396

Int. J. Business Performance Management, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2011

How does business performance measurement

perform? An empirical study with reference to

leading companies in India

Keyur Thaker

Indian Institute of Management Indore,

Rau Pithampur Road, Pigdember,

Indore, M P 453 331, India

E-mail: thakerkeyur@yahoo.com

E-mail: keyurt@iimidr.ac.in

Abstract: With increased adoption and resource spent for business

performance management, it is interesting to inquire about its practice and

performance. Based on the response from CFO’s of the 38 leading Indian

companies, we found that BPM is satisfying tactical purposes well, but lagged

in strategic, top management and learning and development needs. The results

compare well with Tonge et al. (2000), Malcolm (2006), Wiersma (2009), etc.

When compared with Simmons (1995b) levers of control, we observe better

performance on diagnosis and belief control system, while lagged as interactive

control tool. Despite increasing use and importance of various non-financial

measures, we observed lower satisfaction with its measurement quality and

fewer linked those measures to compensation, comparable with Lingle and

Schiemann (1996). Our findings are symptomatic of evolution of BPM

to overcome the inadequacies of reliance on accounting-based performance

measurement (RAPM) to strategic management system and more recently

management learning and development tool.

Keywords: business performance measurement; BPM; functions; purpose;

performance; CFO; leading companies; India; practice; strategic management

systems; management learning and development; Simmons levers of control;

management control research framework.

Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Thaker, K. (2011)

‘How does business performance measurement perform? An empirical study

with reference to leading companies in India’, Int. J. Business Performance

Management, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp.396–416.

Biographical notes: Keyur Thaker is an Assistant Professor and the Area

Chair of Finance and Accounting at Indian Institute of Management Indore. His

research, teaching and consulting interest includes corporate finance, cost and

management accounting, management control systems, corporate performance

management, project finance and structuring, investments and valuation.

He has been active in conducting corporate training and consulting in

the area of his interest. He has several publication and presentations in

international conferences and refereed international and national journals. Of

late, he is inquisitive about and propagating consciousness in business for

competitiveness and making the world better place to live. He aspires to work

on implementing consciousness in business organisation and its implication on

performance management and control system.

Copyright © 2011 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd.

How does business performance measurement perform?

1

397

Introduction

Business performance measurement (BPM) is an organisational approach to assess

and monitor performance in relation to set of goals and objectives. It encompasses

methodologies, frameworks and indicators that are used to help organisation in

the formulation and assessment of strategy, motivate people and to communicate or

report performance (Marr, 2009). Performance measurement systems play key role in

developing strategic plans, evaluating the achievement of organisational objectives, and

compensating managers (Jean-Francois, 2006). Yet, many managers feel that traditional

accounting-based measurement systems no longer adequately fulfil these functions

(Ittner and Larcker, 1998). The perceived inadequacies of the control systems

reliance on accounting-based performance measures (RAPM) have motivated a variety of

performance measurement innovations ranging from ‘improved’ financial metrics such

as ‘economic value’ measures to ‘balanced scorecards’ of integrated financial and

non-financial measures to measures of intellectual capital and measures for discloser and

reporting (Ittner and Larcker, 1998; Verbeeten, 2005; Thaker, 2005, 2010; Chenhall and

Langfield-Smith, 2007; Meyer, 2007). Moreover, with great interest in performance

measurement with many companies attempting to implement the balanced scorecard,

there is also evidence that many of these implementations are not successful (Bourne

et al., 2003a, 2003b). However, despite increasing adoption of these performance

measurement innovations, very few studies have examined the new measures’ economic

relevance, the implementation issues arising from their adoption, or the performance,

their use and its efficacy in satisfying intended purposes (Kellen, 2003). A major research

motivated to study the practices and state of affairs to address many such issues with

reference to companies in India was conducted, part of which is discussed in the paper.

2

Literature review

“The fields of performance measurement and management control have changed

dramatically in recent years to adopt to the changing paradigms and environment of

business” (Neely, 2002). Industry has recognised the importance of the implementation

and coordination of strategy with organisational structure, management systems, and

managerial behaviour. There has been increased adoption and almost 2/3rd of the

large corporate have adopted a formal performance measurement system like balance

scorecard (Kaplan and Norton, 1992). Surveys indicate that 85% of the organisation

will have performance measurement initiatives underway (Rigby, 2001). Performance

measurement and the balanced scorecard are widely used in Europe and US but limited

in Asia. However, there is growing anecdotal evidence that the topic is taking of there

(in Asia) as well (Neely et al., 1995; Neely, 2005). Bourne et al. (1999) iterate the need

for further research into the issues related to implementation of performance measures.

He further states that performance measurement literature is at the stage of identifying

difficulties and pitfalls to be avoided based on practitioner experience with few published

research studies (Bourne et al., 2003a, 2003b). Nevertheless, managers and researchers

alike are attempting to find better ways to link performance metric to strategy through

systems like balanced scorecard and shareholder value analysis to drive improved

corporate performance (Epstein and Manzoni, 2003).

398

K. Thaker

The early studies on performance measurement stated the purposes as to facilitate

management control and strategy implementation (Koontz, 1959; Anthony, 1965).

According to Thakur et al. (2001), it is the managerial process for measuring progress

towards planned performance and when required taking corrective action. He further

stated that control fulfils a number of organisational purposes. First, control helps to

merge short range and long range plans into a state of greater consistency, second, control

helps bring consistency to the activities and accomplishment throughout the organisation

in ends-means manner, i.e., the final outcome of one work unit becomes the means or

inputs by which the next work unit begins. Third, control can help bring individual

behaviours in one with organisational goals by monitoring absenteeism, work hours and

performance. As suggested by Bititci et al. (2002), the BPM has a variety uses and lists

the following reasons:

1

to monitor and control

2

to drive improvement

3

to maximise the effective ness of the improvement effort

4

to achieve alignment with organisational goals and objectives

5

to reward and to discipline.

