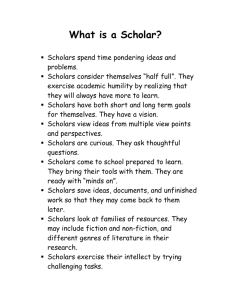

legal theory and legal education, 1920-2000

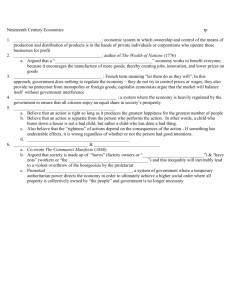

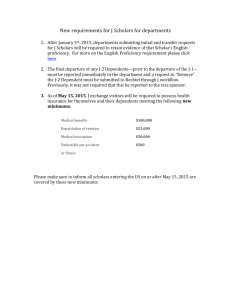

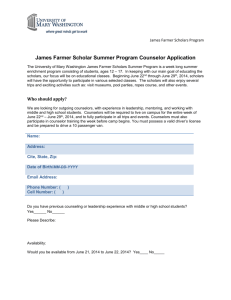

advertisement