A Short Course in Psychiatry - Oregon Health & Science University

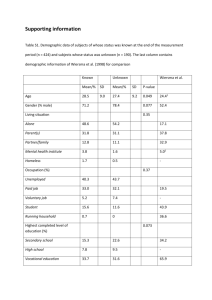

advertisement