Response to Intervention: A Model for Dynamic

advertisement

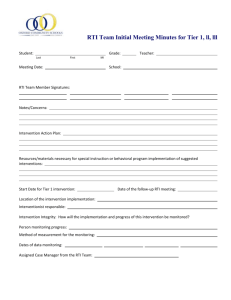

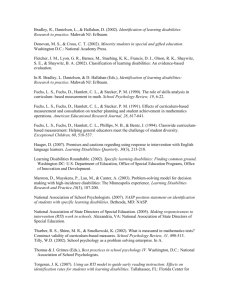

Response to Intervention: A Model for Dynamic, Differentiated Teaching The Dynamics of Dynamic Teaching Effective teachers plan meaningful, engaging lessons that maintain a fine balance between teaching content and teaching the processes for learning and thinking. As a lesson unfolds, good teachers act diagnostically, assessing students‘ response at each step. Based on measured responsiveness, instructors mediate learning (remove misunderstandings) by differentiating instruction, materials, and or group size, ensuring that all learners succeed (O‘Connor & Simic, 2002). Such seamless coordination of ongoing assessment and differentiation creates dynamic, synergistic teaching (Rubin, 2002; Walker, 2004). It‘s the initial step in a Response to Intervention (RTI) Process where responsiveness indicates the extent of the learner‘s achievement as a result of re-teaching (intervention) specifically designed to address problems. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Key Concepts Teaching diagnostically: teaching with continuous assessment of the learners’ level of understanding, areas of confusion, and other factors that affect success followed by appropriate instructional adjustments. Dynamic teaching: involves the analysis of changes in students’ performance during instruction as well as probes of learners’ responses as a foundation for successive instructional steps. A Description of RTI RTI is an instructional model that supports success for all students through prevention, intervention, and identification. RTI models offer multiple levels (tiers) of interventions based on children‘s responsiveness to student-centered instruction and assessment. Fuchs and Fuchs (2009) suggest that the major goal of RTI is ―to prevent long-term, debilitating academic failure‖ (p. 41). RTI strives to guarantee universal access to achievement. Initial high quality instruction from well-trained teachers prevents most problems. Continuous dynamic teaching with ongoing assessment directs appropriate and timely differentiation before difficulties escalate. When some children still fail to © Taylor and Francis 2012 achieve, systematically planned interventions adjust intensity, duration, group size, materials, and instructional strategies as the teacher mindfully mediates learning (eliminates misunderstanding). Individual responses to instruction at each point are carefully documented (Torgeson, 2009) in an RTI process. Continued and persistent lack of success leads to identification for special services. It‘s concluded that the child‘s lack of progress, despite systematic interventions provided by well-trained teachers, is caused by a disability; he needs specialized services that support learning (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Fundamental components in a school‘s RTI framework are designed to create an effective system for meeting all students‘ educational needs. The RTI Process RTI begins with universal screening (assessment) of all students‘ strengths and needs (social, emotional, and academic). Results from multiple formal and informal assessments are synthesized to determine students‘ baseline status. Effective classroom teaching, using research-based instructional approaches, is planned with knowledge gained from the screening. Ongoing progress monitoring and data analysis across intervention levels (NRCLD, 2007) allow teachers to note small changes and adjust instruction accordingly. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Most RTI models have three tiers of intervention (Berkeley, Bender, Peaster, & Saunders, 2009). Others differ in the number of levels, the person(s) responsible for intervention delivery at specific levels, and whether the process precedes identification for special education or becomes the eligibility screening for special services (Fuchs, Mock, Morgan, & Young, 2003). Key Concepts Universal screening: a type of quick and economical assessment that allows repeated testing of all children on age appropriate skills. Research-based instructional approaches: include methodology that can trace a connection to research as justification of usefulness. Levels of Intervention Fuchs & Fuchs (2009) advocate for a consistent RTI model with three levels— primary (tier 1), secondary (tier 2), and tertiary (tier 3). Some states have four tiers; the fourth tier becomes identification of eligibility for special education (Berkeley et al., 2009). A few states have additional levels with increasingly more specialized conditions for treatment, size of group, and time requirements. Fuchs et al. (2003) caution that instruction at higher tiers typically becomes increasingly © Taylor and Francis 2012 more disconnected from the classroom, making sustainable achievement difficult. Too many levels lessen intervention potency because of a ―well-known inverse relationship between instructional complexity and fidelity of implementation, the greater the number of levels, the less practical RTI becomes‖ (p. 168). Regardless of the number, assessment is ongoing across tiers of intervention and incorporates multiple measures. Tier 3 - 5% of population. Intensive intervention in very small group or individualized. Tier 2 - 15% of population. Targeted group intervention Tier 1 - 80% of population. Core Instructional Interventions in the Classroom Figure 1 Three-tiered model for RTI Source Bender & Shores, 2007; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2007; NASDSE, 2006; Vaughn Wanzek, Woodruff, & Linan-Thompson, 2006 © Taylor and Francis 2012 Standardized and Standard Measures As noted, students potentially at-risk are identified with universal screening (school-wide) measures (Fletcher, Lyon, Fuchs, & Barnes, 2007) early in a school year (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). In some schools, the previous year‘s