Simons (2000) stated that performance measurement is the tool for balancing five

major tensions within a firm. Balancing those tensions leads to effective strategy

implementation and achievement of planned performance: balancing profit, growth

and control; balancing short-term results against long-term capabilities and growth

opportunities; balancing performance expectation of different constituencies; balancing

opportunities and attention; and balancing the motive of human behaviour. Thus, the core

idea for the control framework is to balance needs for innovation and constraints through

levers of control. In his earlier seminal work, Simmons (1995a, 1995b) uses the metaphor

of four levers of control. Namely, diagnostic, interactive, belief and boundary control

systems. These four control levers are nested as they are working simultaneously even

through for different purpose. Beliefs systems are used to enhance core values related to

business strategy and to inspire search for new opportunities while boundary systems

reduce risk by setting limits to strategically undesirable behaviours. Through diagnostic

control system critical success factors are communicated and motivated and finally

interactive control systems are used to discuss strategic uncertainties to learn novel

strategic response to changing environment. Reilly and Rambhala’s (2001) thesis brought

out benefits of possessing a state-of-the-art performance measurement system in a

business organisation such as, the availability of timely performance feedback and

alignment of business activities toward common goals. Insights into the big-picture

relevance of each person’s job, etc. are just a few of the obvious benefits of using an

effective performance measurement system. Similarly, Campbell et al. (2002) report that

performance measurement data can be used to test the effectiveness of organisational

strategies. The benefits as suggested by Reilly and Rambhala (2001), to the managers

were listed further as value-based thinking; focus on stakeholder deliverables, value

paths, i.e., linking processes and activities to value creation, shared corporate strategy,

process improvement opportunities, individual management development, etc. Of course

the expectation from new set of performance measurement system at early stage of its

How does business performance measurement perform?

399

introduction was to over come the limitations of traditional financial measures, but

recently performance measures are increasingly recognised to support managers and the

organisation as they seek and clarify strategy, communicate strategy and challenge the

assumption (Neely et al., 2000; Kaplan and Norton, 1996, 2001; Neely and Al Najjar,

2006; Meyer, 2007). Marr and Schiuma (2003) identified three primary drivers for

organisation to measure performance, namely implementation of strategy, influencing

people’s behaviour and external validation of performance. Otley (2002) stated that BPM

have three main purposes from finance functional perspective. Namely:

1

financial measures of performance as tools of financial management (as tool for

functional manager for management of the finance function)

2

financial performance as major objective of business organisation and finance

function as well

3

financial measures of performance as mechanism for motivation and control within

the organisation.

Malcolm (2006) views performance measures from two perspectives. The first

perspective on resource focus deals with the four principal resource areas, namely

physical, human, information and financial. Second, level focus, relates to three levels,

operational (task specific), organisational (functional, business units, and responsibility

centre wise) and strategic control. The control process has following steps:

1

establishing performance standards

2

measuring the performance

3

comparing performance

4

evaluating performance and taking action.

The action taken can be altering standards, continuing operations and/or correcting

deviations. Attempts are also made to explore the functions and benefits such measures

could provide and how well are those functions fulfilled. Franco-Santos et al. (2007)

reviewed 17 different definitions of BPM and argued that only necessary role is the use

of BPM systems it to measure performance. Further, they propose five different

categories of BPM systems role:

1

measure performance

2

strategy management

3

communication

4

influencing behaviour

5

learning and improvement.

A seminal study by Neely and Al Najjar (2006) brought long awaited support to the

thesis that management learning and not management control is the true role of

performance measurement by longitudinal study of British Airway. They further

400

K. Thaker

proposed that performance measures can be used to challenge the assumptions that

manager’s hold about how the business operates. It is a powerful technique to facilitate

strategy mapping. A stream of research recognised the importance of resources

perspective (Malcolm, 2006) in form of intangibles and focused on its measurement.

Through systematic literature review, Marr et al. (2003) explored the motives for which

firms measure their intellectual capital. They identified the following reasons:

1

to help organisations formulate their strategy

2

assess strategy execution

3

assist in diversification and expansion decisions

4

use these as a basis for compensation

5

to communicate measures to external stakeholders.

Comparably, a more recent argument as an out come of a survey by Marr (2009) states

that the performance measures are used as a tool to measure the readiness of intangible

value drivers. The primary purpose of performance measurement as found by

Marr are, controlling, strategy planning, everyday decision-making, strategy validation,

communication, motivation and reward, managing relationship with stakeholders,

regulatory reporting and compliance. Wiersma (2009) found that management uses BSC

for decision-making and decision-rationalising, coordination and self-monitoring with

reference to 19 Dutch firms. Based on 17 case studies in Finnish firms, Malmi (2001)

found two different types of BPM (BSC) usage. Some firms use the scorecard as

management by objective systems while other firms used the BSC as information system

to provide mangers a tool to improve performance. Speckbacher et al. (2003) survey of

42 firms using performance measures (BSC) in three different ways/types. Type 1 as a

specific approach to measure intangibles, where intangibles are identified and measured

by non-financial strategic measures rather then by their financial value. Type 2 as a

multidimensional performance measurement system and describe strategy by using a

cause and effect logic to link tangible and intangible assets. And type 3, which is type 2,

plus implementing the strategy by defining objectives, action plans and results and

linking incentives to business performance measures. This classification is analogous to

the successive evolution of balanced scorecard from a basic tool to balance the financial

and non-financial measures to a strategic management system and more recent advocacy

as learning and development tool. Thus, the purpose of BPM have evolved and morphed

from inadequacy of reliance on accounting-based performance measurement to

measurement tool that balanced various perspectives to strategic change framework and

more recently for management learning and development tool.

Performance measures and its management come as a handy tool in achieving

planned performance and the views on use of BPM converge across various studies. We

propose to build on Otley’s (2002) argument to suitably adopt following functions to

apply to a border perspective, i.e., the entire organisational or business performance.

1

Performance measures as tools for management of business: Here, the focus is on

how efficient and effective use of recourses the management does to achieve the

wider aims of the organisation. As per Malcolm (2006) here, the focus is on resource

and performance thereof in managing the resources at the disposal of management.

How does business performance measurement perform?

401

2

Performance measures as a major objective of a business organisation: In empirical

studies and literature, it is argued that the most organisation have a financial goal as

a major objective. Finance literature for long supported wealth maximisation as

organisational objective, and evolved in defining the measure from net profit, cash

profit to market value added or economic profit, etc. The objectives can be

non-financial as well. Like customer satisfaction, market share, innovation and

product leadership, social responsibility and so on. The performance measures are

manifestation of goals, objectives, targets and KRAs and are used as diagnostic

control (Simons, 2000) tools.

