The Coxoh Colonial Project and Coneta, Chiapas Mexico: A

advertisement

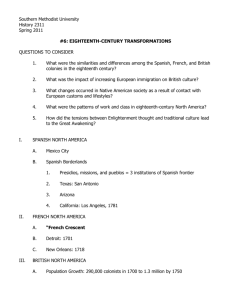

(Vogt 1971a, l971b) used in Chiapas. This particular interest was carefully integrated with the long range objectives of the Foundation (Lee 1974, 1W5). The Coxoh Colonial Project and The Coxoh Colonial Project has three basic concerns. First, it is an attempt to identify and Coneta, Chiapas Mexico: describe the heretofore unknown culture hisA Provincial Maya Village tory of an indigenous Maya-speaking group of a single region through the combined techUnder the Spanish Conquest niques of archaeology and ethnohistory. At the time of the Conquest, this group of extinct Coxoh Maya occupied the natural region conABSTRACT forming to the uppermost drainage basin of the The Brigham Young University-New World Archaeo- Grijalva River near the present border of Mexlogical Foundation is developing an interdisciplinary ico and Guatemala. Moreover, the material research program focused on the upper Grijalva River culture baseline developed for this specific, basin which was occupied at the time of the Spanish conquest principally by indigenous Coxoh Mayan- linguistically identified people will be used in speakers. Five important Coxoh villages have been the future as a solid point of reference in the identified and located in this region and excavtions are comparative study of material from earlier planned at all of them. periods. During the spring of 1975, three months were spent Finally, and most importantly, the project mapping and excavating at Coneta, one of the five villages, in order to investigate the processes of Coxoh was developed in order to study the process of acculturation. Of particular interest to the investiga- acculturation in the Upper Grijalva River tions are changes in domestic and ceremonial architec- drainage, as seen from the combined points of ture, community pattern, diet, ceramics, and other as- view of archaeology and ethnohistory. The pects of material culture. Such changes are important in understanding syncretic changes in the social sys- project provides the opportunity to view the tems including kinship, residency, land ownership, and culture change process under tightly conagricultural techniques. trolled cultural, linguistic, chronological and A primary function of the archaeological and ethno- spacial parameters. The plan is to focus on a historic study of such Colonial sites is the establish- time period with sufficient historical resources ment of a social and material culture base line of known linguistic affiliation (Coxoh Maya) to serve as a point of to allow the linguistic identification of the departure for comparisons in future investigations in group involved, and also to provide a minimal the same region at purely pre-Hispanic sites. This pa- ethnohistoric description of their culture. per explains the origin and purpose of the Coxoh Proj- Other important ingredients include a situaect, summarizes the results of the first field seasan and tion in which sufficient time has passed for details some of the more important aspects of the acacculturation to affect the archaeological macultivation process. terial culture or the discernment of a contact situation of sufficient impact to make itself felt on the material culture of the group in quesIntroduction tion. Either of these factors alone would be of The Coxoh Colonial Project (Figure 1) is a sufficient importance to make the study effort joint effort of the Brigham Young University- worthwhile. The fact that both are present in New World Archaeological Foundation and the time period of the Spanish Conquest of the Duke University; the authors are the principal region and the subsequent 300 years of Coloinvestigators. This project developed quite nial rule only enhances the possibilities of the naturally out of a long-standing desire of the project’s success. senior author to pursue a direct historical apThe study of the process of Coxoh conquest proach project based on the genetic model acculturation provides another example of this THOMAS A. LEE, JR. SIDNEY D. MARKMAN THE COXOH COLONIAL PROJECT 57 FIGURE 1. Map of a portion of southeastern Mexico. The heavily shaded area indicates the three munciph of Trinitaria. Comolapa and Chicomuselo in which the 6.Y.U.