standardized test data on a school-wide level is used to target students below a certain percentile. Standardized tests are generally regarded as formal (rigidly objective) measures, although their claims of objectivity have been challenged (Johnston, 1992). Lyman (1998) describes a standardized test as one that ―has set content, the directions are prescribed, and the scoring procedure is completely specified. And there are norms against which we can compare the scores [convert actual score to standard scores—e.g. percentiles, stanines] of our examinees‖ (p. 27). Locally determined assessments are often used to support or refute the strength of standardized test results. In addition to or in place of standardized tests, schools also consider whether established benchmark levels on a standard measure have been reached. An assessment is standard when it is consistently administered and scored according to specific directions (Shea, 2006). I call these formalized informal measures because the administration procedure is consistent (formalized), but the results are not reported in standard scores (informal). Using a range of standard measures, data on learning is gathered © Taylor and Francis 2012 during lessons as well as at the end of them; it‘s done throughout a unit of study as well as at the culmination point. Formative and Summative Assessment in RTI Criteria defining responsiveness should be clear and universally applied It‘s also critically important that teachers are well trained in multiple forms of formative (ongoing, during lessons) and summative (used at conclusion of lesson, unit, or grade) assessments and can administer them with fidelity (consistency in administration and scoring) (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2004). Formative assessment occurs ―in the moment, within the lesson‖ (Shea, Murray, & Harlin, 2005, p. 142). Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, and Wiliam, (2004) state ―assessment becomes ‗formative‘ when the evidence is actually used to adapt the teaching work to meet learning needs‖ (p. 10). That‘s the same as dynamic teaching. Formative assessment—on the way to summative ones—identifies learning gaps in time to ameliorate them. Ongoing assessment with a variety of sources has long been considered good teaching practice (Black et al, 2004). It increases equity and efficacy in any decision making process. Summative assessments are ―collected at the end or after the fact‖ (Shea et al., 2005, p. xvi; Wiggins, 1998) identifying who didn‘t fully learn the concepts or skills in the lesson, unit, or larger block of content. These students didn‘t reach © Taylor and Francis 2012 the benchmark. Benchmarks constitute an established point of reference against which a learner can be measured (Shea et al., 2005). Assessment on a benchmark point becomes criterion-referenced. In other words, the child‘s performance during and following the intervention is compared to anchor responses that represent ―known standards of credible development‖ (Wiggins, 1998, p. 246). Children deemed to be nonresponsive to (not benefiting from) instruction at any level receive interventions that become increasingly individualized or geared toward their specific need (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Thus, ―data about a student‘s responsiveness to [each] intervention becomes the driving force‖ (Grimes, 2002, p. 4) for planning further instruction. But, when only summative measures are used, learning difficulties are not identified with timeliness—in time to nip them in the bud. The educational and human consequences of that are huge and unacceptable. A combination of assessment types increases overall student achievement and leads to more accurate identification of nonresponders. Multiple Measures for Identifying Specific Learning Disabilities (SLDs) In line with the requirement of multiple criteria for determining learning disabilities, the Learning Disabilities Summit concluded that the following inclusionary criteria should be in place for SLD identification (Bradley, Danielson, & Hallahan, 2002). The learner‘s: © Taylor and Francis 2012 1. response to instruction, assessed through ongoing progress monitoring with appropriate measures, is inappropriate and/or insufficient. 2. low achievement on state-approved grade level academic standards has also been corroborated by state and/or national standardized measures. 3. low achievement is not caused by environmental, language differences, or intrinsic factors that have been excluded (NRCLD, 2005, p. 3). Compatible with the conclusions of this Summit, IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) 2004 allows funds to be used for RTI services since interventions at successive tiers offer additional data for sound decision making on the eligibility (for special education) question. Beyond funding interventions, the law explicitly states that children can only be identified for special education services with documented evidence that low achievement is not the result of inadequate instruction (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009). Noting that current models for RTI are not especially sensitive to culturally and linguistically different students, Klinger and Edwards (2006) propose a model that integrates culturally sensitive instruction, differentiation, and assessment throughout all tiers of intervention. © Taylor and Francis 2012 The Trigger for Intervention When the child is nonresponsive to instruction—as determined by documented observation and valid assessment measures—interventions in successive tiers are initiated (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009). Interventions include increased time, smaller group size, different instructional strategies, or individualization when deemed necessary (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009). Children‘s responsiveness to these adjustments (i.e. their measured learning) is examined. Fuchs & Fuchs (2006) emphasize that it‘s the student‘s ―classroom performance [on curricular objectives], rather than test performance, that determines responsiveness and eventual special education eligibility‖(p. 95) as children move through degrees of intervention. Determining Eligibility for Special Education Typically, placement in special education is considered only after all interventions have been exhausted. How long that takes varies; more tiers and longer intervals within each increase time for intervention and postpone eligibility decisions. Delayed transitioning through tiers brings the efficacy of any local RTI model into question. © Taylor and Francis 2012 In a review of state models, Berkeley et al. (2009) confirm that most states delay decisions on special education eligibility until the child‘s responsiveness to tier 3 interventions has been fully evaluated. This makes any fourth tier a special education placement. Other states allow initiation of special education referrals in tier 2, making it possible that tier 3 is an initiation of special education services. In the latter case, tier 3 (tertiary) interventions are done with the resources and expertise of special education professionals (Fuchs, Stecker, & Fuchs, 2008). A few states allow special education referrals at any step in the RTI process (Berkeley et al., 2009). Although criticized for inconsistency, RTI models are conceptualized to improve on discrepancy models for SLD identification. Significant Discrepancy Model When SLDs were initially added as a category of disability in 1977, the U.S. Office of Education indicated that a significant discrepancy (large enough difference) between measured IQ and expected achievement would determine eligibility for identification (Mercer, Jordan, Allsop, & Mercer, 1996). In essence, the discrepancy model historically compared measured IQ with academic achievement to determine if a large enough gap existed between the two for a particular learner (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009). © Taylor and Francis 2012 Often, this left children languishing; it took time within the educational system to create the significant gap. In the meantime, children struggled, fell farther behind, became frustrated, and lost self-confidence (Drame & Xu, 2008; Fletcher, Lyon, Barnes, Stuebing, Francis, & Olson, 2002). This perpetuated a longstanding and widespread ―wait to fail‖ policy (Vaughn & Fuchs, 2003, p. 139) . Other concerns with the discrepancy model were the overrepresentation of minorities in special education, over- and under-identification of disabilities, and biased referral and/or assessment protocols for special education (Donovan & Cross, 2002; Drame, 2002). Thus, the discrepancy formula discriminated equally. Too often, children in need struggled for a long time before they were identified or help never came. On the other hand, labels were attached to children who were more instructionally deprived than learning disabled (Fuchs et al., 2003). Finally, the discrepancy model lacked immediate utility; it offered little information for planning initial interventions. Further complicating matters, states were allowed to decide on measures and standards of achievement in determining the discrepancy, leading to considerable variability in the processes used and numbers of children identified (Reschly & Hosp, 2004). © Taylor and Francis 2012 Inflated Numbers: Misdiagnosis Although there was some under-identification, typically the opposite was true using the discrepancy mandate. It‘s estimated that between 1977 and 1994 the number of students identified with disabilities rose from 8.3 to 12.2 percent of the student population. SLDs increased from 22 to 46 percent of identifications for special needs students while enrollment in public schools remained constant during that period (Hanushek, Kain, & Rivkin, 2001). Since 1977, identification of students with SLDs has increased 200 percent causing many to suspect misdiagnosis with false positives (over-identification of students with high IQ and low achievement) and false negatives (underidentification of those with low IQ and below-average achievement) (Vaughn, Linan-Thompson, & Hickman, 2003). Many began to question the efficacy of SLD criteria. © Taylor and Francis 2012 False negatives False positives True positives Description Relationship to Relationship to Problem-solving Standard Model Protocol Model Children do well in higher levels of intervention, but fail to thrive when in classroom. Children who appear nonresponsive and disabled demonstrate they are neither with effective instruction. Children who really need services are identified. Model less Model likely to likely to identify identify false false negatives negatives Model more likely to identify false positives Model likely to identify true positives Figure 2 False Negatives versus False Positives Continued and sometimes contentious debate of the discrepancy model led to research, resulting in critical analyses related to definitions of and identification processes for SLDs (Johnson, Mellard, & Byrd, 2005). With diligence, the chance of error can be greatly reduced, but some is unavoidable. Educators continued to © Taylor and Francis 2012 seek greater accuracy in distinguishing disability from lack of achievement due to environmental and/or instructional factors (NRCLD, 2005). Although some still have concerns about it, RTI emerged as a solution to over and under-identification of SLDs (Vaughn & Fuchs, 2003). A Paradigm Shift: Origins of RTI While RTI is considered a relatively new approach by most, the concept is rooted in research that dates back to the 1960s (Bender & Shores, 2007). RTI appears to have been influenced by informal pre-referral models established by schools seeking ways to lessen over-identification. By the mid-1980s, pre-referral procedures gained momentum; they were widely viewed as a solution to over-identification. Pre-referral amounted to teacher modifications