3

Performance measures as a mechanism for motivation and control within the

organisation. Performance measures as management control tool (Malcolm, 2006;

Simons, 2000). Here, the performance measures can be used in various management

control activities like planning, budgeting, performance evaluation, reward and

compensations with aim to induce goal congruent behaviour amongst the managers.

Simons’ (2000) belief control systems closely relates to this.

4

Performance measure as tool for strategy formulation and implementation. The

chosen strategy defines critical success factors and performances (measures),

which become focal points for design and operation of the control system (Kaplan

and Norton, 2006) or say Malcolm (2006) level focus. Thus, aids the strategy

implementation (Campbell et al., 2002) by providing the performance information

provides as the basis for thinking about new strategies and management learning as

argued by Neely and Al Najjar (2006), which is called interactive control (Simmons,

1995a, 1995b).1

The above purpose category was extensively communicated to CFO’s during the in

person interviews with the researcher and found to have good acceptance. At the same

time, the above categorisation manifests substantial convergence and overlap amongst the

views about purpose of performance across the stream of literature.

Wm. Schiemann and Associates surveyed 203 executives in 1996 on the quality, uses

and perceived importance of various financial and non-financial performance measures

(Lingle and Schiemann, 1996). Their results are presented in Table 1. While 82% of the

respondents valued financial information highly, more than 90% clearly defined financial

measures in each performance area, included these measures in regular management

reviews, and linked compensation to financial performance. In contrast, 85% valued

customer satisfaction information highly, but only 76% included satisfaction measures

in management reviews, just 48% clearly defined customer satisfaction for each

performance area or used these measures for driving organisational change, and only

37% linked compensation to customer satisfaction. Similar disparities exist for measures

of operating efficiency, employee performance, community and environment, and

innovation and change. More importantly, most executives had little confidence in any of

their measures, with only 61% willing to bet their jobs on the quality of their financial

performance information only 41% on the quality of operating efficiency indicators, the

highest rated non-financial measure. This clearly poses obvious question. How are BPM

performing? A replica of this study was performed in India and the results are produced

in the later part of this paper.

402

K. Thaker

Table 1

Companies’ use and opinion about measurement practice

Percentage of respondents’ practices using/favourable

Measure of

Highly

valued

information

Quality of

information

Clear

measures

Measures

regularly

updated

Linked to

compensation

Financial

performance

82%

61%

92%

88%

94%

Operating efficiency

79

41

68

69

54

Customer satisfaction

85

29

48

48

37

Employee

performance

67

16

17

27

20

Innovation/change

52

16

13

23

12

Source: Lingle and Scheimann (1996)

One can observe wide comparability and agreement on use or purpose of performance

measurement across various contributions. On a more philosophical note I would propose

the role of BPM is to illuminate mangers thinking and understanding about business

strategy and performance so that right decision are made, inspire and charge them to

strive to further strategic goals and integrate people and parts of the organisation

(coordinate and unite efforts) towards strategy so the organisations thrives and sustains.

Thus, BPM have three roles, to illuminate, inspire and integrate, people and parts of the

organisation to the rightful goals and purposes.

However, the larger question is, are the performance measurement systems truly

performing? The key questions as described by Jean-Francois (2006) are: Does the

organisation maximise the potential of its performance measurement system? How can

one improve the system? Does exploiting the full potential of the system make

difference? Jean deployed a national survey of manufacturing firms with an objective to

provide a better understanding of how the top management teams of manufacturing firms

could use performance systems to improve strategic management and organisational

performance. He further stated that if PMS is periodically reviewed, it could contribute to

the improvement of organisational performance. Implementing systems is only the first

step – having them reach the full potential (performing to the best) is the real challenge.

And therefore as iterated by Neely (2005) that one of dominant themes for future set of

research in BPM would to know performance of BPM and barriers to it is

Implementation. Similarly, Tuomela (2005), states that several field studies imply that in

examining the relationship between strategy and management accounting system

(including PMS), it might be more relevant to investigate how those systems are used

rather then whether these systems are used. Therefore, it makes sense to investigate

empirically how well BPM is performing across various functions and sort out difference

in the performance of BPM across various purposes groups or objectives it is being used.

2.1 Objective and rational

For crystallising and conceptualising for this research, purpose of BPM can be

summarised under following major categories.

How does business performance measurement perform?

403

1

BPM as measurement tool for management

2

BPM as measurement tool

3

BPM manifests major objective of a business

4

BPM as a mechanism for motivation and control

5

BPM as tool for decision-making and strategy formulation

6

BPM as tool to communicate and implement strategy (strategic management system)

7

BPM as a management learning and development tool.

The above classification built on various contributions discussed in literature can be

related with the Simmons (1995b) levers of control. For instance, the items # 2 and 4 to a

great extent reflects what Simmons calls the diagnostic control, items 3, 4 and 6 relates

well belief and boundary control, items 5 and 7 reflects the interactive control. The

linkages across those function categories with the four levers should not be interpreted in

watertight and strict manner but they surely to a higher extent on the continuum reflects

the linkage discussed.

The theoretical work leads to formation of following hypothesis.

•

First: There is no significant difference in performance across different functions of

BPM.

•

Second: There is no significant difference in performance across various groups

(function category) of BPM.

The second hypothesis can be further elaborated by restating that the objective is to

explore and support or refute the theory about weather difference in performance of BPM

across various purpose category exist and to extrapolate on the state of affairs in terms of

extent of the maturity in the use of BPM.

