in French programs: job preparation, French certificate, parents, teachers, national cohesion, and friends. The article elaborates on the role that parents and teachers play in the motivation of the students to continue learning French. http://www.caslt.org/wha t-we-do/publicationsreflexions_en.php Scroll down to #25 Kissau, S. (2006) Gender Differences in Motivation to Learn French, Canadian Modern Language Review 62(3), University of Toronto Press, Ontario This study examines the reasons why males a less motivated to learn French in a school. The study found that roughly 25% of the students were continuing in French in grade 10, and that of that number 70% were female compared to 30% male. The study found that the best predictor between male and female was their desire to learn French (females expressing more of a desire to do so). The study found that females’ main reason to learn French was to be able to communicate in French; so as to be able to experience French culture and meet French people, whereas boys felt that learning French was not worth their time and that they were not interested in experiencing French culture. The study also concluded that a higher percentage of males compared to females perceived their success in French as “luck”. The author finishes his study by saying that learning French is still perceived as being feminine by a large number of the population. In conclusion the author offers a number of recommendations to improve the perception of French as a second language learning amongst males. Firstly, he recommends that more male oriented topics be discussed in school. Secondly, he suggests that males be exposed to more men who have pursued careers in languages. Finally, he recommends that males be shown possible career paths that exist with languages. http://utpjournals.metapr ess.com/content/1w7138w q70k76004/?p=ddd835d12 c794af5be1c6c6c61e464ee &pi=2 Turnbull, M., Hart, D., Lapkin, S. (2006) Grade 6 French Immersion Students' Performance on Large-Scale Reading, Writing, and Mathematics Tests: Building Explanations, The Alberta Journal of Educational Research Vol. XLIX, No. 1, Spring 2003, 6-23, Alberta “… an important finding of the EQAO testing program has been of systematic differences in the performance of boys and girls, favoring the latter. Given that girls are frequently overrepresented in immersion, it is worth considering possible the effects of sex. In fact the overrepresentation of girls among immersion students is virtually identical at grades 3 and 6. Girls account for 57% of grade 3 immersion students, compared with 48% of regular program students. At grade 6 the proportions are 56% and 49% respectively. Thus any changes in relative test performance cannot be ascribed to an increasing "feminization" of immersion between grades 3 and 6. http://ajer.journalhosting .ucalgary.ca/index.php/aj er/article/view/354/346 5 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL In the case of reading and writing, the effects of sex and program appear to be additive. Girls do better than boys in each program, and immersion students do better than regular program students across both sexes. In the case of mathematics, sex effects virtually disappear. Immersion students do better than regular program students, but boys and girls perform similarly in each program.” Arnett, K., Fortune, T. (2004) Strategies for Helping Underperforming Immersion Learners Succeed , ACIE Newsletter #7 http://www.carla.umn.ed This article explains some useful approaches to make French Immersion (FI) u/immersion/acie/vol7/br more inclusive, specifically for those who do not excel academically or have idge-7(3).pdf learning disabilities. In 1991, Stern claimed that transfer rates from FI to nonimmersion programs of K-6 students in Canada were 40-50%. Keep (1993) assessed 37 immersion students who successfully completed 10 years in the program and compared them to 34 others who had transferred before grade six and 54 students from grades 1-6 who were still in the program. Twice as many of the transfers were from male students who were 1-2 years below grade level. 85% of them had cognitive processing weaknesses with regards to memory, language, and visual perception. Arnett suggests strategies for perception (input), processing (deciphering/organizing) and expression (output) for listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Some of these strategies include providing additional time, graphic representations of concepts, presenting the same information using different modalities, presenting mnemonic devices, accepting multiple forms of expressing info, and asking global comprehension questions. Canadian Parents for French (2005), The State of French-Second-Language Education in Canada, Ottawa: Author Canadian Parents for French (2005), The State of French-Second-Language Education in Canada, Ottawa: Author Prairie Research Associates Inc. (2000) French Immersion: Findings of School Administrator Focus Groups, Winnipeg: Author. Includes survey findings from study of 400 university students with and without elementary/secondary core and/or immersion programs http://cpf.ca/en/files/FSL2005-EN.pdf The whole reports addresses core French issues, including attrition http://cpf.ca/en/files/FSL2004-EN.pdf The Bureau de l’éducation française, Manitoba Department of Education and Training commissioned this qualitative report which summarizes the opinions of the 25 principals/vice-principals of dual track schools and FI centres who participated in the focus groups. On-going challenges include: creating a French environment within their schools, defending the FI program to other teachers and superintendents, as well as keeping satisfied parents informed and http://www.edu.gov.mb.c a/k12/docs/french_imm/fi ndings_focus.pdf 6 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL involved. Long-term challenges include: maintaining student numbers, offering a varied curriculum in French, and finding qualified FI teachers. The principals noted that, while there may be individuals and specific groups within school and divisions playing a leadership role, there is no province-wide leadership and they call for the Bureau de l’éducation française to fill this void. Cummings, J. (2000) Immersion