Therapeutic Recreation Education in Canada

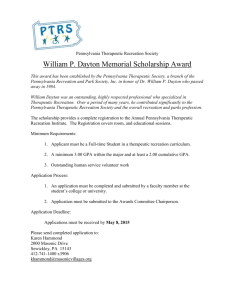

advertisement