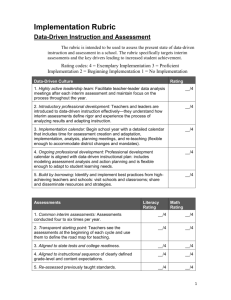

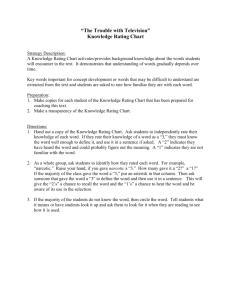

teacher effectiveness

advertisement