3

Methodology

A structured survey instrument was developed based on the inferences from Otley

(1999), Chenhall (2003) and Ferreira and Otley’s (2009) analysis framework for study

of performance measurement system and management control systems. The first of the

instrument contained set of questions that solicited response for objectives, strategies,

organisation structure and KRA and was useful to set the context and relevant thinking

for respondent CFO. The later part contained various items on Likert scale on different

aspects of BPM purpose and practice. Final part solicited the details of responded and

key financials of the company. Tonge et al. (2000) have used similar scale for BPM

practice study in the UK was used. A pilot survey drew response from three CFO to

check the validity of the questions, after which the instrument was suitably revised and

finalised. Initially telephonic contact was made to the CFO or his deputy to brief about

research and solicit the response. A questionnaire was e-mailed with a covering note

requesting response to CFO’s of companies from BS 2002 list. The list contained the

largest 200 companies in India. The companies in financial sector were excluded. Follow

up through e-mails; referrals and phone calls were done. As the response rate was low, it

404

K. Thaker

was decided to seek appointment for in person interaction with CFOs. Referrals of CFO’s

who responded earlier proved to be a good means to increase the response rate. The

response to personal interview was very encouraging with CFO’s spending about 90

minutes to as much as 210 minutes for response. Valuable insights were drawn during the

extended discussion beyond merely filling the questionnaire. As a consequence, we had

usable response through personal visits to CFO’s of 38 leading companies in India. The

earlier studies by Tonge et al. (2000) had 41 responses, Malmi (2001) study had response

from 17 firms, Speckbacher (2003) 42 firms and more recent study by Wiersma (2009)

19 firms. The companies responded for this study included leading and large companies

in information technology consulting, consumer goods (durable and non-durable), metal,

healthcare and pharmaceutical, automobiles, petrochemicals, hotels and hospitality, etc.

Nine of those companies were part of the Benchmark stock market index BSE 30 and

constituted over 46% weightage of the index (2005). Given their size and diversity of the

sample as suggested by Govindrajan and Gupta (1985) there is no prima-facie reason to

expect systematic bias in the findings. Moreover, the respondents were CFO’s themselves

who would be largely involved in championing the performance management and control

in the organisations they work for. In the main, studies that have examined relatively

large organisations, usually justifying this, as it is large firms that tend to adopt the type

of practices incorporated within more formal management control systems (Chenhall,

2003). Moreover, Khandwalla (1972, 1977) found that large firms were more diversified

in product lines, employed mass production techniques, were more divisionalised and

made greater use of sophisticated controls and therefore provide a good opportunity and

is relevant (Merchant, 1981) for the management control research. Consequently,

empirical studies like Govindrajan and Gupta (1985), Tonge et al. (2000) have studied

large (Fortune 100, FTSE 100) companies.

Descriptive statistics were applied for analysis. To find the averages, the weights for

all the scales were given in the order of 1 to 5. For example, strongly satisfied was

assigned weight of 1 while strongly dissatisfied was assigned weight of 5. Kruskal Wallis

ANOVA test was performed. The KW test is a non-parametric version of one-way

ANOVA. The assumption behind this test is that the measurements come from a

continuous distribution, but not necessarily a normal distribution (Hollander and Wolfe,

1973). The test is based on an analysis of variance using the ranks of the data values, not

the data values. Output includes a table similar to an ANOVA table, and a box plot.

The subsequent section of the paper contains the descriptive statistics and the Kruskal

Wallis test mean scores on performance satisfaction on 24 different items and discussion

based on findings. Kruskal Wallis ANOVA test was run with help of MATLAB 7.1 to

derive mean rank. Further analysis was performed through multicompare (stats) tool in

KW statistics (this function is not available in SPSS 15). The objective was to identify

and attempt to label the homogeneous group extracted out of 24 different items derived

based on significant difference in CFO’s opinion on performance. Moreover, it was

thought to identify and relate homogenous categories or groups with significant

difference in score with the categories suggested by Otley (2002), Simmons (1995a),

Malcolm (2006), Franco-Santos et al. (2007) and discussed by us. Finally, the survey

results on use, and opinion about on the prevalent measurement practices from CFO’s

point of view is presented.

How does business performance measurement perform?

405

3.1 Findings and analysis

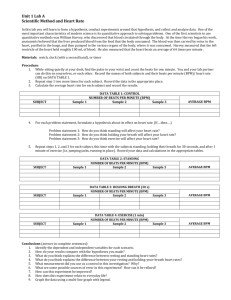

Table 2 depicts the Kruskal Wallis ANOVA table output from MATLAB 7.1, while the

Table 3 contains the Kruskal Wallis test mean score and descriptive statistics with the

ranks based on responses of CFO on how well those purposes or functions are satisfied. It

is observed that operational/tactical functions of the performance measures are well

satisfied compared to the function that represents strategic and intangible aspects.

Operational efficiency is rated highest in terms of satisfaction, followed by business unit

and divisions performance and so on. Comparably, Tonge et al. (2000) observed that the

main benefit of BPM (balanced scorecard) was that departmental goals were now

communicated well and being aligned with the overall business strategy. This indicates

that performance measurement is more focused on communicating and measuring

performance from short-term and operational perspective rather then on strategic and

behavioural one. Thus, reflects the use of BPM from the Simmons diagnosis and belief

control levers. Measuring performance of top management function (strategic and control

items or interactive control as argued by Simmons) falls amongst the list of lower

satisfied purposes, along with other stakeholder satisfaction, internal learning and growth,

employee satisfaction and social and environmental responsibility. Comparably, Tonge

et al. (2000) observed that balanced scorecard as a learning and feedback system was

seen as of least benefit in FTSE 100 companies. We find our results are mixed in

comparison with the longitudinal case by Tuomela (2005), which found that the company

they studied was in the development process and the main objective of the BPMs was

strict strategic control (i.e., diagnostic control) and at lower priority on to making sense

of strategy and learning about strategic interdependences (i.e., interactive control).

Table 2 on KW ANOVA Met Lab output depicts that at the significance of

0.05 levels there exist enough evidence to conclude that there is difference amongst the

performance across different purpose/function. High Chi Sq statistics reflects the strength

of our results.

A further attempt was made to find the difference in the average performance score

across the function/purpose category we proposed. Our proposed categorisation discussed

earlier in literature review sections builds on Otley’s (2002), to apply to a border

perspective, i.e., the entire organisational or business performance was discussed in the

literature section. Table 4 depicts the four function category wise scores. The MATLAB

mean comparison chart across various functions based on post hoc analysis using

multicompare (stats) in KW test can be seen in Figure 1.