Education for the Millennium: What We Have Learned from 30 Years of Research on Second Language Immersion, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto Press, Toronto Cummins introduces the three kinds of immersion: early, middle, and late. There are many dropouts from immersion before the end of elementary school; however, many students do not continue FI in high school. According to Cummins, these students have a difference between receptive and expressive skills due to a lack of contact with native target language speakers. He believes that these dropout rates are due to the lack of opportunities to use oral or written French for creative and problem solving activities in these transmission-oriented classrooms. The author discusses how the immersion programs are beneficial because bilingual children have greater sensitivity to linguistic meanings and are more flexible in thinking then monolingual children. His language interdependence theory discusses how language skills can transfer, especially when the languages are not similar. In order to improve immersion programs, Cummins believes that cooperative activities are necessary. This is seen as a risk by many educators, since they are afraid the students will feel free to use their L1. Comprehensible input must extend into critical literacy writing activities to develop language awareness. http://www.carla.umn.ed u/cobaltt/modules/strateg ies/CUMMINS/cummins. pdf Obadia,A., Theriault, C. (1997) Attrition in French immersion programs: Possible solutions, Canadian Modern Language Review 53(3) University of Toronto Press, Toronto Studies the perceptions of French coordinators, helping teachers, school principals, and French immersion teachers in British Columbia school districts regarding the Frenhc immersion attrition rate and students' reasons for leaving the program. The research differed from previous studies in that it also investigated the strategies used by administrators and teacher to reduce attrition. Over two-thirds of French coordinators responding felt the dropout rate was normal. Elementary school principals felt students were more likely to drop out in seventh grade early immersion than late immersion, and secondary school principals felt students were more likely to drop out in eighth grade. There was little consensus among the teachers. Overall, data suggest that junior high school is a critical period for retention. All groups felt academic difficulty, limited choice of subjects, and peer pressure were the most common reasons for leaving immersion. Some districts had participated in research on French http://files.eric.ed.gov/ful ltext/ED400674.pdf 7 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL immersion attrition; most of the coordinators and some principals and teachers mentioned some form of action to reduce attrition. Suggestions for intervention to reduce attrition fell into three categories: district, school, and classroom. A list of suggestions to reduce the drop-out rate in French Immersion Programs is provided. Ellsworth, C. (1997) A study of factors affecting attrition in late French immersion This study attempted to identify the reasons behind student attrition in late French immersion. It also examined the individual characteristics and situational factors associated with student withdrawals (gender, points in the school year associated with higher levels of attrition, age, and number of years since withdrawal from LFI) in order to find commonalities and patterns relating to attrition. a written questionnaire was given to 73 students who had transferred out of the LFI program in one Newfoundland & Labrador school board between 1986 and 1996. The study suggested that student withdrawal resulted primarily from concerns about academic achievement and the challenging nature of the LFI program. Findings also showed that a strong, dynamic relationship existed between the abovementioned situational factors and attrition. Indications showed that grade 7 students had the greatest risk for early withdrawalfrom LFI. Furthermore, students tended to leave at year end, rather than mid-semester. Additionally, males often had more negative perceptions of LFI, but were not found to drop out in greater numbers than females. Recommendations; 1. That School Boards support teacher efforts to establish contact between LFI students and French speaking peoples –possibly achieved through travel, guest speakers, teleconferences or the internet. 2. That guidelines be established for working with students who wish to transfer to the English stream. 3. That students who wish to transfer to the English stream be interviewed and required to complete a follow-up questionnaire. 4. That records be kept on attrition in LFI, including student reasons and counsellor perceived reasons why students transfer to the English stream. 5. That parents be informed of strategies for helping their child in LFI with homework. 6. That a teacher assistant be utilized, especially in grade 7 where students are more at risk of dropping out. 7. That programs for providing remedial assistance to students in LFI be explored. This may be achieved, for instance, through establishing phone help http://research.library.mu n.ca/5038/1/Ellsworth_Co rinneC.pdf 8 REFERENCE CONTENT PDF/URL lines, creating peer tutoring programs, and by involving teacher assistants. Hart, D., Lapkin, S. , Howard, J. (1994) Attrition from French Immersion Programs in a Northern Ontario City: 'Push' and 'Pull' Factors in Two Area Boards, Modern Language Centre, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education; Toronto This article identifies factors associated with voluntary attrition from French immersion at the transition point between elementary and secondary school and throughout secondary school. Student characteristics and attitudes associated with 'stayers', 'debaters', and 'leavers'. Reasons for learning French, concerns about marks, levels of social support, and self-assessments of achievement were all found to be common factors in two boards in the students' decisions to stay in or leave immersion. [0080] http://books.google.ca/bo oks/about/Attrition_from _French_Immersion_Pro grams.html?id=6ptINQA ACAAJ&redir_esc=y 9