-New World Archaeological Foundation is developing the Upper Grijalva River Basin Project. special type of culture change situation. It may also result in an explanation of this phenomenon on a broader level. Such information would be useful in formulating the diagnostic elements for understanding conquest acculturation dynamics in prehistoric archaeological situations. Here, the components are often postulated, but rarely well defined and even less well understood. The interest in attempting the Coxoh Maya archaeological ethnohistorical project also stems from a definite lack of such an integrated approach in Mesoamerica. It is a known fact that archaeologists have rarely taken advantage of the great possibilties which are available to them in the combined study of archaeological and ethnohistorical resources in Mesoamerica. The number, magnitude, and high level of cultural attainment in Mesoamerica is commonly known. Ruins abound, and most are closely tied, often for not very scientific reasons, to rather exotic indigenous peoples. Perhaps of less common knowledge outside the profession of anthropology and history, is the abundance of documents written for over half a millennium on all regions of Mesoamerica. These lie in hundreds of archives. Thousands of tons of documents, in Spanish and Latin, principally, lie molding away in county, 58 state, and national archives, and there is a surprising lack of interest in the archaeological community to take advantage of them. The Coxoh Project was specifically designed to attempt to tap these rich if often difficult documentary resources. The gathered information is not always dramatic, but it is never unproductive. A new date, the name of an Indian group, a reference to some strange custom, no matter how small the new information, all is grist for the mill. All new evidence leaves one in a better position to phrase hypotheses, to guide tests, and to explain results. In spite of the archival work, to date, no documents written in Coxoh are known to exist. The group is, however, amply referred to throughout the early Colonial period in travel accounts, parish appointments of priests, and govermental - documents (Feldman 1972, 1973a, 1973b; Ponce 1948). The lack of a document or vocabulary in Coxoh means that the exact linguistic position of the language in relation to the surrounding Maya languages is not previously known. Geographically, the Coxoh occupied a hot lowland valley near the center of the monolithic block of Maya-speaking peoples. The Mam, Jacaltec and Chuj peoples, living on the northwestern slopes of the Cuchumatane Mountains of Guatemala, border the Coxoh temtory on the east. To the south, down the Grijalva River Valley, the Chicomuseltec and Tzeltal adjoin the Coxoh area while the Tojolabal are found to the north in the southern end of the Chiapas Highlands. All of these languages except Mam and Chicomuseltec are part of the Western Maya Branch (Kaufman 1974: 85). There are good archaeological and linguistic reasons to believe that Chicomuseltec, now also extinct, is not related intimately to the Coxoh (White 1974). Whether Coxoh ultimately proves to be more closely related to the Mam or Jacaltec-Chuj block on the east or the Tzeltal on the north and west, is purely academic since its relative linguistic position is rather narrowly defined and seems quite clear. HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 11 During the Colonial period, the Coxoh occupied at least five villages as well as an unknown number of ranches, isolated farms and other small kin-based nucleations of settlement in the hinterland around the villages (Figure 2). Three of the most important villages, Aquespala, Escuintenango, and Coapa, were located on the Camino Real that ran between San Cristobal de las Casas and Guatemala City, seat of the Capitania de Guatemala which also included the modem Mexican state of Chiapas. Escuintenango and Coapa were both overnight stopping points on this route. Coneta and Cuxu, the other Coxoh villages, were located well away from the Camino Real and can be expected to present a less intensive or more selective process of acculturation than the three towns in more intensive contact with the conquest culture. All of these towns, except Aquespala, are well preserved since they occupy areas long dedicated to cattle raising rather than intensive cultivation. The masonry church convent complex at most towns is quite well preserved, but more importantly, the rest of the town around it is in excellent condition despite its abandonment for over 100 to 200 years. The street system of most is cleary visible. Domestic house remains in patio complexes front onto the streets. Dry wall masonry terraces and stone walls along property limits are common interpatio divisions. Small round masonry sweat baths are found within the patio complexes. Larger open spaces, sometimes along the side of the patio complex, but more often