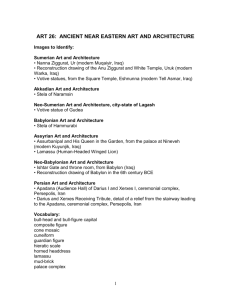

the full report

advertisement