Table 2

Source

Kruskal Wallis ANOVA table

SS

df

MS

Chi-sq

Prob > Chi-sq

Columns

4.74663e+006

23

206,375.3

84.79

5.22572e–009

Error

4.62496e+007

888

52,082.9

Total

5.09963e+007

911

406

K. Thaker

Table 3

Kruskal Wallis output mean score across different functions or purpose

Purpose

Mean

SD

KW mean

score

KW

rank

1

Information for developing strategy

2.18

0.83

457.82

13

2

Implementing strategy

2.13

0.78

445.70

11

3

Validating assumptions (strategy formulation premises)

2.39

0.89

517.87

19

4

Coordinating activities of several parts of the

organisation

2.08

0.67

433.43

10

Assigning responsibility to managers

Informing managers of the Performance pthat is

expected of them

7 Obtaining bases for evaluating Manager’s actual

performance

8 Compensating managers

9 Measuring business unit/division performance

10 To know the efficiency of management function

2.00

1.95

0.52

0.70

418.22

394.82

8

5

2.00

0.74

406.79

7

2.34

1.74

2.45

0.81

0.79

0.89

511.68

317.68

533.57

18

1

20

5

6

11 To know the effectiveness of management function

2.34

0.91

506.04

17

12 Meeting overall organisational long-term objective

2.24

0.82

481.80

14

13 Meeting overall organisational short-term objective

1.87

0.66

373.96

4

14 Product competitiveness

1.97

0.79

398.05

6

15 Customer satisfaction

2.05

0.73

424.70

9

16 Competitive position of company

2.13

0.81

451.92

12

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

2.47

2.45

2.61

2.42

2.26

1.71

1.84

2.24

0.92

0.80

0.89

0.83

0.72

0.52

0.72

0.63

545.09

541.57

587.72

538.76

496.47

319.95

359.14

493.24

23

22

24

21

16

2

3

15

Average score

Average expression

Rank

2.16

Tend to satisfy

2

2.19

Tend to satisfy

3

3.33

Tend to dissatisfy

4

1.99

Satisfy

1

Environmental sustainability

Social responsibility

Internal learning and growth

Employee satisfaction

Major pitfalls/risks of business

Operational efficiency

Share holders returns

Other stakeholders satisfaction

Table 4

Category

I

II

III

IV

Function category wise satisfaction score

Purpose/function category

Performance measures

(manifests) as major objective

of a business organisation

Performance measure as tool

for strategy formulation and

implementation.

Performance measures tool

to measure performance of

management function

management of business

Tool to manage and control

functional and divisional

performance

How does business performance measurement perform?

Figure 1

407

Multiple comparison of mean rank column Met Lab output (see online version

for colours)

The function Category III, in the Table 4, i.e., to know the performance on management

function appeared to be least satisfied. Respondent on average were not sure, and

generally rated low on how well the purpose is satisfied. A few companies like Mphasis,

Infosys and Wipro all from IT consulting and BPO industry have expressed satisfaction

in case of function Category III. A leading consumer electronic company CFO argued

that the present state of affairs in company is partly due to failure of BPM to adequately

fulfil functions given in Category III. Companies are most comfortable in terms of

satisfaction in Category IV function, i.e., measurement of functional performance,

Followed by the function Category I, i.e., to know how well overall objective of firm are

satisfied. Special attention needs to be given to the management functions category to

gear up the performance management of the management function. This reflects the need

to strengthen the interactive lever of control. Within the function categories there exist

heterogeneous response in terms of satisfaction. If we take individual functions and the

level of satisfaction then:

a

learning and growth

b

other stakeholder are least satisfied amongst all the function.

Employee satisfaction, social responsibility, the efficacy of management function and

sustainability are the ones with the satisfaction score on lower side. Say the respondent

CFO’s are of the view that their organisations are yet to recognise those items as one of

the important benefits they can derive from BPM.

Figure 1 in form of MATLAB 7.1 output on multiple comparison of mean rank chart

depicts a typical comparison of item 9 (measuring business unit/divisional performance)

with eight different functions. It shows that eight function mean scores and ranks are

significantly different from item 9. One can observe that measuring business unit and

408

K. Thaker

divisional performance have significantly better performance (satisfaction) compared to

the eight functions namely item 2, Validating assumption for strategy formulation

(interactive control), items 10 and 11 on effectiveness and efficiency of management

function, item 17 to 20, respectively on environmental, social, internal learning and

growth (illumination) and employee satisfaction. This clearly substantiates our earlier

inference that BPM performance on measuring business unit performance (tactical

issues) is significantly better then on the strategic, development and sustainability

aspects/category consisting of strategic validation, management learning and

development and environmental, social and employee stakeholder performance. The

Figure 1 only depicts comparison of item 9 with other groups, however, one can try

clicking on each function (group) one by one to observe that that function items 9, 13, 22

and 23 representing mainly the category groups 2 and 3 (given in objective and rational

section earlier), namely performance measures as measurement tool and performance

measures manifests major objective of a business (diagnosis lever of control) are

significantly better in terms of performance compared to the items 3, 10, 11, 17, 18, 19

and 20 representing the categories 1, 2 and 7 (given in objective and rational section) that

represents strategic, management development and learning and sustainability.

Comparably, Tuomela (2005) findings based on case-based research observed that the

use of strategic PMS was more prevalent for diagnosis and belief levers of controls

(Simmons, 1995a, 1995b), which relates well with the function categories 1, 2 and 4

given in the Table 4 above. While the use of PMS for interactive control is not much

prevalent as found by Tuomela relates well with our findings of low satisfaction score in

functional Category III in Table 4. Our study revealed that the performance management

systems are better performing in terms of aiding operational and organisation control, say

the level focus perspective suggested by Malcolm (2006), as it lags at strategic level.

Hence, the Simmons diagnosis and belief control function is better satisfied while

companies still lag in term of its BPM performance in terms of interactive control.

Figure 2 depicts the items that are significantly different.

Figure 2

MATLAB output on Kruskal Wallis test (see online version for colours)

How does business performance measurement perform?

409

The companies in our sample are amongst the most successful and leaders in respective

industry. Most of the companies are amongst the better performer in the industry. Such

success in performance is the result of good strategy and its implementation. This might

indicate the role of performance measurement system in success of those companies.

Hence, we could expect that higher performance satisfaction form BPM in those sampled

companies and our findings reflect this. However, should the sample would have

contained mid sized and other then leading companies the results may be different.

