Los Angeles Riots: Sa-I-Gu – From a Korean Women's Perspective

advertisement

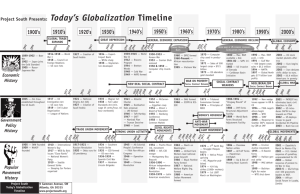

May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE Los Angeles Riots: Sa-I-Gu – From a Korean Women’s Perspective By Nancy Park The 1992 Los Angeles Riots (“L.A. Riots”) are not likely to be considered a transnational issue or event. In fact, many do not remember it as an “event” at all – at least not one that requires any deep analysis. Most sources describe the L.A. Riots as a three-day uprising that ensued after a majority-white jury acquitted four LAPD officers for the beating of black motorist Rodney King, noting that the targeting of Korean shop owners could constitute it as a race riot. Without regard for the structural, social, political, and economic factors that attributed to this upheaval, the L.A. Riots are often considered an inevitable result of a growing “Black-Korean conflict” in Los Angeles. In fact, popular culture eventually related it to other “natural” disasters on the infamous “I Survived LA in the 90’s” t-shirts that listed riots, fires, floods, and earthquakes together as the natural disasters of the decade. Today, the L.A. Riots are most commonly related to the popular catch-phrase, “Can’t we all just get along?” This paper will complicate traditional understandings of the LA Riots by analyzing several aspects of the film, Sa-I-Gu: From a Korean Women’s Perspective. While presenting the L.A. Riots through a transnational lens, Sa-I-Gu also works to shed some light on transnational ideas of racial formations/relations, nation and the American Dream. This is achieved through interviews, photo vignettes, live-action news footage and everyday images of Koreatown, Los Angeles. The L.A. Riots are largely conceived of as being a local event, something that was particular to Los Angeles and the race relations of this area. However, Sa-I-Gu introduces a transnational perspective through which a public audience can come to understand the socioeconomic politics behind the riots, rather than the usual domestic perspective that was offered in May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE a majority of other mainstream media outlets at that time. It also raises questions regarding the politics of media representation and who has power over such representation. Where do these alternative perspectives (regarding transnationalism and representation) have the opportunity to be voiced or screened, and under what circumstances? The film, Sa-I-Gu, further provides a glimpse into the otherwise hidden perspectives of women in the Korean-American community three months after the riots. Produced by Christine Choy, Elaine Kim, and Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, this live-action documentary was released in 1993, a year after the riots, and broadcast nationally on PBS' "Point of View" series. The Korean American women presented in the film owned and worked in some of the many businesses that were destroyed during the violence of the riots (approximately half of the $850 million in losses during the riots were suffered by Koreans). These women and their multi-dimensional interviews reveal the inherent transnational nature of their lives and the L.A. Riots, producing a documentary that can thus be considered transnational and intercultural cinema. In a similar vein as other intercultural cinema, Sa-I-Gu performs a double movement of “tearing away old, oppressive representations and making room for new ones to emerge.” Before the film begins, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson states that the goal in producing Sa-I-Gu was to “give voice to the voiceless,” clarifying that she is referring to the Korean American shop owners and keepers who lost everything during the upheaval. One way in which the producers gave voice to these women was through the use of their personal photographs. The use of these photographs play a large part in conveying the transnational nature of these women’s lives and their perspectives of life in America before and after the riots. May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE Many of the individual interviews were supplemented with a slideshow of images of each woman, before and after immigration to the States, thus representing them within their own stories as subjects rather than mere objects of history. Audiences are subsequently able to see these women beyond the label of “victim,” beyond the representations they have seen in mainstream news media and recognize the transnational context in which these women have come to understand their own experiences in light of the riots. The photographs include pictures of the women and their husbands on their wedding days, set in Korea, with western-style wedding dresses and suits; on vacations in the United States with famous landmarks such as the Golden Gate Bridge, Grand Canyon or skiing in the mountains; and later pictures with their children in America, celebrating holidays in both Western-style clothing and han-boks (Korean traditional dress). They exemplify the complexity of these women’s lives and stories and introduce viewers to representations of these women that move beyond the simplistic lens of a “Black-Korean conflict” that culminated in the riots. Elaine Kim notes that the images in the photographs (and more broadly, in Sa-I-Gu) are in direct contrast to the three most popular images of Korean Americans that were