in the classroom (with instruction or environment) aimed at meeting the needs of specific learners. The teacher or a team of educators from various fields determined the nature of modifications. This process appeared to lessen inappropriate referrals and validate the legitimacy of alternatives (Fuchs et al., 2003); it may have influenced later legislation. Before IDEA, 2004 was re-authorized, the President‘s (President Bush) Commission on Excellence in Special Education (2002) was given the charge of evaluating the current status of special education at all levels in the country. A © Taylor and Francis 2012 conclusion of that group was that effectively delivered early interventions could lessen learning disability (LD) identification—the largest population of students identified for special education services (Drame & Xu, 2008). When passed, IDEA 2004 incorporated a recommendation for intervention before special education eligibility decisions are made. IDEA 2004 allows, but doesn‘t mandate, schools to implement RTI as they move away from discrepancy models for identifying children with SLDs. Replacing the Discrepancy Model Although RTI models are not nationally mandated, states are required—under the re-authorization of the IDEA of 2004—to decide whether there‘s something more reliable than historically used discrepancy formulas for identifying SLDs. The new requirement led to swift implementation of some form of RTI in school districts across the country (Berkeley et al., 2009; Bradley et al., 2005). Berkeley et al. (2009) report that fifteen states have adopted an RTI model and are in the process of implementation, twenty-two are developing a statewide model, ten are providing guidance to districts working toward a local model, and three have yet to adopt any RTI process. A few states have timetables for when the discrepancy model for identification of SLDs will be phased out and/or eliminated. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Regardless of whether or not the state has a specific RTI model in place, 88 percent of them are providing staff development on the concept, using university and/or state resource centers. California has created a video, Response to Intervention Training for California Educators; it‘s available via Webcast and DVD (Berkeley et al., 2009). RTI constitutes a significant policy shift in determining eligibility for special education services (Drame & Xu, 2008). Drafts for language in the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act/No Child Left Behind (2007) noted that RTI was required in state plans as a possible intervention model or approach for low performing schools (Council for Exceptional Children, 2007). Two distinct models and numerous variations of RTI have emerged. Common Threads in RTI Models Whether a model is used in its purest form or created as a hybrid (blended version), RTI implementations have similar components. Common steps include: 1. well-trained teachers providing all students with effective, appropriately differentiated in-the-classroom instruction. 2. continuous, detailed progress monitoring during and after instruction to determine those still at risk. © Taylor and Francis 2012 3. multi-leveled interventions that systematically incorporate more intense interventions in smaller groups for more time (Coleman, Buysse,& Neitzel, 2006). Struggling students get something else or something more from their teacher or someone else. Students who need more challenging work also have needs met. 4. Continuous, detailed progress monitoring of children receiving an intervention. 5. Review of eligibility for special services for those who remain nonresponsive to instruction (Fuchs et al., 2003). The first step in any RTI model is teacher effectiveness; it‘s the teacher that makes the difference (Cole, 2003). That factor can significantly lessen the number of children who need further interventions. An assessment of teacher effectiveness at tier 1 is essential. This is accomplished by comparing the overall rate of student achievement in a teacher‘s classroom to that of similar classrooms in the building and/or district (Drame & Xu, 2008). Achievement should also be evaluated for students in particular subgroups (e.g. gender, linguistic background) within and across grades and schools to determine if there are differences in patterns of progress (Drame & Xu, 2008). Marston (2005) emphasizes the importance of tier 1 for RTI success stating that ―general education teachers must assume active responsibility for delivery of high quality instruction, research based interventions, and prompt identification of © Taylor and Francis 2012 individuals at risk while collaborating with special education and related service personnel‖ (p. 541). Children who continue to demonstrate nonresponsiveness (i.e. don‘t improve) on benchmarks for progress are identified for more intensive intervention in small groups of three to five students for 20–40 minutes a day. This is tier 2— secondary intervention in all models. Children who continue to show nonresponsiveness on tier 2 intervention are selected for more intensive instruction in smaller groups or individualized for increased time periods (45–60 minutes daily) with a specially trained professional (e.g. literacy specialist, special education teacher, speech teacher). This comprises tier 3—tertiary intervention. Some schools allow tier 3 interventions to be delivered in very small groups; others provide intensive individualized instruction by a specialist at that point (Berkeley et al., 2009). Two Models and Numerous Hybrids There is no singular mandated model or process for RTI. Schools adopt and adapt tenets of RTI when designing implementation for their site. For success, RTI delivery must be a collaborative, integrated effort by general education, special education, Title I and other support services (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009). © Taylor and Francis 2012 Currently