directly behind it, were surely dedicated to houseplot cultivation, running space for domestic fowl and small animals, and relief area for the human inhabitants of the patio complex. Coneta: Mapping and Excavations During .the spring of 1975, three months were dedicated to the field study of Coneta, one of the better preserved Coxoh villages. With the aid of topographer Deanna Gum, a detail map with a scale of 1500 and a contour interval of one meter was made of the site. A THE COXOH COLONIAL PROJECT 59 FIGURE 2. A map of the Upper Grijalva River basin indicating the location of five extinct Colonial Coxoh Maya villages and the “Camino Real” which passed through the area. total of 87 domestic houses, 16 sweatbaths, three churches (one with associated convent and enclosing walls), and numerous terraces and other man-made structures were mapped. The street system of Coneta is not especially well preserved, but it can be seen to a limited extent in the northwest and southwest sectors of the site. A flat area with evidence of heavy occupation immediately adjacent to the south side of the church atrium and extending southward for some 60 meters was ploughed by the present owner many years ago. Individual patio complex patterns and probable street systems were completely obliterated. The main church (Figure 3) with the beautifully preserved facade and convent was the focus of effort at Coneta. All measurements of this important structure were taken, and pre- 60 FIGURE 3. The San Jose Coneta church convent complex, built in the last quarter of the 17th century. liminary drawings were produced later in the laboratory. The complicated facade was drawn under especially difficult conditions, and many return trips were needed before the drawings were complete and accurate. The construction date for the church is not exactly known, but stylistically it would not seem likely that it was earlier than A.D. 1610. A 1699 document that requested a reprieve from four years’ tribute to rebuild the community church suggests either that the church had fallen into disrepair, or as is more probable, replaced an earlier church (Archivo General de Guatemala 1677: A 1.24). An earlier structure of three rooms was indeed located by the excavations; it has been named the “Primitive Church (Figure 4).” The largest of the three rooms is long and nar- FIGURE 4. Adobe walls and stone quoined doorway of the 16th century “Primitive Church.” HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 11 row and has a raised platform with three steps rising to it on the western side. A small room opens off the east end of this large room. A second, smaller room with a low porch on the south side adjoins the middle room on the latter’s east side. The entire structure is of adobe with porous limestone quoins about the doors and om the three steps in the larger room leading to the altar or platform which occupied the entire west end of the room. The “Primitive Church” is completely devoid of roof tile fragments, among its debris; this is unlike the larger and later church convent. The lack of roof tile probably means that the church dates to the beginning of the community before tile was made locally. The construction technique of adobe walls and limestone quoined entrances is repeated in the churches of Aquespala and Escuintenango which stylistically are earlier than the larger Coneta church convent. It surely means that the “Primitive Church” had a perishable roof, probably of grass, much as do the domestic houses of the community and which are still generally found throughout the nearby countryside. Inside the most eastern room and near its east wall, was a small, square, raised masonry hearth which had been heavily burned. The thin lime plaster floor had also been burned to a dull red for about one meter all around the hearth. Among other artifactual materials collected from the floor around the hearth were small, lead-like spher’es the size of shot. It would appear that in the beginning of the Colonial period at Conel.a, the Sword and the Cross were very much together. A third church near the northern edge of the site was tested and has a completely different type of wall construction and altar form. It was probably built during the last occupation period of the site. It may well date to a brief 20th (century reoccupation of Coneta. Interviews scheduled for the spring of 1977 with the few known living members of this reoccupation will be designed to establish the construction date of this church. Associated with the church/convent complex ,are three groups of human interments. THE COXOH COLONIAL PROJECT 61 FIGURE 