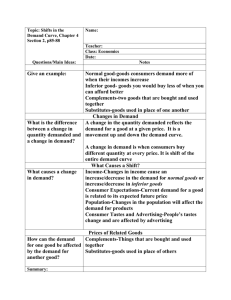

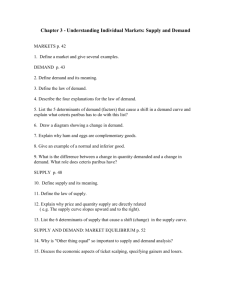

economics

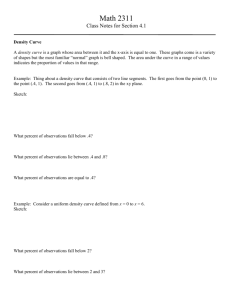

advertisement