used RTI models have roots in two approaches that represent efforts to ameliorate or prevent academic difficulties (Division for Learning Disabilities, 2007). Berkeley et al. (2009) report that two-thirds of the fifteen states using RTI have implemented a hybrid version with elements from both approaches. They note that practitioners favor a hybrid or problem-solving model while researchers favor the standard protocol model. In each model, classroom teachers are the first line of defense in a war against a learner‘s failure to thrive. Walker-Dalhouse, Risko, Esworthy, Grasley, Kaisler, McIIvain, and Stephan, (2010) suggest that ―teachers assuming responsibility for adjusting instruction according to students‘ specific needs rather than following a predetermined skill sequence … provide timely mediation of problems when they occur‖ (p. 85). However, the shift in practice is not easy to achieve. RTI requires new ways of thinking and collaborating as a continuum for prevention and intervention is implemented in the school. All models emphasize high quality teaching and differentiation; they also link with special education, ensuring that students who remain at-risk despite levels of intervention are screened for special needs. A universal screening, using local or state standardized achievement test and/or standard benchmark assessment, identifies children who are potentially at-risk. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Problem-Solving Model Tier 1 Well-trained teachers provide effective differentiated instruction for all children during initial instruction and carefully evaluate and document children‘s success on curricular objectives. A student‘s responsiveness to instruction is referenced to the performance of the larger population of students on local and/or state standards for the grade. Tier 2 Intervention in small group incorporating valid, instructional practices deemed appropriate for the individuals in the group with careful evaluation and documentation of children‘s responsiveness. Team designed plan for intervention can be completed by the classroom teacher, teaching assistant under supervision, or a resource teacher (e.g. literacy specialist). Tier 3 Fuchs, Stecker, & Fuchs (2008) suggest that this level is conducted with the resources and expertise of special education professionals. Hybrid Model: A blended model that incorporates elements from the problemsolving and standard protocol model. Standard Protocol Model Tier 1 Well-trained teachers provide effective differentiated instruction for all children during initial instruction and carefully evaluate and document children‘s success on curricular objectives. A student‘s responsiveness to instruction is referenced to the performance of the larger population of students on local and/or state standards for the grade. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Tier 2 Intervention in small group incorporating research-tested, instructional treatment that educators have been trained to use with fidelity. The same instructional treatment is use for all children identified with a specific problem; it‘s usually implemented outside of the classroom (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Detailed documentation of their responsiveness is evaluated. Tier 3 Fuchs, Stecker, & Fuchs (2008) suggest that this level is conducted with the resources and expertise of special education professionals. Figure 3 Two distinct models for RTI … and hybrids that blend elements of each Problem-Solving Model One model involves a problem-solving process (Donovan & Cross, 2002; Reschly & Tilly, 1999). Fuchs et al. (2003) claim that a key feature of the problem-solving model is that it is inductive—involving a search for explanations. No specific category (gender, race, suspected disability, socio-economic status (SES), demographic, or other variability) dictates the intervention no matter how exclusive the group may appear to be. Possible solutions for a child‘s nonresponsiveness to instruction are collaboratively induced (reasoned from an analysis of pieces to a conclusion—from particulars to general) after a thorough examination of progress monitoring data. The problem-solving model or a hybrid model of it is more often selected by states and school districts; it traces its © Taylor and Francis 2012 foundation to earlier pre-referral models previously discussed (Burns, Vanderwood, & Ruby, 2005). In the problem-solving model a child study team, comprised of school professionals from various disciplines and areas of expertise, examine the case of a student experiencing behavioral and/or academic difficulty. Collectively, they propose an intervention strategy intended to solve the problem; the team proposes how, when, and where the strategies will be applied. Ongoing data as well as teacher observations, reflections, and conclusions are collected during the intervention. The team analyzes this collection of information when it reconvenes to consider the status of the problem and possible next steps from that point. Across this shared decision making process, effective communication and collaboration are essential (Haager & Mahdavi, 2007). The problem-solving model is cyclical; steps are repeated. It‘s also triatic. It includes the classroom teacher, consultant(s) (e.g. literacy specialist, special education teachers) (Allington, 2009), and the student throughout the following stages: 1. a definition of the problem expressed in observable, measurable terms; 2. collection of baseline data focused on the identified problem using a variety of useful, reliable assessments to determine the severity, context, and frequency of the problem; © Taylor and Francis 2012 3. design of an intervention plan after a thorough analysis of data collected; 4. implementation of the plan; 5. ongoing monitoring and documenting of progress during implementation to determine the child‘s responsiveness; and 6. revision of the plan, including re-definition