circulating in mainstream news media immediately before, during, and after the riots: a female Korean shopkeeper shooting a Black teenager, Latasha Harlins, in the back of the head (this was actually the second most widely shown video during the week after the riots); hysterical, begging, crying, and inarticulate female Korean shopowners/victims with heavy accents that evidenced their foreigner status; and male Korean merchants on rooftops brandishing large guns, apparently valuing money and property over human life, and ready to shoot any looters or trespassers. The use of family pictures from Korea and their early days of immigration to America provide a more personal and identifiable representation of the women while supporting their May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE stories about coming to America in order to discover the American Dream for themselves and their families. Viewers are then invited to explore how this American Dream was shattered on April 29, 1992 (literally translated Sa-I-Gu, 4-2-9, in Korean) through the use of live-action news footage and newspaper photographs of scenes of smoke clouds, burning buildings, looters and stationary police officers during the riots. While the juxtaposition of these stories and images create a sense of inequality, injustice and unfulfilled hopes and dreams, it is completed in a way that does not place blame on any of the usual suspects. In both Korean and English, the women emotionally and eloquently articulate the way in which their life work and savings were destroyed in a few days, during which time little assistance was provided from the police and government. As stated above, these interviews offer images of Korean American women that are in direct contrast to other representations that were available in mainstream media at the time. The women are able to clearly and touchingly express their thoughts and feelings in a way that any viewer would be able to relate to, regardless of race or gender. They are not simply angry or sad; they are thoughtful in their analysis of the riots, the cause, and their proposed solution. Many of the interviewees point to the misrepresentations in media and their tendency to wrongfully frame a Black-Korean conflict as the cause of the riots, rather than a symptom. As admitted by Young Soon Han (Mrs. Han), an owner of a liquor store that was destroyed in the riots, she did not know “to whom to be angry” – the rioters, herself, the police, or even the entire country. In the end, she simply states that she was “totally confused.” Mrs. Han is one of the three women who were interviewed in-depth throughout the film. While the film offers short interviews with over fifteen women, we only learn the names and detailed life-stories of three women: Young Soon Han, a storeowner; Choon An Song, a family May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE market owner; and Jung Hui Lee, a clothing store assistant. Mrs. Han speaks primarily in English as she explains how she came to be the owner of a liquor store and how it was destroyed in the riots. Beginning with the touching love story of how she met her husband during middle school in Korea, she chronicles their immigration to America after their marriage in 1970. She first worked as a registered nurse, while he later worked at the liquor store, which they purchased with fifteen years of savings and additional bank loans. She emotionally shares that her husband became gravely ill, and that after his death, she had to take over the liquor store, which was extremely difficult for her because she was not a business woman and was not accustomed to handling money. Mrs. Han astutely recognizes the transnational ties of the riots and relays the sentiments of many of her Black customers, who clearly also see transnational threads in their own understandings of the riots. She quotes them as saying, “In general we feel sorry, but we couldn’t help it because many Koreans don’t try to understand Black people… Koreans are brainwashed by white people especially because they are already educated by them in Korea.” She understands the logic behind this reasoning, but still argues that the riots were unfair because she regards it as all of the anger that the Black community had towards White people, accumulated and expressed to Koreans. Choon An Song has a similar take on the riots in that she felt betrayed by the Black community, but she follows this statement with a plea that Koreans should treat the children of the Black community as their own, since “we are all God’s children.” As a devout Christian, she states that she does not regret coming to America, even after the riots, because her children have done well here and her husband came to accept Christ here. Even as she expresses her shattered May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE dreams of America and the ideal it did not live up to for her, she has a smile on her face and tells viewers that her customers nicknamed her “Smile” because she was always happy to serve them, and even on holidays, she and her husband would throw parties for the neighborhood and prepare wrapped gifts for them. Mrs. Song’s two sons, who were also interviewed for the film, state that their parents gave up everything in Korea to come here in hopes of providing a better educational future for their children. They reason that in Korea their mother would never have had to work, but rather had maids