Further individual function specific inquiry on case-to-case basis can offer some useful

insights. We sum up by saying that we reject both hypothesis and conclude that.

•

First: There is significant difference in performance across different functions of

BPM.

•

Second: There is significant difference in performance across various groups

(function category) of BPM and it can be classified accordingly the various function

category and groups identified in the theory. This draws practitioner’s attention on

which lever of control or function category of BPM to work on to optimise benefits

from BPM implementation.

Table 5

Companies’ use and opinion about measurement practice (India)

% of respondents’ practices using/favourable

Measure of

Highly

valued

information

Financial

performance

87%

74%

92%

82%

63%

0%

Operating

efficiency

89

66

68

76

44

16

Customer

satisfaction

71

58

47

58

21

24

Employee

performance

45

45

58

53

53

16

Employee

satisfaction

47

29

37

37

18

37

Innovation/change

55

37

36

39

18

32

Internal business

process

71

60

53

53

34

13

Learning and

growth

47

42

32

53

16

42

4

Measures

Difficult

Quality of

Clear

Linked to

regularly

to

information measures

compensation

updated

measure

Quality, use and perceived importance of various financial and

non-financial measures

The replica of Wm. Schiemann and Associates 1996 survey on the quality, uses and

perceived importance of various financial and non-financial performance measures

(Lingle and Scheimann, 1996) included in the questionnaire has dome interesting

comparison. Table 5 depicts the disparities. Certain measures are highly valued but they

410

K. Thaker

are difficult to measure; not regularly updated, and are not institutionalised by linking

them to compensation. For instance, customer satisfaction, measures of operating

efficiency, employee performance, community and environment, and innovation and

change. Mostly, financial measures are linked to compensation. On the other hand,

non-financial measures are highly valued and offers quality information but only in very

few cases linked to compensation. The disparities across importance, use and clarity of

measures are comparable across the study in the USA and India.

5

Conclusions

This study explores and discusses BPM practice of top-notch companies in India. The

study is motivated to theoretically identify the purpose for which performance measures

are used and empirically research how well performance measures perform on the

purpose for which they are deployed and have some view of state of affairs on BPM in

select companies in India. In the literature, we found general agreement over the views on

the use-purpose of performance measurement in place and categorisation of purpose of

BPM. We have suggested four functional categories to describe use and purpose of BPM.

At a philosophical level, the purpose of BPM is to illuminate, inspire and integrated the

people and parts of the organisation towards the rightful purpose and organisational

objectives. Empirical studies we reviewed were found in western context and had

response ranging from 17 to 42 companies and contained wide variety of industry.

Overall, our survey results based on 38 leading companies in India preempts to conclude

that performance measures are better at satisfying tactical and operational purposes rather

then strategic and management function or say type 3 BS as suggested by Speckbacher

et al. (2003) purposes. This also draws us to say that users yet to realise full potential

benefits from the prevailing performance measurement systems in place. Overall, our

results concur with Tonge et al. (2000), that the use of BPM is seen primarily as a

performance measurement system – not as a strategic management system and also not as

management learning and development tool. Relating with Simmons levers of control,

the BPM performs better in terms of diagnosis and belief levers of control compared

to interactive lever of control. Performance measures are rather used as a tool

for management by objective and operational control (Malmi, 2001) rather then a

full-fledged strategic management system and a system that leads to management

learning and development (Neely and Al Najjar, 2006). This findings strengthen the

argument of earlier studies and results (Langfield-Smith, 1997; Abernethy and Brownell,

1999; Tonge et al., 2000; Vaivio, 2001; Bisbe and Otley, 2004) that it not only the

specific control tools such as BPM that are used but also that way they are applied and

used performance of those should be taken in to account. Moreover, it is found that

performance measurement has implications on four levers of control and that the users do

not realise benefits equally well across all of them. Users while implementing BPM must

think of its utility form border perspective, and explore its role as management learning

and development and strategic management system.

The survey on quality, use and perceived importance of various financial and

non-financial measures unveils disparities on use, quality of measurement. More

importantly, most executives had little confidence in any of their measures, with less then

50% willing to bet their jobs on the quality of their non-financial performance

How does business performance measurement perform?

411

information. Despite increasing importance of measures on customer satisfaction, internal

business process less then 40% of them are willing to bet their job and as low of in 16%

sample such measures are linked to compensation. Only in case of financial performance

related information none of the responded had difficulty in measurement. The results are

comparable with Lingle and Scheimann (1996).

The survey results are symptomatic of the maturity cycle in terms of usage,

understanding and potential for further realisation of benefits of BPM with reference to

companies in India. The sample appears fairly representative but the industry and sector

specific study results would differ. The sample represents large and leading companies in

respective sector, as it was believed that those companies would be suitable for

responding on BPM as are more likely to have higher maturity level of adoption. The

results could not be generalised for medium and small size companies and would be

difficult to study and replicate as such companies may not have such observably and well

developed of BPM in place. Nevertheless, the study points out the state of affairs and

some of the research issues and practical challenges with reference to BPM in India.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the encouragement and helpful advice of the

reviewers of the journal, Professor Manish Thaker for valuable advice on usage of

statistical tools and Mr. Ankit Sharma for valuable assistance in revising the paper.

References

Abernethy, M.A. and Brownell, P. (1999) ‘The role of budgets in organizations facing strategic

change: an exploratory study’, Acc. Org. Soc., Vol. 24, pp.189–204.

Anthony, R. (1965) Planning and Control Systems: A Framework for Analysis, Harvard University

Press, Boston, MA.

Bisbe, J. and Otley, D. (2004) ‘The effects of the interactive use of management control system on

product innovation’, Account. Organ. Soc., Vol. 29, pp.709–737.

Bititci, U., Carrie, A. and Turner, T. (2002) ‘Integrated performance measurement systems:

structure and dynamics’, in Neely, Andrew (Ed.): Business Performance Measurement:

Theory and Practice, Cambridge University Press.

Bourne, M.C.S., Mills, J.F., Bicheno, J., Hamblin, D.J., Wilcox, M. and Neely, A.D. and

Platts, K.W. (1999) ‘Performance measurement system design: testing a process approach in

manufacturing companies’, International Journal of Business Performance Measurement,

Vol. 1, No. 2, pp.154–170.