of the problem (back to #1) based on the child‘s progress (Fuchs et al., 2003; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Standard Protocol Model As in sites using a problem-solving or hybrid model of RTI, classroom teachers in schools with a standard protocol model receive staff development on research validated practices. They apply these techniques for differentiating instruction when delivering tier 1—primary or preventive intervention in their classroom. Classroom teachers include primary targeted interventions as part of their core instruction (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2007). When learners are nonresponsive to primary interventions, the standard protocol model calls for the use of a standardized, research validated treatments (manner of instruction and/or resources used) in tiers 2 and 3 of intervention. Specific to the standard protocol model is that the intervention at levels beyond tier 1 involves ―the use of the same empirically validated treatment for all children with similar problems in a given domain‖ (Fuchs et al., 2003, p. 166) © Taylor and Francis 2012 offered by educators trained to implement the specific treatment with fidelity. Fuchs et al. (2003) suggest advantages for this model; everyone knows what to implement, a large number of children receive an effective intervention, and those doing the instruction are trained to deliver it with fidelity. However, there‘s also criticism of standardizing treatments. Allington (2009) states that ―there is no reason to expect that any single intervention focus will be appropriate‖ (p. 33) for all students in a category. Rather than relying on a specific commercial program, effective teachers use multi-leveled, multi-genre resources in activities geared toward individual needs (Allington & Johnston, 2002). They understand that the most potent interventions begin with a good match between the student, the task, and the learning outcome (Allington, 2009). Across all RTI models there‘s a continuous pull between prevention and identification of SLDs; the key is balancing resources for effectiveness in both realms. Making RTI Work Regardless of whether a site chooses to use the problem-solving, standard protocol, or a hybrid model, considerable effort and finances must be extended to make it work seamlessly and effectively. All teachers need to be trained in © Taylor and Francis 2012 collaboration, problem identification, problem-solving, differentiated instruction, specific assessment tools, instructional practices, and progress monitoring. Staff development should particularly emphasize instruction, materials, and assessment sensitive to cultural and linguistic diversity (Drame & Xu, 2008). It‘s no surprise that students, particularly those at-risk, are less likely to learn in classrooms that lack high quality instruction, strong organization, effective management, and respect for diversity (Donovan & Cross, 2002). The National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE) (2006) states that competent professionals with noted expertise in particular areas of training should be hired by schools to conduct staff development (SD); they should be invited to return for follow-up sessions and consultation. Schools can‘t expect teachers to be fully competent after one-shot staff development presentations. Many schools have begun implementing RTI—even with limited resources— (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009) while others have been experimenting with various forms of intervention over the past twenty years (Jimerson, Burns, & VanDerHeyden, 2007). Examples of successful district-wide RTI implementation can be found across the U.S. (Jimerson, et al, 2007; NASDSE, 2006). The number of states using RTI increases as educators realize the possibility of providing all children with whatever they need to reach their full potential. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Document Progress with Curriculum-Based Measures (CBMs) Along with universal screening, the RTI process begins with teacher observation during day-to-day instruction in the general education classroom. Although they often consult with colleagues, share ideas, and elicit suggestions, classroom teachers are responsible for delivering high quality, differentiated instruction to all students in their classroom (Drame & Xu, 2008). Once potential at-risk students are identified, a system for continuous monitoring is initiated. Such monitoring may be brief (1–3 minutes per student) or slightly longer to determine a student‘s responsiveness to instruction. It involves a reliable, valid CBM—one associated with desired academic outcomes identified by the school for students at that level (Stecker, Fuschs, & Fuchs, 2005). Although there‘s concern about the quality of particular instruments (Francis, Santi, Barr, Fletcher, Varisco, & Foorman, 2008), teachers understand that appropriate assessments pinpoint sources of confusion when administered effectively and accurately interpreted in a timely manner. Targeted instructional adjustments that follow have the potential to resolve most problems (Fuchs, Deno, & Mirkin, 1984). Reducing the number of children experiencing extended difficulties allows schools to direct resources and personnel toward those who continue to need additional help (VanDerHeyden, Witt, & Gilbertson, 2007). © Taylor and Francis 2012 Running Records: Formative and Summative Curriculum-Based Measures Running Records (RRs), discussed in the text associated with this website, meet the requirements for a valid, useful assessment tool when used effectively. They provide a reliable CBM of literacy acquisition. There isn‘t another assessment that provides as much information on a child‘s literacy development as a running record. It‘s efficient, timely, and reliable data that‘s immediately available and highly useful for planning targeted instruction (Shea, 2000). As previously mentioned, Fuchs and Fuchs (2006) recommend