because their father was the boss of a large business. While they understand that their parents would have led a more comfortable life in Korea, they also acknowledge that Korea was not their home. In fact, they identify so much as Americans that one of the sons identifies himself as an officer, meaning he is an officer in the United States military. We are simultaneously shown pictures of him in uniform with other soldiers and officers of various races. As an officer, he is mostly upset at the government, law enforcement and National Guard troops that were sent into L.A. to “protect” the community. He retells the story of how he called the police once the riots broke out, but that the snide response he received was, “I hope you have good insurance, because we aren’t going out there.” Even with the deployment of the National Guard, he saw that it was not enough the help the business owners, especially since he saw them only stationing themselves in Japan Town to protect the higher income areas of Beverly Hills. In fact, during the riots, Mayor Tom Bradley closed schools and businesses and implemented a citywide curfew. Nonetheless, the situation became so horrible that Governor Pete Wilson was forced to dispatch 4,000 National Guard troops to patrol the streets and prevent rioting (in total, there were more than 30,000 law officials stationed in the area, with most protecting the surrounding middle-upper class residential areas). All across the country, people watched the May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE events unfold: the city was plagued by fire, businesses were robbed and destroyed by looters, and innocent bystanders were injured or killed. Actual footage is shown of LAPD officers standing by their patrol car, drinking water watching looters are seen taking merchandise out of nearby shops and starting fires to others. Yet, of these three main women, much of the film revolves around the interviews of Mrs. Jung Hui Lee and news media coverage, newspaper reports and scenes from the death and funeral of her eighteen-year-old son, Edward Jae Song Lee – the only Korean fatality of the fiftyfour deaths during the riots. In fact, Sa-I-Gu is dedicated to “Edward Jae Song Lee and the fiftythree sons and daughters who died during Sa-I-Gu.” The film begins with a scene of Mrs. Lee sitting in a chair, alone in a room in her home, with a large picture of her son, Edward, hanging on the wall behind her. She later states that she often expects him to come home and feels as though she is waiting for his return because she cannot believe that he is gone. He left without saying goodbye, and she feels that “he was sacrificed” in the riots, because he was not willing to stay home and watch as the Korean American community’s life savings were looted and burned down. Viewers learn that Edward was actually shot by another Korean who mistook him for a looter. As Mrs. Lee recounts bits and pieces of the story of how her son became a victim of the riots, scenes from his large funeral create a montage of images of the Korean American community mourning, coming together and supporting each other during this difficult time. The funeral service was held at a baseball park, with the pastor speaking from the head of the diamond at home base. As the camera pans the attending crowd, viewers see how it stretches out to the fences that enclose the park, with people sitting in chairs, on the grass, and even standing. May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE It is easy to see that not everyone attending is an immediate family member or friend, but rather members of the community who wished to support the Lee family at this time. Many hold up signs with messages of sympathy and solace written in both Korean and English. The camera zooms in on one in particular before moving on, In Loving Memory Edward Song Lee We grieve together as One family for the Loss of our brave son (emphasis theirs) Mrs. Lee begins her interview by telling the viewers that she and her husband came to America, “…to spread our young dreams and to raise our future children…we were young and our dreams small, but we came here with dreams.” They arrived in the states in April 1972, Edward was born a little over a year later in May 1973, and twenty years after their arrival, Edward lost his life in the L.A. riots – tragically shattering their small dreams. Mrs. Lee exclaims, “Something is drastically wrong,” when discussing the discrepancy between transnational imaginations of America and the nation and the realities of life, work and opportunity here. She remembers how long she had to work as a cleaning lady for office buildings in the evenings and the way that a Jr. High aged Edward would come to help her vacuum. With tears, she shares that her chest feels tight whenever she thinks of those times that he should have been playing with friends, but instead had to help her with work. Mrs. Lee bears May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE that it wasn’t an individual who shot her son, rather the LAPD did not act soon enough and the National Guard was nowhere to be seen. She feels it necessary to think about it more broadly and see that it was not an individual – not an individual matter – but a symptom of larger, drastic injustices. This interview acts as a voice over narrative to a succession of Lee family pictures. They include a picture of Edward as an infant dressed in a Korean traditional