6. Colonial domestic house excavation at Coneta. the surface and was never underlain by more than another 20 cm of cultural fill. The houses are believed to have had grass roofs with walls made of wattle and daub. SinFIGURE 5. Colonial masonry tomb in the Campo Santo gle o r imultiple courses of dry-laid rock wall located in the San Jose Coneta church convent patio. footings and a more rocky type of wattle and Within the nave, near the main arch and at the daub wall construction were probably emfoot of a north window, several simple pit ployed and are still used throughout the area. burials are located. None of these is accom- This tylpe of construction is called coruzdn de panied by mortuary offerings. Outside the piedra. Both of these wall types leave very nave and to the north, within the Campo distinct and different patterns upon their disSanro or cemetery proper, the remains of sev- integration. The excavated houses fall into eral formal Colonial masonry tombs can still two grciups on the basis of the orientation of be seen (Figure 5). In the atrium, in front of their long axis. Five houses range between the church facade, 13 modem graves are pres- 41”-50” east of north, while the other three ent. Several of these show signs of having range bletween 80”-90” east of north. The more been cleaned and refurbished during the pre- northerly oriented houses do agree within two ceding “All Saints Day.” Several have wood- or three degrees with the “Primitive Church” en crosses with names and dates in the late and street orientation, suggesting that all three 1930s and early 1940s which can still be read. traits are related. Several domestic structures are definitely What is thought to be the church convent trash dump is located just north of the struc- arranged about patios with a porch either to ture outside the orchard wall and through the the side or behind but never found facing onto northern gate. Future comparison of the arti- the street. Rarely are more than two domestic factual and non-artifactual remains from the structures found in a patio complex. A small, dump will be the key to diet patterns, eco- circular sweat bath is clearly a member of the nomic status and interaction between the sec- patio complex (Figure 7). Sixteen of these ular and religious sections of the community. were m,apped, and eight were excavated. DisEight domestic house structures (WG of the tinctive sweat bath features include a large total) were excavated in 5 cm arbitrary levels rock wall footing, small doorway, formal (Figure 6). All fill was screened through one- hearth containing fire-cracked rock, and a half centimeter mesh screen. Domestic de- rock4a.b paved floor. No storage structures were recognized durposition was very shallow; the floor, when present, was rarely more than 20 cm below ing the field work at Coneta. Today, corn is 62 FIGURE 7 Sweat bath, part of the Coneta indigenous domestlc complex Note stone slab floor, hearth and firecracked rock inside the remains of the lowest course of the rock wall FIGURE 8. Tojolobal potters working inside home at the Morelia ranch near Coneta. Note corn storage behind potters. 4c harvested and dumped in a pile in the uncovered but fenced house patio. Not until just before the rains come, some five to six months later, is the remainder carefully placed in ricks inside the one room house. The storage pattern of corn during the Colonial period may have been similar to the present day situation (Figure 8). In at least two excavated domestic structures, large, deep, round pits filled with fire- HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 11 cracked rock and gray ash were found. Their specific use remains an enigma. The analysis and interpretation of the artifacts recovered at Coneta has not begun, and therefore little more than a few generalities can be made at this time. Two ceramic traditions, the native, characterized by crude red and brown wares in simple forms, and imported Spanish majolica decorated in blue, yellow or green, exist in all domestic situations tested in the community. Ground stone artifacts are common, especially manos and metetes, but stone axes are non-existent. Chipped flint and obsidian flakes and blades are common cutting implements, suggesting that despite the presence of iron tools, the latter were so rare and expensive that they were beyond the reach of the ir’digenous Inembers Of the community. Bone artifacts are also rare. Shells from the Pacific Ocean indicate that commerce with the Socoriusco coast was maintained. The diet of the Coneta Coxoh appears, on the basis of the preliminary analysis, to be