that in-theclassroom performances on curriculum-based objectives be the measure of responsiveness to instruction. RRs indicate a reader‘s fluency of decoding and depth of comprehension on a leveled text selection. Successful reading performance involves an integration of these multiple skills for text and meaning processing. The information gleaned from a running record of the child‘s oral reading and retelling has direct instructional utility. It‘s used to plan the next teaching step. Formative RRs provide information ―on-the-spot, increasing the likelihood that materials, objectives, instruction, and learning activities are on target‖ (Shea, 2006, p. 16). © Taylor and Francis 2012 Sometimes RRs are administered as a benchmark measure, determining the learner‘s level of performance at a given point in time and comparing that to an expected target score. When RRs are taken for this purpose, Shea (2006) suggests the following protocol. The reading passage is new. It hasn‘t been previously heard or read by the student. Standard procedures for administering and scoring the record are followed. The reader works independently throughout the assessment Running records assess multiple aspects of a child‘s literacy development (e.g. decoding skills, fluency, vocabulary knowledge, comprehension, and expressive language skills) in a reasonably short period of time. Accumulated RRs present evidence of growth or lack thereof in each component as well as the child‘s ability to fluidly integrate skills. The text associated with this website introduces the marking codes for each kind of miscue that readers make. It also further suggests when and why teachers use RRs for formative and benchmark data. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Extending the Discussion • Review the following article to examine where your state falls in the RTI national initiative. An online version of the article can be found at: http://ldx.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/42/1/85. Published by Hammill Institute on Disabilities and Sage. Berkeley, S., Bender, W. N., Peaster, L. G., & Saunders, L. (2009). Implementation of Response to Intervention: A snapshot of progress. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 85–95. • Discuss local RTI practices in a faculty meeting. What‘s working well? Where could changes be made? © Taylor and Francis 2012 Bibliography Allington, R. (2009). What really matters in response to intervention. New York, NY: Pearson. Allington, R. & Johnston, P. (2002). Reading to learn: Lessons from exemplary 4th grade classrooms. New York, NY: Guilford. Bender, W. N. & Shores, C. (2007). Response to intervention: A practical guide for every teacher. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Berkeley, S., Bender, W. N., Peaster, L. G., & Saunders, L. (2009). Implementation of response to intervention: A snapshot of progress. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42 (1), 85–95. Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Working inside the black box: Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 86, 9–21. Bradley, R., Danielson, L., & Doolittle, J. (2005). Response to intervention. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38 (6), 485–486. Bradley, R., Danielson, L. & Hallahan, D. (Eds.). (2002). Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Burns, M. K., Vanderwood, M. L., & Ruby, S. (2005). Evaluating the readiness of pre-referral intervention teams for use in a problem-solving model. School Psychology Quarterly, 20 (1), 89–105. Cole, A. (2003). It‘s the teacher, not the program. Education Week. March 12, p. 3. Coleman, M. R., Buysse, V., & Neitzel, J. (2006). Recognition and response: An early intervening system for young children at risk for learning disabilities. Full report. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, FPG Child Development Institute. Council for Exceptional Children (CEC). (9/5/2007). Untitled letter to Chairman Miller and Ranking Member McKeon. Retrieved 9/25/2007, from www.cec.sped.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Content_Folders&TEMPLATE =/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=8905. Division for Learning Disabilities. (2007). Thinking about response to intervention and learning disabilities: A teacher’s guide. Arlington, VA: Author. Donovan, M. S. & Cross, C. T. (2002). Minority students in special and gifted education. National Research Council Committee on Minority Representation in Special Education. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Drame, E. (2002). Sociocultural context effects on teachers‘ readiness to refer for learning disabilities. Exceptional Children, 69 (1), 41–53. Drame, E. & Xu, Y. (2008). Examining sociocultural factors in response to intervention models. Childhood Education, 85 (1), 26–32. Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Barnes, M., Stuebing, K. K., Francis, D. J., & Olson, K. R. (2002). Classification of learning disabilities: An evidence-based evaluation. In R. Bradley, L. Danielson, & D. P. Hallahan (Eds.). Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice, pp. 185–250. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Fuchs, L. S., & Barnes, M. A. (2007). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. New York, NY: Guilford. Fletcher, J. M. & Vaughn, S. (2009). Response to intervention: Preventing and remediating academic difficulties. Child Development Perspectives, 3 (1), 30–37. Francis, D. J., Santi, K. L., Barr, C., Fletcher, J. M., Varisco, A., & Foorman, B. R. (2008). Form effects on the estimation of students‘ oral reading fluency using DIBELS. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 315–342. Fuchs, D. & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41 (1), 93–99. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Compton, D. L. (2004). Identifying reading disability by responsiveness-to-instruction: Specifying measures and criteria. Learning Disability Quarterly, 27, 216–227. Fuchs, D., Mock, D., Morgan, P. L., & Young, C. L. (2003). Responsiveness-tointervention: Definitions, evidence, and implications for the learning disabilities construct. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 18 (3), 157–171. Fuchs, D., Stecker, P. M., & Fuchs, L. S. (2008). Tier 3: Why special education must be the most intensive tier in a standards-driven, No Child Left Behind world. In D. Fuchs, L.S. Fuchs, & S. Vaughn (Eds.), (2009). Response to intervention: A framework for reading educators, pp. 71–104. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Fuchs, L. S. & Fuchs, D. (2007). A model for implementing responsiveness to intervention. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39, 14–20. Fuchs, L. S. & Fuchs, D. (2009). On the importance of a unified model of responsiveness to intervention. Child Development Perspectives, 3 (1), 41–43. Fuchs, L. S., Deno, S. L., &. Mirkin, P. K. (1984). The effects of frequent curriculum-based measurement and evaluation on student achievement, pedagogy, and student awareness of learning. American Educational Research Journal, 21, 449–460. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Grimes, J. (2002). Responsiveness to interventions: The next step in special education identification, service, and existing decision-making. Paper presented at Office of Special Education Programs LD Summit Conference, Washington, DC. Haager, D. & Mahdavi, J. (2007). Teacher roles in implementing interventions. In D. Haager, J. Klinger, & S. Vaughn (Eds.), Evidence-based reading practices for response to intervention, pp. 245–264. Baltimore MD: Paul H. Brookes. Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J. F., & Rivkin, S. G. (2001). Inferring program effects for specialized populations: Does special education raise achievement for students with disabilities? Unpublished manuscript. Jimerson, S. R., Burns, M. K., & VanDerHeyden. A. M. (2007). Handbook of response to intervention. Springfield, IL: Charles E. Springer. Johnson, E., Mellard, D. F., & Byrd, S. E. (2005). Alternative models of learning disabilities identification: Considerations and initial conclusions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 569–572. Johnston, P. (1992). Constructive evaluation of literate activity. New York, NY: Longman. Klinger, J. K. & Edwards, P. A. (2006). Cultural considerations with response to intervention models. Reading Research Quarterly, 41 (1), 108–117. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Lyman, H. (1998). Test scores and what they mean (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Marston, D. (2005). Tiers of intervention in responsiveness to intervention: Prevention outcomes and learning disabilities identification patterns. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 38, 539–544. Mercer, C., Jordan, L., Allsop, D. & Mercer, A. (1996). Learning disabilities and criteria used by state education departments. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 19, 217–232. National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE). (2006). Response to intervention: Policy considerations and implementation. Alexandria, VA: Author. National Research Center on Learning Disabilities (NRCLD). (2005). Responsiveness to intervention in the SLD determination process [Brochure]. Lawrence, KS: Author. O‘Connor, E. A. & Simic, O. (2002). The effect of reading recovery on special education referrals and placements. Psychology in the Schools, 39 (6), 635–646. Reschly, D. J. & Hosp, J. L. (2004). State SLD policies and practices. Learning Disability Quarterly, 27, 197–213. © Taylor and Francis 2012 Reschly, D. J. & Tilly, W. D. (1999). Reform trends and system design alternatives. In D. Reschly, W. Tilly, and J. Grimes (Eds.), Special education in transition, pp. 19–48. Longmont, CO: Sopris West. Rubin, D. (2002). Diagnosis and correction in reading instruction. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Shea, M. (2000). Taking running records, New York, NY: Scholastic. Shea, M. (2006). Where’s the glitch?: How to use running records with older readers, grades 5–8. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Shea, M., Murray, R., & Harlin, R. (2005). Drowning in data?: How to collect, organize, and document student performance. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Stecker, P. M., Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (2005). Using curriculum-based measurement to increase student achievement: Review of research. Psychology in the School. 42, 795–819. Torgesen, J. (2009). The response to intervention instructional model: Some outcomes from a large-scale implementation in reading first schools. Child Development Perspectives, 3 (1), 38–40. © Taylor and Francis 2012 VanDerHeyden, A. M., Witt, J., & Gilbertson, D. (2007). A multi-year evaluation of the effects of a response to intervention (RTI) model on the identification of children for special education. Journal of School Psychology. 45, 225–256. Vaughn, S. & Fuchs, L. S. (2003). Redefining learning disabilities as inadequate response to instruction: The promise and potential problems. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 18, 137–146. Vaughn, S., Linan-Thompson, S., &. Hickman, P. (2003). Response to treatment as a means of identifying students with reading/learning disabilities. Exceptional Children, 69, 391–409. Walker, B. (2004). Diagnostic teaching of reading (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. Walker-Dalhouse, D., Risko, V. J., Esworthy, C., Grasley, E., Kaisler, G., McIIvain, D., & Stephan, M. (2010). Crossing boundaries and initiating conversations about RTI: Understanding and applying differentiated classroom instruction. The Reading Teacher, 63 (1), 84–87. Wiggins, G. (1998). Educative assessment: Designing assessments to inform and improve student performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. © Taylor and Francis 2012