han-bok (most likely for his dol, or first birthday celebration) with his father holding him, dressed in a suit. They end with a picture of a teenaged Edward dressed in jeans and a sweatshirt, hugging his mother, who is dressed in a han-bok. These images lend to the intercultural nature of the stories in particular and this film in general. As noted by Laura Marks in, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment and the Senses, the term intercultural “indicates a context that cannot be confined to a single culture” but one that “suggests movement between one culture and another, thus implying… the possibility of transformation.” Indeed the photos and interviews conducted in Sa-I-Gu reveal the transformed notions that these women had of America and the American Dream. However, they also reveal the transformation these women experienced in their own perceptions of their identity in relation to the nation of America. Whereas once they were simply regarded as foreigners or immigrants, after the riots, their stake in this country and demands for rights and reparations clearly marked a turning point in Korean American identification. Many of the additional women who were interviewed also exemplify these transformed ideologies and identities. One interviewee states that to her Mi-Gook (“America” in Korean) meant “beautiful country” but that she now sees it as Mi-Chin Na-Ra, or “Crazy Country” with all of her original feelings about it having been turned upside down after experiencing the May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE injustice of the riots and what led up to the riots. Several women agree, although interviewed separately, that they can understand why the riots happened because they also feel the Rodney King verdict was unjust and that the community must have been expressing their “accumulated contempt for the wrongful judgment.” One woman in particular, a store owner who worked seven days a week “with no life of (her) own” to find everything lost in one morning, expressed that if the government had “watched over the Black people better” that they would not have lashed out at the Koreans. Leaving her to be the “most angry at White people.” This short interview is coupled with footage of scenes from Beverly Hills, Hancock Park and other affluent areas of Los Angeles. The people in these scenes are all white, seen eating lunch in front of nice restaurants, shopping in boutiques or simply walking down nicely manicured sidewalks with children or shopping bags in tow. Obviously the juxtaposition of these images with those of the Koreatown and interviews are meant to alert viewers to the deep inequalities that structure not only the event of the riots, but everyday life in America. In fact, Mrs. Song pointed out that before arriving in America, she had expected that Beverly Hills image of what she had seen in Hollywood movies, clean streets with flowers in window sills, palm trees, and endless blue skies. Instead, she was greeted with pollution, poverty, crime, and the complete absence of white people. Her experience in America reveals the deep rift that exists in our nation, the division among class and race. Mrs. Song notes that she felt she was in Mexico rather than America, because she never even had the chance to come in contact with a white person. She didn’t know where they lived or worked. Other interviewees go further to reason that the riots broke out as a result of the widening gap between the rich and poor communities in this area of Los Angeles. One woman, filmed in her apartment, shares that she had to hide during the riots and aid never came. Even when May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE helicopters flew by overhead, they did not notice her waving for help, so she lost all hope. It was at this time that she realized that all of the looters were poor and that the riots were happening because of a gap between the rich and the poor. While the media denies a Black/White conflict and uses Koreans as “sacrificial lambs” she feels that they wrongfully stress a Black/Korean conflict. This sense of being made to be a victim and scapegoat angered many Korean Americans and sparked a feeling of American national identity in that they finally had a reason to fight for their rights in this country. As taxpayers, hard working citizens and residents, they felt that if the government could not protect them during the riots, they should at the very least grant reparation for what they had lost. Thus, the Association of Korean American Victims was born. Several interviewed women were members of this association. Along with men and children in their community, they gathered daily to demonstrate through >marches and protests demanding reparation from the government, whom they felt stood by to watch rather than protect them during the riots. Their goal was to receive reparation but also to raise awareness regarding the injustices that had occurred to all ethnic and racial communities in Los Angeles during the riots. One of the most moving interviews is with an elderly grandmother who states that she demonstrates for reparation because when she saw the riots happening, she was brought to tears for her children and her children’s children. With a shaking voice and strong spirit she states that she is the most upset at the police who stood by as their buildings were burned and now only wishes that she could die demonstrating for the cause. It is