one typical of Mesoamerican agriculturalists generally. The only surprising element is the presence in the excavation of over 48,000 common freshwater snail shells. They no doubt were the most significant single food species providing protein to both the convent and the Indian home. Other faunal remains show that almost all common domestic animals and many wild mammal, bird, and reptilian species were food for the larder. Not even the frequent cow and horse bones in the convent kitchen midden however, suggest the same intensity and continued use as that of the lowly snail taken from the Coneta River nearby. Syncretic Process of Acculturation From the first field season at Coneta the process of Coxoh acculturation can be characterized, at least early in the Colonial period, as one of syncretism. Syncretism refers specifically to the amalgamation of two different religious beliefs into one in which some attributes of both are present. The concept of syncretism can be applied not only to religion, but THE COXOH COLONIAL PROJECT to all other aspects of the community, material and social as well as ideological. Culture change is never a simple situation, and rarely is it characterized by a one to one, loss and gain. Some changes are weak, while others are dramatic and their origins clear. One of the obvious differences between the pre-Hispanic and the later Colonial villages, like Coneta, which immediately strike the observer is the community pattern. The complete lack of symmetry in the Late Postclassic sites in Chiapas contrasts dramatically with the relatively straight streets of uniform width and their arrangement into a grid forming squarish blocks in the Colonial communities. Before and after the anival of the Spanish, ceremonial structures, both secular and sacred, occupied the center of the community. A large open space around these structures has always been available for the congregation of large crowds for the purpose of religious, commercial, political, or purely social activities. Prior to the Conquest, this space was relatively unstructured and irregular in shape. Afterwards, it was always uniformly defined by the buildings which surrounded it, and access was limited to the streets which issued into it. The decisive change in community plan brought about by the Conquest is again seen in the presence of the single imposing religious structure of the Colonial community. This contrasts sharply with the native pattern characterized by several civil religious structures, almost all competing in importance and size with one another. Much has been written about Colonial and modem religious syncretism in Mesoamerica. It is clear that it is a special blend of Catholicism with indigenous polytheistic view (Foster 1954; Edmonson 1960; Orellana 1975; Corona 1972; Litvak King 1972; Nutini 1972; Jimenez Moreno 1972). Not so well known, however, is the fact that the Coxoh, as well as other Maya groups, shifted their descent and naming practices soon after the Conquest. They adopted the use of Spanish praenomina with a two-part birth date as the surname (Baroco 63 1970). The binomial birth day name, of course, came directly from the ancient Maya practice of naming a person after the day of his birth. A few years later, Coxoh children no longer took their own birth day name as a surname; rather, they adapted the Spanish custom of using the birth day name of their father. By 1600, even this vestige of the ancient Maya calendar and naming system was abandoned and one finds only the use of Spanish surnames among the Coxoh. The material remains at Coneta also demonstrate the amalgamation of material culture traditions, but to differing degrees. The “Primitive Church,” at first glance, appears to utilize no major native architectural traits in its construction, but there are at least two and perhaps more such traits. The orientation of the altar to the west is not a common Spanish trait and may reflect a native influence about which more will be said below. The fact that the entire ‘‘Primitive Church” is underlain by a thick, clean, large rock fill typical of all nearby Postclassic ceremonial structures, may indicate a desire by the builders, not the priests who were having it built, to elevate the stmcture. This is exactly in the Postclassic tradition, even if the structure did not attain the height of earlier pyramids. Obviously the later church/convent complex conforms more architecturally to Spanish norms than do its pre-Hispanic forerunners. Indigenous elements are limited to some possible decorative motifs on the facade (Figure 9). In the top register, below the belltower