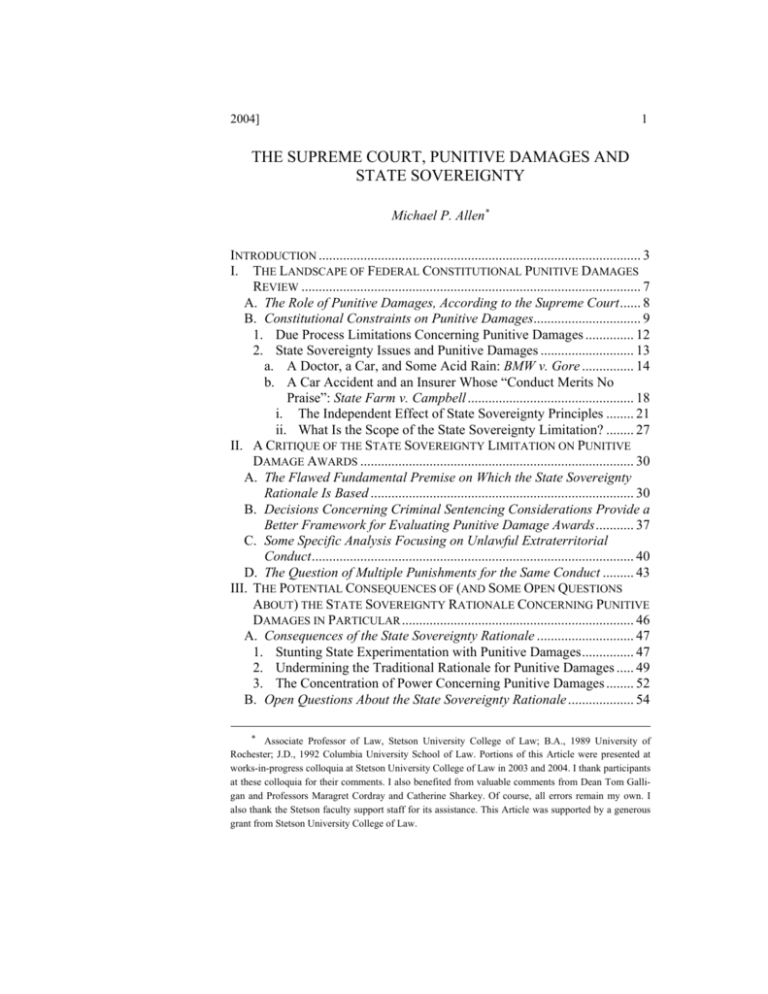

the supreme court, punitive damages and state sovereignty

advertisement