interesting that Sa-I-Gu: From Korean Women’s Perspective was broadcast on PBS, but Wet Sand: Voices From L.A., the ten-year anniversary sequel, was not. With the Wet Sand sequel, director Dai Sil Kim Gibson hoped to provide, “A powerful chorus of voices that not all May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE is well in America, that there are deeply rooted flaws in American society, but there is hope to be realized. We have to struggle for it. The unrealized hope, America. I hope this will challenge them to think and act.” In a similar manner to Bush Mama, both films blur the lines between documentary and narrative film. As intercultural cinema, they are examples of the uses of alternative space to find alternative forms of expression. While Sa-I-Gu focused on providing a space for the voices of Korean American Women perspectives, Wet Sand delved further into several different perspectives from the various communities in South Los Angeles, which also led to its criticism for trying to do too much. I would argue that this might have attributed to why the sequel was not aired on PBS or Independent Lens, a series programmed by representatives of the Independent Television Service and PBS people. Wet Sand filmmaker Kim-Gibson was told, "We did not feel that your film is tightly focused around the kind of strong personal narrative that we are currently seeking for the series." Kim-Gibson states that she did not understand what this meant but was later informed that, "It means the film does not have a formula of beginning, middle, and ending with happy resolution." In the film, Kim-Gibson revisits Los Angeles to learn what changes have occurred since then, only to discover that living conditions have deteriorated and that few remedies have been administered to the communities most stricken. Through interviews with a multi-ethnic set of first-hand witnesses, this essential follow-up probes deeper into the racial and economic issues that not only shaped the climate of 1992 Los Angeles, but also continue to affect all Americans today. Ultimately, the film presents a controversial understanding of our present, “unrealized hope, America.” Unfortunately, Wet Sand exemplifies the difficulties intercultural cinema face in the areas of representation and distribution. While it proves to be a great source of alternative perspectives, representations and understanding, if it lacks the ability to reach an audience though a public May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE medium, the same issues of agency and authorship remain. Theses stories and perspectives become another addition to the many parts of America’s social fabric that have been buried in history and lost in memory. The remnants of the L.A. Riots that do remain in our collective imagination are often conflated with similarly vague memories of the Watts Rebellion of 1965 rather than being understood for the distinct elements that led to the 1992 Rebellion. In fact, during the filming of Wet Sand Kim-Gibson was surprised to encounter a whole generation of individuals who had no memory of the Riots and did not know how it had impacted their communities or current notions of race relations in Los Angeles. This is why Kim-Gibson decided to title the film, Wet Sand. She was inspired by a quote from Mrs. Lee (Edward’s mother) when interviewing her a decade after her son’s death. While discussing the politics of race relations in post-1992 riots Los Angeles, Mrs. Lee states, "Unity is like holding wet sand tightly in your hand. If you hold a fistful of wet sand, it becomes one big lump. But if the sand dries, it will slip out through your fingers until there is nothing left." The question then remains, how do we keep the sand wet? What medium is needed to maintain the unity and keep it from slipping? The film does not really provide an easy solution as to how unity might be achieved in order to foster positive race relations and “nationhood.” When we understand race and its function in our modern society, the question of whether unity is even achievable along racial lines begs our attention. Michael Omi and Howard Winant define race as a modern phenomenon and most importantly, a social construct as opposed to a biological assignment. Especially with the onset of imperialism and colonization, racial categories were used to create hierarchies to justify the conquering of other nations and peoples, along the lines of racial reasoning, that one race (namely the European American/ White race) was superior to others (colonized and enslaved May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE races/countries). These racial hierarchies also worked to pit minority races against each other and prevent them from organizing together against the “superior” races in power. In his book, A Different Mirror, Ronald Takaki does a great job of describing “alternative” American histories of marginalized perspectives and explaining how plantation owners eventually pit laborers of color against Irish laborers by incorporating the latter into whiteness and offering them higher pay rates, simply due to the color of their skin. This demonstrates the social constructed nature of race, but also hints to our present notions of race relations and racial understandings. The model minority myth has also been a symptom of the construction of racial identities and worked to create a hierarchy and animosity between Asian and Black communities in