Bourne, M.C.S., Neely, A.D., Mills, J.F. and Platts, K.W. (2003a) ‘Implementing performance

measurement systems: a literature review’, International Journal of Business Performance

Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp.1–24.

Bourne, M.C.S., Neely, A.D., Mills, J.F. and Platts, K.W. (2003b) ‘Why some performance

measurement initiatives fail: lessons from the change management literature’, International

Journal of Business Performance Management, Vol. 5, Nos. 2/3, pp.245–269.

Campbell, D., Datar, S., Kulp, S. and Narayanan, V.G. (2002) ‘Using balance scorecard as a

control system for monitoring and revising corporate strategy’, Negotiation, Organization and

Markets Research Papers, Harvard NOM Research Paper No. 02-35, September.

412

K. Thaker

Chenhall, H.R. (2003) ‘Management control systems design within its organizational context:

findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future’, Accounting,

Organizations and Society, February–April, Vol. 28, Nos. 2–3, pp.127–168.

Chenhall, H.R. and Langfield-Smith, K. (2007) ‘Multiple perspectives of performance measures’,

European Management Journal, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp.266–282, Crown Copyright_2007

Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Epstein, M.J. and Manzoni, J-F. (2003) ‘Performance measurement and management control’,

A Compendium of Research by M.J., 1999–2003, Elsevier Sciences Ltd., The Netherlands.

Ferreira, A. and Otley, D. (2009) ‘The design and use of performance management systems. An

extended framework for analysis’, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 20, pp.263–282.

Franco-Santos, M., Kennerley, M., Micheli, P., Martinez, V., Mason, S., Marr, B., Gray, D. and

Neely, A. (2007) ‘Towards a definition of a business performance measurement system’,

International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 27, No. 8,

pp.784–801.

Govindrajan, V. and Gupta, A.K. (1985) ‘Linking control systems to business unit strategy:

effects on business-unit performance’, Accounting, organizations and Society, Vol. 10, No. 1,

pp.51–66.

Hollander, M. and Wolfe, D.A. (1973) Nonparametric Statistical Methods, John Wiley & Sons,

New York-Sydney-Tokyo-Mexico City.

Ittner, C.D. and Larcker, D.F. (1998) ‘Innovations in performance measurement: trends and

research implications’, Journal of Management Accounting Research, Vol. 10, pp.205–238.

Jean-Francois, H. (2006) ‘Are your performance measurement systems truly performing?’,

November, CMA Management, available at

http://www.enterpruner.com/tradejournals/article/print/164304475.htm

(accessed on 11 August 2010).

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D. (1996) The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action,

Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D. (2001) The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard

Companies Trive in the New Business Environment, Harvard Business School Press, Boston,

MA.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1992) ‘The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance’,

Harvard Business Review, January/February, Vol. 70, No. 1, pp.71–79.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (2006) Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create

Corporate Synergies, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Kellen, V. (2003) ‘Business performance measurement: at the crossroads of strategy,

decision-making, learning and information visualization’, available at

http://www.kellen.net/bpm.htm (accessed on 11 August 2010).

Khandwalla, P. (1972) ‘The effects of different types of competition on the use of management

controls’, Journal of Accounting Research, Autumn, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp.275–285.

Khandwalla, P. (1977) Design of Organizations, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York.

Koontz, H. (1959) ‘Management control: a suggested formulation of principles’, California

Management Review, Winter, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp.47–56.

Langfield-Smith, K. (1997) ‘Management control systems and strategy: a critical review’,

Accounting Org. and Society, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp.207–232.

Lingle, J.H. and Scheimann, W.A. (1996) ‘From balance scorecard to strategic gauges: is

measurement worth it?’, Management Review, American Management Association, March,

pp.56–61.

Malcolm, S. (2006) Performance Measurement and Management: A Strategic Approach to

Management Accounting, Sage Publication, London.

How does business performance measurement perform?

413

Malmi, T. (2001) ‘Balanced scorecards in Finnish companies: a research note’, Management

Accounting Research, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp.207–220.

Marr, B. (2009) ‘Business performance measurement: an overview of the current state of use in

USA’, available at http://www.emeraldinsight.com/Insight/viewcontentServlet?contentType

(accessed on 17 August 2010).

Marr, B. and Schiuma, G. (2003) ‘Business performance measurement; past, present, and future’,

Management Decision, Vol. 41, No. 8, p.6807.

Marr, B., Gray, D. and Neely, A. (2003) ‘Why do firms measure their intellectual capital’, Journal

of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp.441–464.

Meyer, C. (2007) Measuring the Future 2: Navigating the New Economy, Cambridge Marriott,

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Neely, A. (2002) Preface: Business Performance Measurement, Theory and Practice, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Neely, A. (2005) ‘The evolution of performance measurement research: developments in the last

decade and a research agenda for the next’, International Journal of Operations & Production

Management, Vol. 25, No. 12, pp.1264–1277.

Neely, A. and Al Najjar, M. (2006) ‘Management learning not management controls: the true

role of performance measurement’, California Management Review, Spring, Vol. 48, No. 3,

pp.101–114.

Neely, A., Mills, J., Platts, K., Richards, H., Gregory, M., Bourne, M. and Kennerelyy, M. (2000)

‘Performance measurement system design: developing and testing a process based approach’,

International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 20, Nos. 9–10,

pp.119–145.

Neely, A.D., Gregory, M. and Platts, K. (1995) ‘Performance measurement system design: a

literature review and research agenda’, International Journal of Operations & Production

Management, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp.80–116.

Otley, D. (1999) ‘Performance management: a framework for management control systems

research’, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp.363–382.

Otley, D. (2002) ‘Measuring performance: the accounting perspective’, in Neely, A. (Ed.): Business

Performance Measurement, Theory and Practice, Cambridge University Press.

Reilly, G.P. and Rambhala, K. (2001) ‘Developing managers through performance measurement’,

Journal of Cost Management, November/December, Vol. 15, No. 6, p.39, Boston.

Rigby, D. (2001) ‘Management tools and techniques: a survey’, California Management Review,

Winter, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp.139–160.