flanking, the central niche is a quadrifoil line and five circle motif vaguely reminiscent of the twisted reed glyph (Thompson 1%2: Glyph 615) present in the Maya glyph system. Directly below this motif is an even more amorphous one which has no pre-Hispanic parallels but which was certainly never part of the Catholic iconography. In the third register, just above the main door, is the round “rose” window which with the niche and flanking circles above it appears to form a large face. Large masks and mythical faces are common elements in Classic and Postclassic Maya tem- 64 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 11 lic and indigenous icons. The jaguar and the earth monster (on which the earth rests) are very important figures in pre-Columbian cosmology. Their omnipresent representations appear in paintings, sculptures, architecture, and pottery. The lion and dragon are common elements in Catholic, especially Dominican, iconography. The two plants which issue from the monsters’ mouth are thought to be squash (Cucurbita) represented mainky by its flower, and the prickly pear (Opunria) suggested principally by its fruit. A further example of syncretism is seen at the apex of the arch in which the santisima rests within the characteristiclly Late Postclassic long legged tripod bowl. In the domestic architecture there are no discernible Spanish traits. Apparently all strucFIGURE 9. Facade of the 17th century church at Coneta tures had grass roofs and wattle and daub walls with coursed stone footings and porches; they continued to be made in the tradition of the pre-Conquest Maya and do so to the present day. Among the artifacts, it has already been stated that Spanish majolica and a few metal and glass objects are about the only items introduced into the native material culture inventory. At least in the beginning, Colonial Spanish material culture made little impact on that of the traditional Maya. FIGURE 10. Line drawing of polychrome paintings on the The symmetrical, tightly organized grid arches over the door in the facade of the main church at community plan at Coneta is of Spanish oriConeta. gin, but its orientation of about 43“ east of ple facades. The sun bursts or multi-pointed north is more closely related to the alignment stars on the pilasters of the same register are of the: “Primitive Church” and some domestic also native elements, as are the double bifur- structures and follows the pre-Spanish oriencated tongue motifs which flank all of the tation of ceremonial centers. In contrast, the Spanish favored comunity plans oriented to the niches on this same level. By far the most dramatic example of religious points of the compass. syncretism on the facade occurs in the polychrome paintings on the arches over the main Conclusions doorway (Figure 10). Painted in red, black, The Colonial Coneta Coxoh Maya, like gray, brown and a pale yellow are angels, the many acculturated peoples elsewhere in the sun, corn plants, monsters with other plants world, tried to take their bad luck philosophissuing from their mouths, and the sanrisima or host. The angels, of course, are Catholic as ically. Where they were forced to change they are the monsters, although in the latter one did, but to make it a little more palatable they finds an interesting coincidence in both Catho- included a few elements of their own. THE COXOH COLONIAL PROJECT The Spanish Colonial policy contained two aims through domination-economic gain and conversion of the heathen. The policy required a change in the indigenous culture only insofar as it was expedient to the successful completion of its aims. Archaeologically, this is observable in the Coxoh settlement and community pattern, and in the ceremonial architecture. Seemingly pragmatic people, the Coneta Coxoh accepted other changes because they were practical, such as new domestic animals and plants, and a few new implements. Here it seems to have been a matter of cost versus efficiency. However, in matters such as religion, elements of the pre-Hispanic Maya religious system were carefully maintained. An excellent example of this comes from a nearby large Tzeltal Maya community. Almost a century after the foundation of Copanaguastla, the third church convent and community in the state to be established, the friars were horrified to discover that the Indians kneeling in prayer and devoutly crossing themselves before the Virgin of the Rosary, the beautiful patron saint of the town, were directing themselves not to her, but in the friars’ words “to the filthy graven idol” so carefully hidden behind her skirts by the ingenious native elders (Xemenez 1930 ( 1 I): 191-2). The process of Coxoh acculturation is certainly not as the song says “a many splendored thing,” but it is just as certainly a many faceted thing. One facet reflects a Spanish tradition, another an indigenous one, and a third something of both. All of them interact and are bonded tightly together as integral parts of a whole. REFERENCES ARCHIVO GENERAL DE GUATEMALA A 1.24 (1967) 10.209-1565, fol. 59, p. 5 . BAROCO, JOHN v. 1970 Notas Sobre el Nombres Calendaricas Durante el Siglo XVI. In Ensayos de Antropologb en la Zona Central de Chiapas, edited by Norman A. McQuown and Julian Pitt-Rivers. Coleccion de Antropologfa Social 8: 13548. Instituto Nacional Indigenista. Mexico, D.F. 65 CORONA, EDUARD~ S. 1972 Los Execrementos en el Proceso de Sincertismo. In Religion en Mesoamerica, edited by Jaime Litvak King and Noemi Castillo Tejero, pp. 52936. XI1 Meso Redonda of the Sociedad Mexicana de Antropologia, Cholula, Puebla, Mexico. EDMONSON, MONROES. 1960 Notivism, Syncretism and Anthropological Science. Middle American Research Institute, Publication 19. ,FELDMAN, LAWRENCE H. 1972 A Note on the Past Geogrpahy of Southem Chiapas Languages. Inernarional Journal of American Linguistics. 38: 57-8. 1973a Languages of the Chiapas Coast and Interior in the Colonial Period 1525-1820. Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility 18: 77-85. l973b Chiapas in 1774. Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility (18): 105-35. FOSTER,GEORGE 1953 Cofradia and Compadrazgo in Spain and Spanish America. Southwestern Journal of Anrhropology 9(1): 1-26. 1954 Reference missing JIMENEZ MORENO, WIGBERTO 1972 El proceso de sincretismo en Mesoamerica. In Religion en Mesoamerica, edited by Jaime Litvak King and Noemi Castillo Tejero, pp. 483484. XI1 Mesa Redonda of the Sociedad Mexicans de Antropologia, Cholula, Puebla, Mexico. KAUFMAN, TERRENCE 1974 Idiomas de Mesoamerica. Cuaderno 33. Seminario de Integracidn Social Guatemalteca. Guatemala. LEE,THOMAS A., JR. 1974 Preliminary Report of the Second and Final Reconaissance Season of the Upper Grijalva Basin Maya Project (January-May, 1974). Unpublished Ms submitted to the Departimento de Prehispanicos, INAH. Mexico, D.F. 1975 The Upper Grijalva Basin: A Preliminary Report of a New Maya Archaeological Project. In Bafnnce y Perspectiva de la Antropologia de Mesoamerica y del Norte de Mexico, Tom0 II, Arqueologia, pp. 3547. XI11 Mesa Redonda of the Sociedad Mexicana de Antropologia (September 9-15, 1973). Jalapa, Veracruz, Mexico, D.F. LITVAK KING, JAIME 1972 Introduccidn Posthispbica de Elementos a 10s Religiones Prehispanicas: Un Problem de Aculturacion Retroactiva. In Religion en Meso- 66 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, VOLUME 11 america, edited by J. Litvak King and N. C. Tejero, pp. 25-30. XI1 Mesa Redonda, Cholula, Puebla, Mexico. NUTINI,HUGOG. 1972 La Estructura Contemporania y el Desarrollo Historic0 del Ayuntamiento Religioso: Sincretisimo y Aculturacion. In Religion en Mesoamerica, edited by Jaime Litvak King and N ” i Castillo Terejo, pp. 511-12. XI1 Mesa Redonda of the Sociedad Mexicana de AntropoIO@, Cholula, Puebla, Mexico. ORELLANA, SANDRAL. 1975 La Introducci6n del Sistema de Cofradg en la Regibn del Lago Atitlih en 10s Altos de Guatemala. America Indigena 35(4): 845-56. PONCE,FRAY edition, pp. W. Centro de Estudios Mayas, Universidad Nacional Autbnoma de Mdxico, Mexico. 1971b Summary and Appraisal. In Desarrollo Culrural de 10s Mayas, edited by Evon Z. Vogt and Alberto Ruz L., second edition,.pp. 409447.Universidad Nacional Audnoma de Mdxico, Mexico. WHITE, JAMESM. 1974 The Results of the Archaeological Reconnaissance of Chicomuselo, Chiapas, Mexico, and a Trial Model to Explain the Collapse of the Late Classic in the Central Depression of Chiapas. Ms p r e y e d for advanced graduate seminar of ~ r . Knut Fladmark, Simon Fraser University. Winter. 1974. ALONSO 1948 Viaje a Chiapas. (Antologia). Cuadernos de Chiapas X N . (1586) Gobiemo Constitucional del Estado (de Chiapas). Departamento de Bibliotecas. Tuxtla Gutierrez. THOMPSON, J. ERICS. 1%2 A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. The University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. z. VOGT, EVON 1971a The Genetic Model and Maya Cultural Development. In Desarrollo Cultural de 10s Mayas, edited by Evon Z. Vogt and Albert0 Ruz L., second THOMASA. LEE BYU-NEWWORLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION h A R T A D 0 POSTAL 89 2A CALLE NORTEORIENTE NO. 4 COMITAN, CHIAPAS,MEXICO SIDNEY D. MARKMAN OF ART CHAIRMAN, DEPARTMENT DUKEUNIVERSW DURHAM, NORTHCAROLINA 27706