America. Coined in the mid-1960s by William Petersen, the term model minority has been used to describe Asian Americans as a model ethnic minority group that has been able to achieve high rates of assimilation and success (they apparently go hand in hand!), despite marginalization, due to innate characteristics of hard work ethic, family values, and self-sufficiency. The ability of Asian Americans to succeed in a capitalist economy, based on “merit” alone, was often particularly referenced against the experiences of African Americans who were depicted as relying on governmental services and “welfare-handouts.” Modelminority.com notes that: While superficially complimentary to Asian Americans, the real purpose and effect of this portrayal is to celebrate the status quo in race relations. First, by over-emphasizing Asian American success, it de-emphasizes the problems Asian Americans continue to face from racial discrimination in all areas of public and private life. Second, by misrepresenting Asian American success as proof that the US provides equal opportunities for those who conform and work hard, it excuses US society from careful scrutiny on issues of race in general, and on the persistence of racism against Asian Americans in particular. The problematic nature of the model minority myth is obviously not mere theoretical concern but lived reality that is recognized within the interviews of the Korean American women May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE in Sa-I-Gu. Although they do not used the exact term “model minority,” they see the incongruity between their lived reality and the stereotypical representations of America and their place in the American Dream. They communicate a deep comprehension of the creation of race relations and racial hierarchies and their role as a sacrificial lamb or scapegoat within that equation. Several women explain that the riots are simply one illustration of how racial dynamics and institutions in Los Angeles go beyond a black/yellow dichotomy – because their experience as immigrants and transnational communities cannot be compared to that of Blacks in America, who were brought here as slaves and suffered centuries of oppression in the States. These women perceptively identify that Sa-I-Gu was more than a race riot concerning just the Black and Korean communities, it is evidence of deeper structural issues and inequalities in the United States: issues that have found a place to begin to be explored within intercultural cinema, such as Sa-I-Gu and Wet Sand. In closing, I would like to caution viewers to the dangers of essentializing when trying to represent people as subjects when they are commonly depicted as “other.” If such alternative images are only available in scarcity, many viewers see it as speaking for the whole. Thus, some viewers may watch Sa-I-Gu and feel that these women interviewees are representing the voices of all Korean American women in Los Angeles. Fortunately, the film begins with the significant note that these women who are interviewed are “speaking only for themselves” and that is how they wish to be heard. Still, my hope is that these few voices (while resisting notions of essentialism) can help us to change the way in which we have been trained to see and understand race, race relations and the American Dream in light of the 1992 Los Angeles Riots. May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE **Here is an example of another form of alternative space for alternative perspectives/voices. Ishle Park is a well-renowned Korean American spoken word artist and this is one her more well-known pieces. I don’t have the room to analyze it here, but wanted to share it with you.** SA-I-GU By Ishle Yi Park koreans mark disaster with numbers. April 29, 1992. fire. if I touch the screen my fingers will singe or sing. * we watch grainy reels of a black man flopping on concrete arched, kicked, and nightsticked, rodney king. here I rub my own tender wrists, ask my mother unanswerable questions why are the cops doing this? my mother will answer simply, and wisely, because those cops are bad. May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE of the looters, because they are mad. But why hurt us - she chokes Because, Ishle, we live close enough. While l.a.p.d. ring beverly hills like a moat, They won't answer rings from south central furious and consistent as rain. where did they hide, our women under what oil-stained= chevy did they breathe life? who pulled them by hair into riot for a crime they did not commit who watched and did nothing? * the mile high cameras hover, they zoom in, dub it: war of blacks & koreans then watch us rip each other to red tendons for scraps in the city that they abandoned, a silence white as white silence and we have no jesse May 2008 v1 no1 CULTURE CRITIQUE no martin no malcolm no al, no eloquent, rapid tongue just fathers, with thick-tongues and children, too young to carry more than straw broomstick and hefty bag. all the women cry and they hurl what is not already shattered. * but two mornings later, they march over ashes dust licking their proud ankles 30,000 koreans sing in a language that most will never master a tribute song to those who came before and those who will march after we shall overcome someday. copyright © 2008 culture critique Cultural Studies Department: School of Arts & Humanities Claremont Graduate University 121 East Tenth Street, Claremont CA 91711