Simmons, R. (1995a) ‘Control in an age of empowerment’, Harvard Bus. Rev., Vol. 67, No. 2,

pp.80–88.

Simmons, R. (1995b) Levers of Control: How Managers Use Innovative Control Systems to Drive

Strategic Renewal, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Simons, R. (2000) Performance Measurement and Control Systems for Implementing Strategy,

Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Speckbacher, G., Bishop, J. and Pfeiffer, T. (2003) ‘ A descriptive analysis on the implementation

of balanced scorecard in German speaking countries’, Management Accounting Research,

Vol. 13, No. 4, p.36187.

Thaker, K.B. (2005) ‘Innovation in business performance measurement: review of studies, trends

and practices’, 1 June, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1412649.

Thaker, K.B. (2010) ‘Business performance measures: a study with reference to companies in

India’, Finance India, June, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp.535–542.

414

K. Thaker

Thakur, M., Burton, G.E. and Srivastava, B.N. (2001) ‘Organizing and controlling for international

competitiveness in international management’, in International Management, Concept and

Cases, Tata McGraw Hill.

Tonge, R., Larsen, P. and Pepper, J. (2000) ‘Balanced scorecards and the FTSE 100: exploratory

research’, International Journal of Business Performance Management, Vol. 2, No. 4,

pp.293–310.

Tuomela, T-S. (2005) ‘The interplay of different levers of control: a case study of introducing

a new performance measurement system’, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 16, No. 3,

pp.293–320.

Vaivio, J. (2001) ‘Non-financial measurement in an organizational context: three perspectives’,

PhD thesis, Helsinki School of Economics and Business Administration.

Verbeeten, F.H.M. (2005) ‘New performance measures: determinants of their use and their impact

on performance’, 14 October, ERIM Report Series Reference No. ERS-2005-054-F and

available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=902729.

Wiersma, E. (2009) ‘For which purposes do managers use-balanced scorecards? An empirical

study’, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp.239–251.

Notes

1

2

Interactive control is term used, based on the research of Robert Simons, Levers of Control

(Harvard Business Press, Boston, 1995b)

BS 200, the Business Standard daily contains the top 200 stocks of companies accounting for

85% of the value of shares on the two leading bourses of India. The Stock Exchange Mumbai

and the National stock Exchange.

How does business performance measurement perform?

415

Appendix

Sample companies and respondents

Company

Respondent

Designation

1

ABB Ltd.

K. Rajagopal

Sr. VP and Chief Financial

Officer

2

Alembic Ltd.

R.K. Baheti

Director and President

Finance

3

Arvind Mills Ltd.

Jayesh Shah

Director Finance

4

Biocon Ltd.

Murali Krishnan KN

Chinappa MB

President Group Finance,

VP Finance

5

BPL Limited

P.V.K. Sundaram

Vice President Finance

6

Cadbury India Ltd.

Girish M. Bhatt

Finance Director (SE Asia

and Indian Sub Continent)

7

Denial Measurement and

Control India Ltd.

Lalit Chhaya

Finance Controller

8

Dr. Reddys Laboratories

V.S. Vasudevan

Chief Financial Officer

9

Essar Steel Ltd.

V. Raghwan Biju Mathew

Chief Financial Officer,

General Manager Finance

10

FAG Precession Bearings

Ltd.

N. Ram Mohan

Chief Financial Officer

11

General Motors India Ltd.

Pranay Mehta

General Manager Finance

12

GCMMF

J.M. Soni

General Manager Finance

13

GACL

K.P. Buch

General Manager Finance

14

GNFC

Deepak S. Taunk

Executive Director

15

Godrej Sara lee Ltd.

Ravi Venkateswar

Chief Financial Officer and

Director Finance

16

Gujarat Gas Ltd.

Harbinder Singh

Ahluwalia

Finance Director

17

GlaxoSmithKline

Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Mehernosh Kapadia

Director and Chief Financial

Officer

18

Grasim Industries Ltd.

Sanjeev Bafna

Sr. VP Corporate Finance

19

Hewlett Packard India Ltd.

(Digital Global soft Ltd.)

Chandrasekar Sundaram

Manager Corporate Affairs

20

Hero Honda Motors Ltd.

Ravi Sud

Chief Financial Officer

21

Hindustan Lever Ltd.

S.P. Mustafa

Vice President M&A,

Treasury, Investor Relations

22

Hindalco Industries Ltd.

R.K. Kasliwal

Group Executive President

and Chief Financial Officer

23

Infosys Technologies Ltd.

T.V. Mohandas Pai

Member of Board and Chief

Financial Officer

24

I flex Solutions Ltd.

Deepak Ghasisas

Chief Executive Officer –

India Operation and Chief

Financial Officer

25

Indian Hotels Ltd.

L. Krishna Kumar

Sr. Vice President – Finance

416

K. Thaker

Sample companies and respondents (continued)

Company

Respondent

Designation

26

Mastek Software Ltd.

Jamshed B. Jussawalla

and Hitesh Danak

General Manager Finance,

Investor Relation Manager

27

Mphasis BFL Ltd.

Ravi Ramu

Chief Financial Officer

28

Nirma Ltd.

R.L. Joshipara

General manager Finance

and Accounts

29

Reliance Industries Ltd.

Alok Agarwal

President Finance

30

Sonata Software Ltd.

Thomas K. Joseph

Sr. VP and Chief Financial

Officer

31

Tata Telecom (Avaya) Ltd.

Amal Thakor

Chief Financial Officer

32

Tata Steel Ltd.

R.C. Nandrajog

Vice President Finance

33

Tata Motors Ltd.

Praveen Kadle and

R.S. Thakur

Chief Financial Officer,

General Manager Corporate

Finance

34

Tata Chemicals Ltd.

P.K. Ghose and

Rajveev Lodha

Chief Financial Officer and

Sr. Manager Accounts

35

Torrent Pharmaceuticals

Ltd.

Sanjay Dalal, Samir Shah

Executive Director Finance,

Vice President Finance

36

Transpek Silox Ltd.

P. Sreekumar

Vice President Finance and

Accounts

37

Wipro Ltd.

Suresh C. Senapaty

Corporate Executive and

Vice President Finance

38

ZydusCadila Cadila

Healthcare Ltd.

M.K. Patel

Sr. VP finance